Maps are weirdly deceptive. We look at a map of the us and mexico border and see a crisp, thin black line separating two massive nations. It looks permanent. It looks simple. But if you actually stand on the dirt in Nogales or Eagle Pass, that line starts to feel a lot more like a suggestion than a geometric certainty.

The border stretches nearly 2,000 miles. 1,954 miles, to be exact, if you’re counting the way the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) does. It cuts through shifting river sediment, sun-baked deserts, and backyard fences.

Most people think they understand the geography because they’ve seen the political maps on the news. They haven't. Honestly, the real map is a mess of jurisdictional nightmares and historical accidents that date back to 1848.

The Rio Grande is a Terrible Border

Geography 101 says rivers make great borders. Geography 101 is wrong.

The eastern half of any map of the us and mexico border is defined by the Rio Grande, or the Río Bravo as they call it south of the line. Rivers move. They meander. They flood. Back in the 19th century, the river decided to pull a fast one near El Paso, shifting its course and creating a 600-acre chunk of land known as the Chamizal.

For decades, the US and Mexico argued over who owned that dirt. It wasn't until 1963 that LBJ and Adolfo López Mateos finally settled it by literally cementing the river into a man-made channel. We forced the map to behave.

But you can't cement 1,200 miles of river. Today, when the Rio Grande shifts, it creates "bancos"—small pockets of land that technically swap sides. It makes the map of the us and mexico border a living, breathing document that changes every time there's a heavy monsoon season.

📖 Related: King Five Breaking News: What You Missed in Seattle This Week

If you're looking at a static map, you're looking at a snapshot of a moment that has already passed.

The Concrete Jungles of the Borderlands

Then there are the "Twin Cities." You've got San Diego and Tijuana. El Paso and Juárez. Laredo and Nuevo Laredo. On a map, these look like distinct spots. On the ground? They are one giant, pulsing metropolitan organism.

The map of the us and mexico border here is basically a collection of bridges. Take the Gateway to the Americas International Bridge. Thousands of people cross it every single day just to go to work or buy groceries. For the people living there, the map isn't a wall; it's a commute.

The Empty Spaces: Where Maps Fail

West of El Paso, the river ends. The border becomes a series of straight lines drawn by surveyors who were probably exhausted and dehydrated in the 1850s. This is the High Desert.

This part of the map of the us and mexico border crosses the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts. It's brutal. When you look at a digital map of this area, you'll see vast stretches of nothingness. No roads. No towns. Just a line cutting through the cactus.

- The Tohono O'odham Nation: This is a major complication that most casual map-readers miss. Their ancestral lands are split right down the middle by the international line.

- Monuments: There are 276 physical markers—obelisks, really—that define the overland boundary from El Paso to the Pacific.

- The Pacific Termination: The border doesn't just stop at the beach; it extends into the ocean, which is a whole different jurisdictional headache for the Coast Guard and the Mexican Navy.

The terrain is so rugged that "the line" is often just a row of steel bollards or, in some places, absolutely nothing but a rusted barbed-wire fence that a cow could knock over.

👉 See also: Kaitlin Marie Armstrong: Why That 2022 Search Trend Still Haunts the News

Why Scale Matters When You Look at the Map

If you zoom out, the border looks like a scar. Zoom in, and it's a patchwork.

There's this thing called the "100-mile border zone." The US government claims extra authority within 100 miles of the line. If you live in San Antonio, Tucson, or San Diego, you are technically on the map of the us and mexico border in the eyes of federal law. That’s roughly 200 million people living in a legal gray area where Fourth Amendment protections against search and seizure are... well, they're complicated.

