He had a glass of bourbon and water. He paid his bill. Then, Dan Cooper—we call him D.B. now because of a wire service typo—jumped out of a Boeing 727 into a freezing November rainstorm with $200,000 strapped to his torso. He vanished.

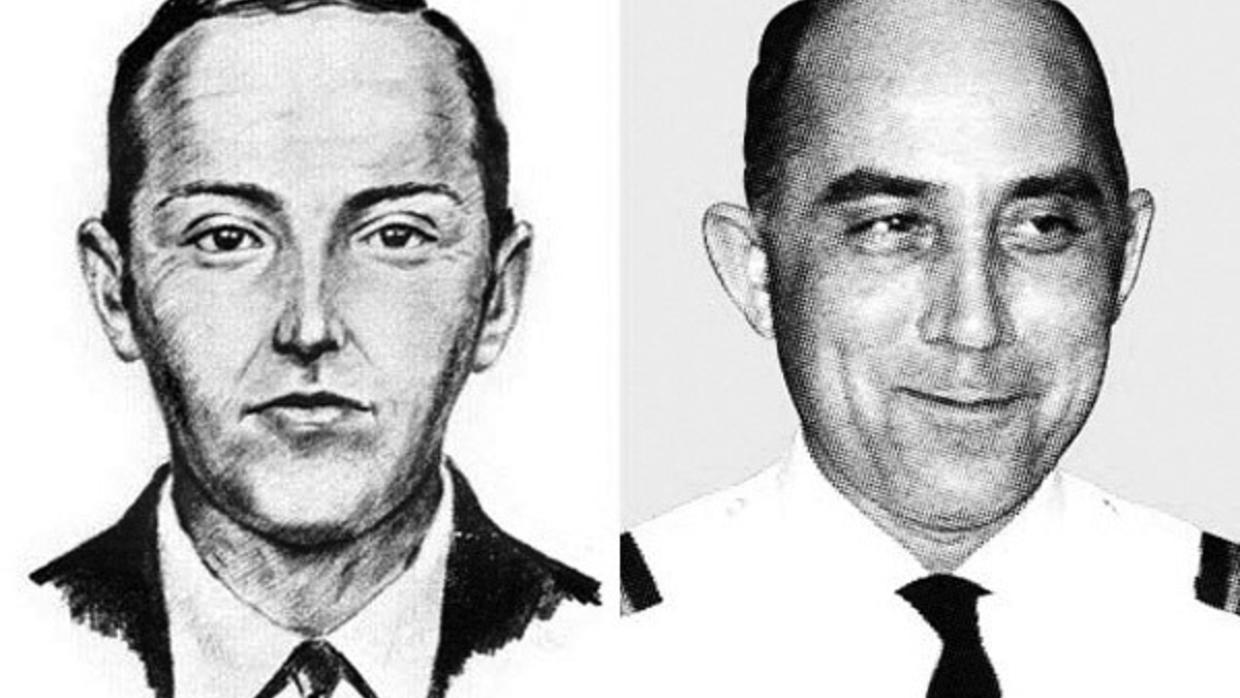

The mystery is legendary, but the DB Cooper sketch is the only thing we actually have to look at. It’s that famous composite of a stone-faced man in dark wrap-around shades and a narrow tie. You’ve seen it on t-shirts, posters, and History Channel specials. But here’s the thing: that drawing might be the very reason the FBI’s largest manhunt ended in a giant pile of nothing.

Composite sketches are notoriously flaky. They rely on the adrenaline-spiked memories of people who were, frankly, terrified. When you look at the primary DB Cooper sketch, you aren't looking at a photograph. You’re looking at a game of telephone played between a sketch artist and three flight attendants who were trying to stay calm while a man threatened to blow up a plane with a briefcase full of red sticks and wires.

The Problem With the Most Famous Face in True Crime

Most people don't realize there isn't just one DB Cooper sketch. There are several versions, and they don't exactly agree with each other. The most iconic one, often referred to as "Composite B," was created by FBI artist Roy Rose. It shows a man who looks to be in his mid-40s with a receding hairline and a very distinct, almost hollow-cheeked expression.

Think about the environment. The lighting in a 1971 aircraft cabin wasn't great. It was dim. The witnesses—Florence Schaffner and Tina Mucklow—were under immense pressure. While Cooper was described as "calm" and "not nervous," the situation was the opposite of relaxed.

When the FBI released the first DB Cooper sketch, it was a rougher, more primitive version. Later, they refined it based on more detailed interviews. But by then, the image was burned into the public consciousness. If the "real" Cooper had a slightly different nose or a rounder jaw, he could have walked past a "Wanted" poster of himself and nobody would have blinked.

