Largo is tough. If you lived through October 2024, you know exactly what that means. When Largo Florida Hurricane Milton started churning in the Gulf, the vibe in Pinellas County shifted from "here we go again" to genuine, cold-sweat dread. We had just barely finished dragging water-logged drywall to the curb after Helene. Then Milton showed up.

It was a different beast.

Helene was about the water—that massive, heartbreaking surge that swallowed neighborhoods like Dana Shores and parts of Highpoint. But Milton? Milton brought the wind. It brought the rain that didn't seem to have an ending. For those of us hunkered down near East Bay Drive or along the Pinellas Trail, the sound of the transformer explosions was a rhythmic reminder that the lights weren't coming back on anytime soon.

The Reality of the Storm Path Through Largo

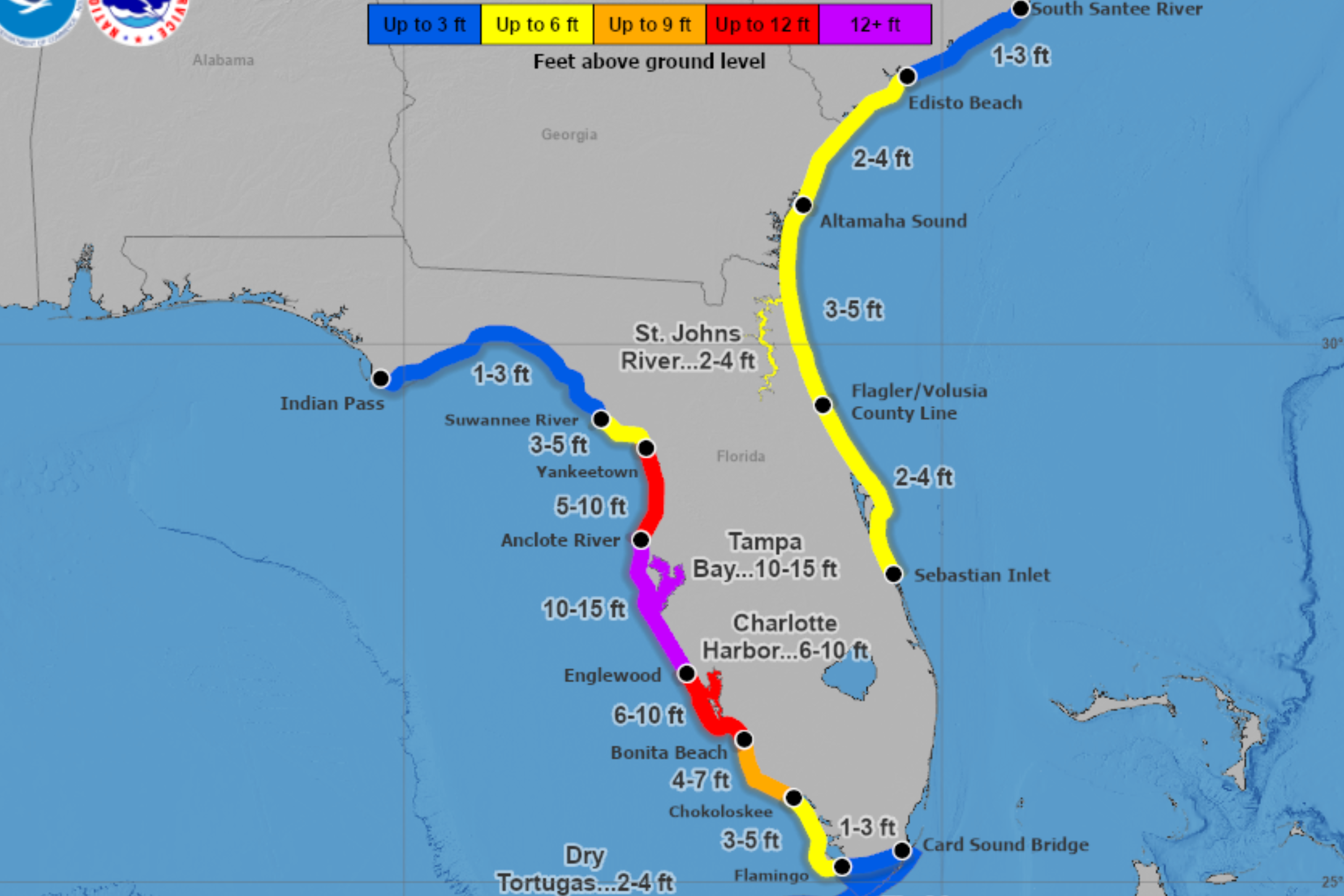

Everyone watches the "cone of uncertainty" like it’s a religious text. For days, the track for Milton wobbled. One update had it hitting Sarasota, the next it was a direct bullseye on the mouth of Tampa Bay. For Largo, being slightly inland from the Gulf beaches provided a false sense of security that Milton quickly dismantled.

The storm officially made landfall near Siesta Key as a Category 3. But don't let the "3" fool you. Because Largo was on the northern side of the eye—the "dirty side"—the wind gusts were punishing. We aren't just talking about a few shingles flying off. We are talking about massive oaks, trees that had stood since the 1970s, uprooting and crushing carports in mobile home parks like Japanese Gardens and Honeyvine.

Rainfall totals were staggering. Some pockets of Pinellas saw over 14 inches of rain in a single night. Largo’s drainage systems, already taxed by the wettest autumn in recent memory, simply couldn't keep up. Roosevelt Boulevard became a river.

Why the Wind Felt Different This Time

The pressure dropped so fast it made your ears pop. That’s a real thing.

When the wind speeds picked up in the middle of the night, it wasn't a constant whistle. It was a roar. It sounded like a freight train idling in your backyard. Experts from the National Hurricane Center later confirmed that Milton’s structure allowed it to maintain hurricane-force winds far inland. Because Largo is situated on the "Pinellas Peninsula," there is very little geography to break that wind down.

- Roof damage wasn't just about the age of the shingles. It was about the "lifting" effect.

- Many homes built after the 2002 building code changes held up remarkably well.

- Older structures, particularly those with gravel-and-tar roofs or unreinforced gables, saw significant failures.

