Honestly, math isn't always about finding a single "x" value. Sometimes, it’s about breaking things down before they break you. That's exactly where x cubed plus 8 comes in. Most people see it and think it's just another boring homework problem, but it’s actually a classic example of a "Sum of Cubes." If you don't know the specific pattern for it, you're basically stuck staring at a wall.

It looks simple. It’s short. But it has teeth.

The Anatomy of the Sum of Cubes

You can't just take the cube root and call it a day. If you try to say $x^3 + 8 = (x+2)^3$, you're going to fail your exam. Period. Expanding $(x+2)^3$ gives you a mess of middle terms like $6x^2$ and $12x$ that simply don't exist in our original expression. This is a common pitfall. Students do it all the time because the brain wants math to be symmetrical and easy. It rarely is.

To handle x cubed plus 8, you need a specific blueprint. Mathematicians call it the Sum of Cubes formula. It looks like this: $a^3 + b^3 = (a + b)(a^2 - ab + b^2)$.

In our specific case, $a$ is just $x$. The number 8 is actually $2^3$, so $b$ is 2. When you plug those into the template, the magic happens. You get $(x + 2)(x^2 - 2x + 4)$. It’s clean. It’s elegant. But more importantly, it's correct.

Why x cubed plus 8 is the Ultimate "Gotcha" Problem

Why do teachers love this one? It's because of the signs. Look at the result again: $(x + 2)(x^2 - 2x + 4)$. Notice that minus sign in the middle of the second parenthesis? That's the "SOAP" rule in action. SOAP stands for Same, Opposite, Always Positive.

- Same: The first sign is the same as the original problem (+).

- Opposite: The second sign is the opposite of the original (-).

- AP: The last sign is Always Positive (+).

If you forget that middle minus sign, your entire calculation for the roots or the graph will be trash. You'll end up with a parabola that doesn't touch the axis where it should.