Humans are bad at faces. Honestly, we’re terrible at it. Research from experts like Dr. Elizabeth Loftus has shown that eyewitness testimony is one of the least reliable forms of evidence. In the Cooper case, the sketch became the "truth," even if it was just a filtered interpretation of a memory.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

Why Composite B Is So Polarizing

Check out the shades. In the most famous DB Cooper sketch, the suspect is wearing dark sunglasses. This is a huge hurdle for investigators. The eyes are the most defining feature of a human face. By covering them, the sketch loses the very thing that helps us differentiate one middle-aged white guy from another.

The FBI later produced a version without the glasses, but it felt like guesswork. They had to "invent" the eyes based on what the flight attendants caught in brief glimpses when Cooper took the glasses off.

Some researchers, like Eric Ulis, who has spent years chasing this case, argue that the sketches might have led the public away from the real culprit. If the sketch was even 10% off, it would exclude thousands of potential suspects who actually fit the physical profile.

The Tie and the DNA That Changed the Game

While the DB Cooper sketch gets all the glory, the real breakthroughs in recent years haven't come from looking at his face. They’ve come from his clothes. Cooper left his clip-on tie behind on seat 18-E.

That tie is a goldmine.

In 2011, paleontologist Tom Kaye and his team used electron microscopes to find particles on the tie. They found bits of pure titanium and rare earth elements like cerium and strontium. In 1971, these weren't common materials. You didn't just find titanium dust at a grocery store. This suggests Cooper worked in a very specific industrial environment—likely a chemical plant or a specialized aerospace facility like Boeing or Tektronix.

🔗 Read more: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

This is where the DB Cooper sketch starts to fail us. If we are looking for a guy who looks exactly like the drawing, we might be ignoring a guy who looks 80% like the drawing but works at a titanium processing plant.

The FBI officially closed the case, known as NORJAK, in 2016. They didn't do it because they solved it; they did it because they ran out of leads. They decided the resources were better spent on newer, solvable crimes. But the "citizen sleuths" haven't stopped.

Comparing the Sketch to the Top Suspects

If you line up the DB Cooper sketch against the usual suspects, the results are... messy.

- Richard McCoy Jr.: He pulled off an almost identical hijacking less than a year later. He looked a bit like the sketch, but the flight attendants insisted he wasn't the guy.

- Robert Rackstraw: A former Army paratrooper with a wild past. When you put his 1970s photos next to the sketch, the resemblance is eerie. Even Rackstraw himself used to play into the mystery, though he never confessed.

- Sheridan Peterson: A colorful character who worked at Boeing and was an avid skydiver. He had the right build and the right hairline.

- Kenny Christiansen: A former paratrooper and Northwest Orient flight purser. His brother was convinced it was him, but Kenny was a bit shorter and thinner than the man described by the crew.

The problem is "confirmation bias." If you want Rackstraw to be Cooper, you’ll look at the DB Cooper sketch and see Rackstraw. If you think it was Peterson, you’ll focus on the ears or the forehead of the drawing and find similarities. We see what we want to see in the charcoal lines.

The Mystery of the "Missing" Features

There’s a detail in the original FBI descriptions that often gets lost. The witnesses mentioned Cooper had "swarthy" skin. This could mean he had a tan, or it could mean he had a slightly darker complexion, perhaps Mediterranean or even Native American heritage.

Yet, the most common DB Cooper sketch looks like a very standard, Caucasian businessman.

💡 You might also like: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

If the sketch leaned too hard into a "generic" look, the real Cooper could have been much more distinct. We also have to consider the "Bing Crosby" factor. One witness said he looked like the famous singer. Another said he looked like a mid-level executive. These are cultural touchstones, not precise measurements.

Why the Sketch Still Matters Today

Even if it’s inaccurate, the DB Cooper sketch is the anchor of the mystery. It represents the last time an American folk hero—if you can call a hijacker that—stepped out of the shadows and into the sky.

It also serves as a cautionary tale for modern forensics. Today, we have high-res CCTV and DNA profiling. In 1971, they had a sketchpad and a dream. The fact that we are still talking about this drawing fifty years later says more about our obsession with the "unsolved" than it does about the accuracy of the artist.

Actionable Steps for Deep Diving into the Case

If you're looking to go beyond the drawing and actually understand the mechanics of the NORJAK investigation, skip the fluff and look at the raw data.

- Review the FBI Vault: The FBI has declassified thousands of pages of the Cooper file. You can read the actual witness statements and see the evolution of the DB Cooper sketch from the first hours after the landing.

- Study the Flight Path: Cooper jumped over the "Victor 23" airway. Most researchers now believe he landed much further south than the initial search area, near the Washougal River in Washington.

- Analyze the Particle Data: Look up the reports from "Citizen Sleuths" led by Tom Kaye. The chemical analysis of the tie is much more reliable than any 50-year-old memory of a face.

- Visit the Washington State Historical Society: They occasionally hold exhibits featuring the few pieces of evidence that exist, including the instructions for the aft stairs Cooper used to jump.

The face in the sketch might be a ghost, but the titanium on the tie is real. Focus on the science, and the face might not even matter anymore.