The Power Outage Crisis and the "Dark Days"

If you want to talk about the real impact of Largo Florida Hurricane Milton, you have to talk about Duke Energy. At the peak, nearly 400,000 people in Pinellas County were in the dark. In Largo, it felt like 99%.

It wasn't just about the lack of AC, though in 90-degree Florida humidity, that’s a health crisis. It was the silence. No streetlights. No gas stations. No grocery stores. The Publix on West Bay Drive became a beacon of hope the moment their generators kicked in, with lines wrapping around the building just for bags of ice.

Wait times for power restoration stretched into a week for some neighborhoods. This created a secondary crisis: food spoilage. For families already struggling with inflation, losing $400 worth of groceries is a massive financial blow. Community centers like the Largo Public Library eventually became "cooling stations," proving that local infrastructure is about more than just books—it's a lifeline.

📖 Related: What Happens in an Earthquake: The Messy Reality of When the Ground Breaks

Misconceptions About Flood Zones in Largo

A lot of people think if they aren't in "Zone A," they are safe. Milton proved that's a dangerous myth.

While the storm surge from Milton ended up being less catastrophic for the Tampa Bay side than originally feared (due to the "negative surge" where the wind actually pushed water out of the bay), the freshwater flooding was insane.

Largo has a lot of low-lying pockets that aren't technically on the coast. Small creeks and drainage ponds overflowed. If you live near the Largo Central Park Nature Preserve, you saw how quickly "dry land" becomes a swamp. Many residents found themselves with six inches of water in their living rooms not because the Gulf rose, but because the sky fell.

Insurance companies are still processing the fallout from this. Many homeowners found out the hard way that their standard policy covers wind, but not the rising groundwater that seeped through their sliding glass doors. It’s a mess. Honestly, it’s a legal and financial nightmare that will take years to untangle.

The Economic Aftermath for Local Businesses

Walk down Ulmerton Road today and you still see the scars. Some signs are still bent. Some windows are still boarded up.

Small businesses in Largo took a one-two punch from Helene and Milton. When you lose power for six days, you lose your inventory. If you're a restaurant, you're done. If you're a hair salon, you can't work. For the mom-and-pop shops that make up the backbone of the Largo Chamber of Commerce, Milton was an existential threat.