Practical Realities for Travelers and Researchers

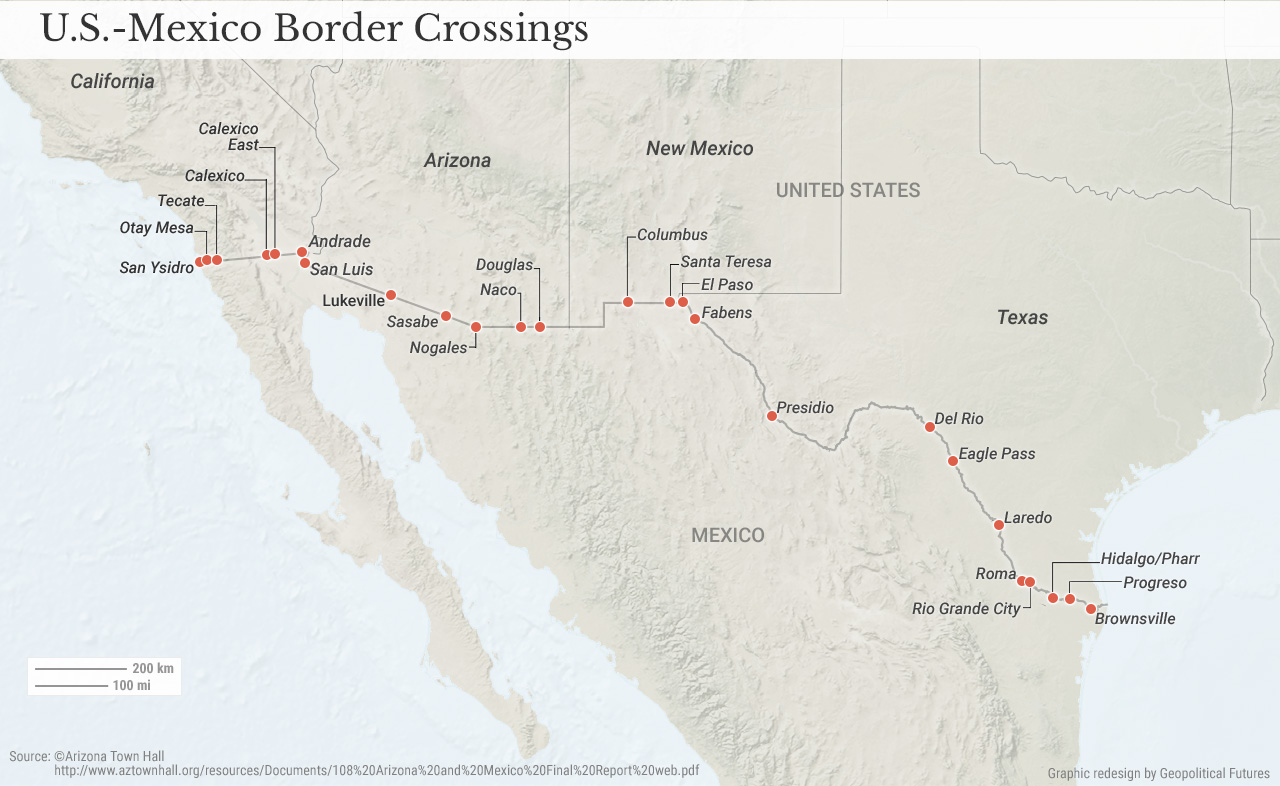

If you are actually trying to use a map of the us and mexico border for travel or logistics, stop looking at the line and start looking at the Ports of Entry (POE).

There are about 48 of them.

Each one has its own personality. San Ysidro is the busiest land border crossing in the world. It’s a chaotic symphony of idling engines and street vendors selling churros. Then you have places like Boquillas in Big Bend National Park. There, the "map" involves a rowboat and a park ranger who checks your passport after you cross a river that’s barely knee-deep.

Data Sources You Should Actually Trust

Don't just trust a random image search. If you need the real data, go to the source.

✨ Don't miss: Jersey City Shooting Today: What Really Happened on the Ground

- The IBWC (International Boundary and Water Commission): They are the keepers of the official coordinates.

- US Census Bureau (TIGER/Line files): Great for GIS nerds who want to map the actual human density along the line.

- INEGI (Mexico’s equivalent): To get the perspective from the southern side.

The Infrastructure Overlay

A modern map of the us and mexico border isn't just dirt and water. It’s technology. It's "virtual walls."

There are autonomous surveillance towers (ASTs) that use AI to distinguish between a cow and a human from miles away. There are underground sensors. There are drones. When we talk about the map today, we’re talking about a digital grid as much as a physical one.

This creates a weird "filter" over the physical geography. The map tells the Border Patrol where to look, but the terrain—the arroyos and the hidden canyons—tells people where to hide. It's a constant game of topographic chess.

Actionable Insights for Using Border Maps

If you're planning to visit the border region or researching the area, keep these specific points in mind to avoid getting lost or ending up in a restricted zone:

- Download Offline Maps: Cell service is non-existent in the desert stretches of the Arizona-Sonora border. If you rely on live Google Maps, you will get stranded. Use Gaia GPS or OnX if you're going off-road.

- Check Port Wait Times: Use the CBP "Border Wait Times" app. A map might show you the shortest distance, but it won't tell you that the Bridge of the Americas has a three-hour delay while the Stanton Street bridge is empty.

- Respect Private Property: In Texas, the border is almost entirely private land. Just because a map of the us and mexico border shows a river bank doesn't mean you have the right to walk on it. You'll run into angry ranchers long before you run into federal agents.

- Know the Checkpoints: Internal checkpoints are often 20 to 50 miles away from the actual border. If you’re driving north, expect to stop. This isn't on most tourist maps, but it's a huge part of the geographical reality.

The border isn't a static thing. It's a process. It’s an ongoing negotiation between two countries, a temperamental river, and the millions of people who call that line home.

Stop thinking of the map of the us and mexico border as a line in a textbook. Start thinking of it as a 2,000-mile long conversation that never ends. If you want to understand the US, you have to understand where it ends and where something else begins. And usually, that transition is a lot blurrier than the map-makers want you to believe.

To get the most accurate visual representation, always cross-reference satellite imagery with official IBWC boundary data rather than relying on standard street maps, which often fail to account for recent river diversions or updated fencing locations. Check the current status of "bollard" vs "pedestrian" fencing if you are conducting site-specific research, as these distinctions radically change the physical accessibility of the terrain.