Graphing the Beast

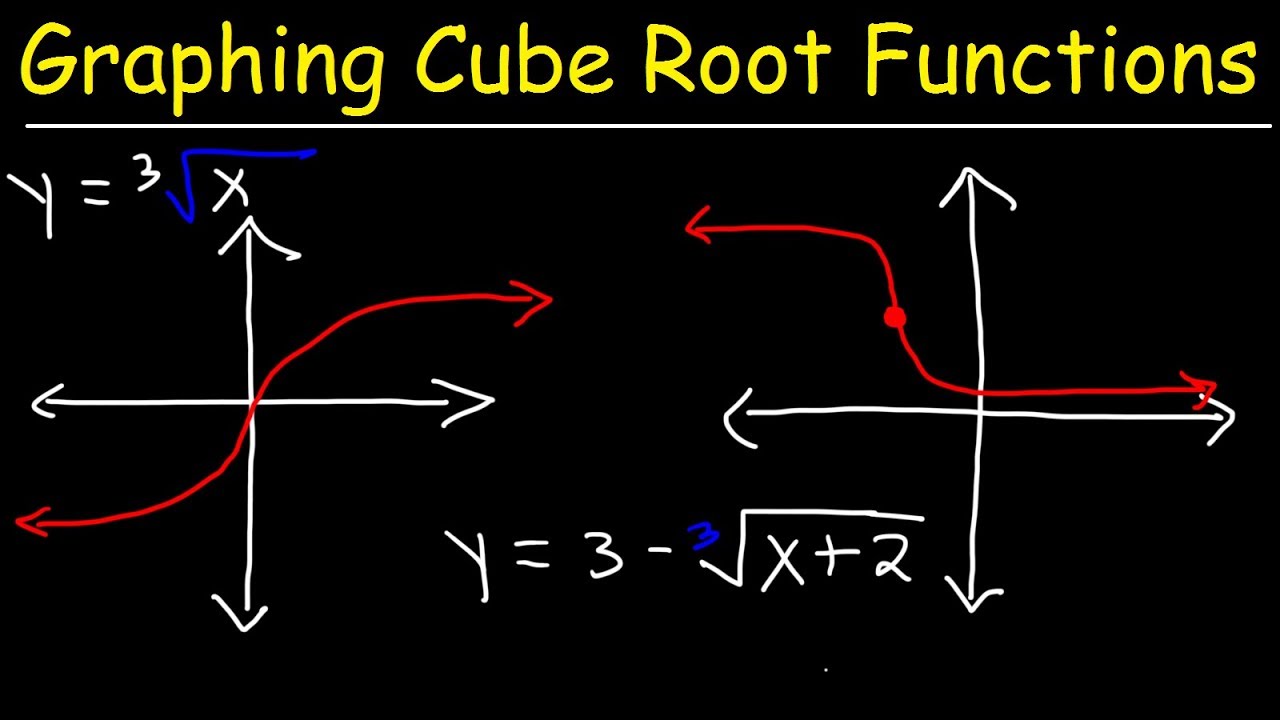

When you graph $y = x^3 + 8$, it doesn't look like a standard "U" shape. It’s a cubic function. It starts deep in the negatives, crawls up, does a little wiggle at the y-intercept (which is 8, obviously), and then shoots off into the atmosphere.

Wait. Think about the x-intercept.

If you set $x^3 + 8 = 0$, you get $x^3 = -8$. Since you can take the cube root of a negative number (unlike square roots, which get all "imaginary" on us), $x = -2$. That is the only real root. The other two roots? They’re hidden inside that quadratic part we factored earlier: $x^2 - 2x + 4$.

If you try to solve $x^2 - 2x + 4 = 0$ using the quadratic formula, you’ll find that the discriminant is negative. Specifically, $2^2 - 4(1)(4) = -12$. This means you’re looking at complex numbers involving $i$. This is why the graph only crosses the x-axis once.

It’s a bit of a lonely graph.

Real-World Applications (Yes, They Exist)

You might think you'll never use x cubed plus 8 outside of a classroom. You're mostly right, unless you're into computer science or structural engineering.

In 3D modeling, cubic equations help define smooth curves called splines. When you’re designing the curve of a car door or the aerodynamic wing of a drone, you’re essentially manipulating polynomials. While the engineers usually have software to do the heavy lifting, understanding the factoring of terms like $x^3 + 8$ is fundamental to understanding how the software handles intersections of volumes.

Coding the Logic

If you're a programmer working in Python or C++, you might write an algorithm to find roots of polynomials. Testing your code against a known sum of cubes is a standard "sanity check." Because we know exactly what the real and imaginary roots are for x cubed plus 8, we can use it to verify if a numerical solver is accurate.

If the code says the root is -2.0000001, we know we have a precision error. If it says the root is 2, we know we have a logic error.

Common Misconceptions That Kill Grades

People constantly try to factor this as $(x+2)(x-2)$. That’s for $x^2 - 4$. Don't mix up your squares and your cubes. It’s a fatal error in algebra.

Another weird one? Thinking that $x^3 + 8$ can't be factored at all. Some people assume that because it's a "sum" (and the sum of squares $x^2 + 4$ is prime over real numbers), that the sum of cubes is also prime. Not true. Cubes are much more forgiving than squares. They always have at least one real linear factor.

The Quadratic Part is Always Prime

Here is a pro tip: in the result $(x + 2)(x^2 - 2x + 4)$, that second part—the trinomial—will never factor further using basic integers. Don't waste twenty minutes of your life trying to find two numbers that multiply to 4 and add to -2. They don't exist in the world of whole numbers. You’re done. Walk away.

✨ Don't miss: The Solar System Family Portrait Voyager Captured: Why It Still Gives Us Chills

Practical Steps for Mastering Polynomials

If you're staring at a test paper and see a cubic expression, follow this workflow:

- Check for a GCF: Always look for a Greatest Common Factor first. In x cubed plus 8, there isn't one. But if it were $2x^3 + 16$, you’d pull out a 2 first.

- Identify the Cubes: Is the first term a cube? Yes ($x$). Is the second term a cube? Yes ($2^3 = 8$).

- Apply SOAP: Use the Same, Opposite, Always Positive rule for the signs.

- Plug and Play: Put your "a" and "b" values into the $(a+b)(a^2-ab+b^2)$ template.

- Verify the Intercept: Plug in $x = 0$ to find the y-intercept. For this equation, it’s 8.

- Stop Factoring: Remember that the quadratic piece is unfactorable. Don't overthink it.

Mastering this specific pattern makes you faster. Speed in math isn't just about being "smart"; it's about recognizing patterns so you don't have to reinvent the wheel every time you see an exponent. You’ve got this.