You’re sitting there, maybe scrolling on your phone or finishing a coffee, and then the floor just... stops being solid. It’s not like the movies where you get a ten-second warning with a dramatic orchestral swell. It’s usually a sharp jolt or a low, rhythmic thud that feels like a heavy truck just slammed into your house. That is the exact moment you realize you're experiencing what happens in an earthquake, and honestly, your brain spends the first three seconds just trying to catch up with your inner ear.

Most people think of earthquakes as the ground opening up like a giant mouth to swallow cars. That’s a myth. Real seismic events are much more about vibration, displacement, and the terrifying sound of a building's skeleton being pushed to its literal breaking point.

The First Five Seconds: The P-Wave Arrival

Before the heavy shaking starts, there’s a precursor. Earthquakes release energy in different "flavors" of waves. The first to arrive are the P-waves, or primary waves. These are compressional. They push and pull the ground in the same direction the wave is traveling. It feels like a vertical "thump" or a sudden rattle of the windows. If you have a dog, you might notice them bolt upright a split second before you feel anything. This is because P-waves travel fast—about 6 to 7 kilometers per second through the Earth's crust.

Then comes the S-wave. The secondary wave. These are the ones that do the damage. They move slower, but they are shear waves, meaning they move the ground up and down or side to side. It’s a violent, whipping motion. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the intensity of this shaking depends entirely on your distance from the epicenter and, more importantly, what kind of dirt you’re standing on.

Why Your Neighborhood Matters More Than the Epicenter

If you are standing on solid granite, you’re in luck. The rock is stiff; it transmits the energy quickly and moves on. But if you’re in a place like Mexico City or parts of the San Francisco Bay Area built on soft bay mud or old lakebeds, you’re in trouble. Soft soil acts like jelly in a bowl. It amplifies the seismic waves. This is a process called liquefaction. Basically, the shaking increases the water pressure between soil particles, turning solid ground into a liquid slurry. Buildings don't just fall over; they sink. In the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, entire houses in the Mission District tilted into the mud because the ground simply stopped being a solid.

📖 Related: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

What Happens in an Earthquake Inside Your House

Forget the ground for a second. Let's talk about your living room. When the S-waves hit, your house begins to resonate. Every building has a natural frequency—a specific speed at which it wants to sway. If the earthquake’s frequency matches your building’s frequency, you get resonance. The swaying gets bigger and bigger with every pulse.

- The Sound: It’s deafening. It’s not just the earth; it’s the studs in your walls screaming, the glass vibrating in the frames, and the literal roar of the crust shifting miles below you.

- Non-Structural Hazards: This is what actually hurts people. Most earthquake injuries in developed countries aren't from collapsing ceilings. They are from "flying" objects. Bookshelves that aren't bolted to the wall become projectiles. Kitchen cabinets fly open, launching ceramic plates like shrapnel.

- The Power: Usually, the lights flicker and die almost instantly. Transformers on poles explode—which looks like bright blue flashes called "earthquake lights"—and the grid shuts down to prevent fires.