- Labor Shortage: Contractors were spread so thin that getting a roof estimate took weeks.

- Supply Chain: Plywood and generators became more valuable than gold.

- Insurance Premiums: Expect them to skyrocket. Again.

Despite this, the "Florida Strong" sentiment wasn't just a bumper sticker. Neighbors were out with chainsaws before the rain even stopped. People were sharing generators and charging phones in their cars.

What the Data Says: Milton vs. Previous Storms

Comparison is how we make sense of the chaos.

When you look at Milton versus Ian (2022) or Irma (2017), the difference for Largo was the proximity of the eye. Irma was a giant that stayed mostly inland, causing widespread but often "minor" damage. Ian missed us and hit Fort Myers. Milton was the first time in a long time that the core of a major hurricane felt like it was sitting directly on top of Pinellas County.

The peak wind gust recorded at Albert Whitted Airport (just down the road in St. Pete) was over 100 mph. Largo likely saw similar numbers. That is enough to turn a lawn chair into a missile. It’s enough to peel the siding off a house like an orange.

The Trees

We have to talk about the trees. Largo is known for its beautiful canopy. But after Milton, the landscape changed. The city's debris removal teams worked 12-hour shifts for months. The sheer volume of vegetative debris—limbs, trunks, leaves—was enough to fill football stadiums.

📖 Related: Florida Race for Governor Explained: What Most People Get Wrong

This isn't just an aesthetic issue. Losing that canopy increases the "urban heat island" effect. It means less shade and higher cooling bills next summer. It’s a long-term environmental cost that we are only just beginning to calculate.

How to Prepare for the Next One (Because There Will Be a Next One)

Living in Largo means accepting a certain amount of risk. But "acceptance" shouldn't mean "apathy." If Milton taught us anything, it’s that your plan from five years ago is probably obsolete.

First, look at your windows. If you're still using masking tape, stop. It does nothing. Impact-resistant windows are the gold standard, but if those aren't in the budget, permanent hurricane shutter tracks are a must. Fumbling with heavy plywood while the wind is picking up is a recipe for an ER visit.

Second, the "battery revolution" is real. Gas generators are great until the gas stations run out of fuel or the lines are four hours long. Portable power stations (like those from EcoFlow or Jackery) can at least keep your fans running and your phones charged. They are quiet, safe to use indoors, and can be recharged via solar panels.

Third, check your "Loss Assessment" coverage on your insurance. If you live in a condo or an HOA, and the association has to repair a common roof or pool, they can pass that cost to you. This coverage is usually cheap—maybe $20 a year—but it can save you thousands.

Practical Steps for Largo Residents Post-Milton

If you are still dealing with the fallout or just want to be ready for the next season, here is the move:

✨ Don't miss: The Montgomery County Boil Water Advisory: What You Need to Do Right Now

Document Everything (Even Now)

If you still have soft spots in your ceiling or a fence that’s leaning, take photos today. Use a high-resolution camera and get multiple angles. Insurance adjusters are overwhelmed, and having a "timeline" of photos can be the difference between a claim being denied or approved.

Review Your Elevation Certificate

Even if you aren't in a high-risk flood zone, knowing your home's exact elevation relative to sea level is vital. You can usually find this through the Pinellas County Property Appraiser's website or by hiring a surveyor. If you’re just a few inches above the "base flood elevation," you might want to invest in sandbags or hydrabarriers before June hits.

Tree Maintenance

Don't wait for a storm warning to trim your oaks. Dead limbs are "widow-makers." Hiring a licensed arborist now—when they aren't in "emergency mode"—will cost less and likely save your roof.

Upgrade Your "Go-Bag"

The old advice was "three days of supplies." Milton showed us that ten days is more realistic. You need shelf-stable protein, at least one gallon of water per person per day, and a physical map of the area. When the towers go down, your GPS won't save you.

Largo is a resilient community. We saw it in the way people cleared the Pinellas Trail so bikers could get around. We saw it in the local churches that turned their parking lots into food distribution hubs. Milton was a brutal teacher, but the lessons are clear: respect the wind, prepare for the water, and don't count on the lights staying on.

We rebuild because this is home. But next time, we'll be ready.