The Science of the Snap

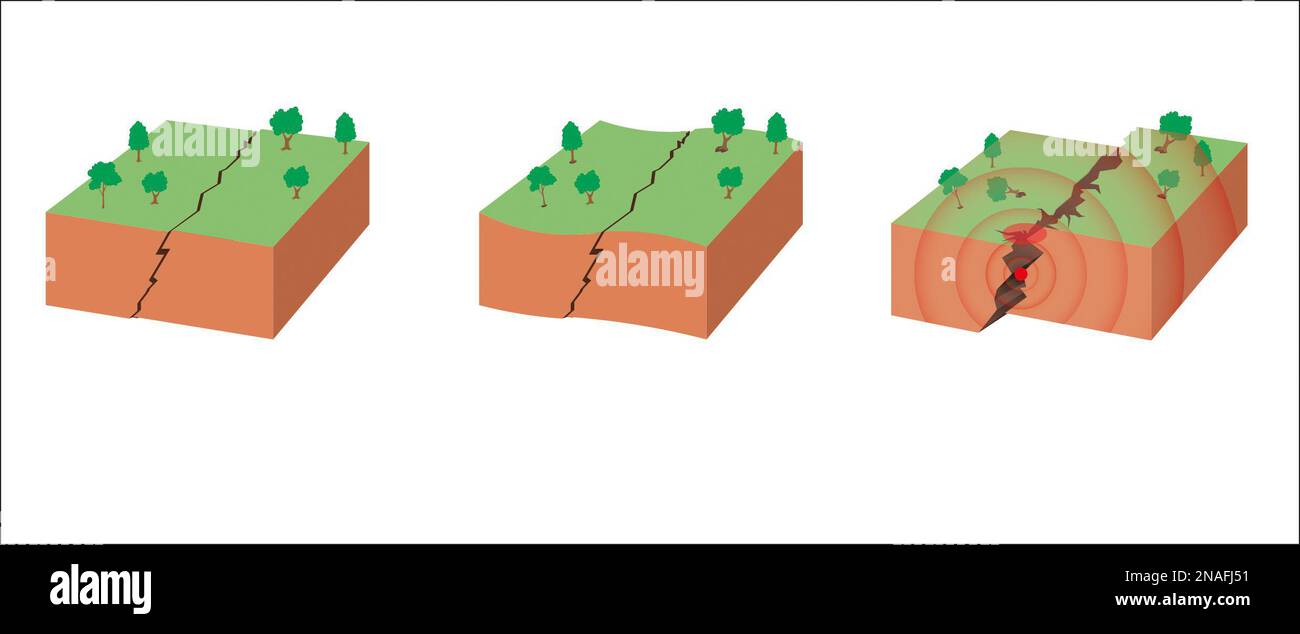

Deep underground, tectonic plates are stuck. They want to move—the Pacific Plate is constantly trying to grind past the North American Plate—but they are jagged and rough. They snag. Stress builds up over decades, compressing the rock like a giant metal spring being wound too tight.

Eventually, the rock reaches its yield point. It snaps.

This point of failure is the hypocenter. The spot directly above it on the surface is the epicenter. When that snap happens, the energy released is mind-boggling. To give you an idea, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake releases roughly the same energy as 33 megatons of TNT. That’s not just a "shake." That’s a massive redistribution of the Earth's crust. During the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan, the main island of Honshu actually moved 8 feet to the east. The entire planet's axis shifted by about 6.5 inches.

👉 See also: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

The Magnitude Myth

We need to talk about the Richter scale, or more accurately, the Moment Magnitude Scale ($M_w$) that scientists use now. It’s logarithmic. That means a magnitude 7 isn’t just "a bit worse" than a magnitude 6. It’s 10 times the amplitude and about 32 times more energy.

People often ask, "How long does the shaking last?" For a small quake, maybe 2 to 5 seconds. For a massive magnitude 9.0 like the one that hit Sumatra in 2004, the ground can shake for five solid minutes. Imagine trying to stand up on a moving boat for five minutes while the boat is also trying to throw you through a window. You can’t. You basically just have to crawl and hold on.

The Aftermath: The "Second" Earthquake

What happens in an earthquake doesn't end when the shaking stops. In many ways, the thirty minutes following the main shock are the most dangerous.

Fire is the silent killer. In the 1906 San Francisco disaster, it’s estimated that 90% of the city’s destruction was caused by fires, not the shaking. Gas lines break. Water mains—which the firefighters need—also break. You’re left with a city on fire and no way to put it out.

✨ Don't miss: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

Then there are aftershocks. These aren't just "little echoes." They are full-blown earthquakes that happen because the crust is trying to settle into its new position. If a building was structurally weakened by the main shock, a medium-sized aftershock can be the final nudge that brings it down. Dr. Lucy Jones, one of the world's leading seismologists, often points out that aftershocks follow a predictable decay pattern, but they can continue for years.

Tsunami Triggers

If the fault line is under the ocean and it moves vertically, it displaces the entire column of water above it. This creates a tsunami. In the deep ocean, you wouldn't even notice a tsunami passing under your boat; it might only be a foot high. But as it hits shallow water, it slows down and piles up into a wall of water. It’s not a single wave, either. It’s more like a tide that keeps coming in and never stops, carrying houses, cars, and debris with it.

Surviving the Shake: Actionable Reality

We used to be told to stand in a doorway. Don’t do that. In modern houses, doorways are no stronger than any other part of the frame, and the door swinging back and forth can crush your fingers or knock you out.

The gold standard is Drop, Cover, and Hold On.

- Drop to your hands and knees. This prevents you from being thrown to the ground and keeps you low.

- Cover your head and neck with your arms. If there’s a sturdy table nearby, crawl under it.

- Hold On to your shelter. Earthquakes move things. If you’re under a table, the table is going to try to slide away from you. You need to move with it.

Practical Next Steps for Right Now:

- Identify your "Tall Stuff": Look around your room. Is that heavy IKEA bookshelf anchored to the wall? If not, that’s your biggest threat. Buy a $10 furniture strap kit. It takes five minutes to install and literally saves lives.

- The Shoe Rule: Keep a pair of sturdy, old sneakers and a flashlight in a bag tied to the leg of your bed. If an earthquake happens at 2 AM, the floor will be covered in broken glass from picture frames and windows. You cannot evacuate or help your family if your feet are shredded.

- Water Storage: You need one gallon per person per day. Aim for three days minimum. When the pipes break, they often suck in contaminants, making the remaining water in the lines undrinkable.

- Know Your Shut-offs: Learn where your gas main is and keep a wrench nearby. Only shut it off if you smell gas, as turning it back on requires a professional technician and can take days or weeks during a disaster.

Earthquakes are inevitable in many parts of the world. We can't stop the plates from moving, but understanding the physics of the shake makes the experience a lot less like a supernatural event and more like a manageable physical reality. Prepare for the "non-structural" stuff first—the falling TVs and the broken glass—because that's what happens in an earthquake most of the time.