On Valentine’s Day in 1990, a robotic explorer turned its gaze toward home for one final look. It was about 3.7 billion miles away. Imagine that distance for a second. It's almost impossible to wrap your head around. Voyager 1 had finished its primary mission of touring the gas giants, and it was screaming toward the edge of interstellar space at 40,000 miles per hour. But before the cameras were powered down forever to save energy, Carl Sagan had a crazy idea. He wanted the craft to turn around. He wanted a "family portrait."

NASA engineers weren't exactly thrilled about the plan. There were legitimate technical concerns. Pointing the cameras so close to the Sun could fry the delicate Vidicon sensors. It was a risky, sentimental gesture in a field driven by cold, hard data. But Sagan won the argument. The result was the solar system family portrait Voyager beamed back to Earth—a series of 60 frames that captured six planets and our Sun in a single mosaic. It remains, quite frankly, the most humbling image ever taken by human hands.

The Day the Cameras Turned Back

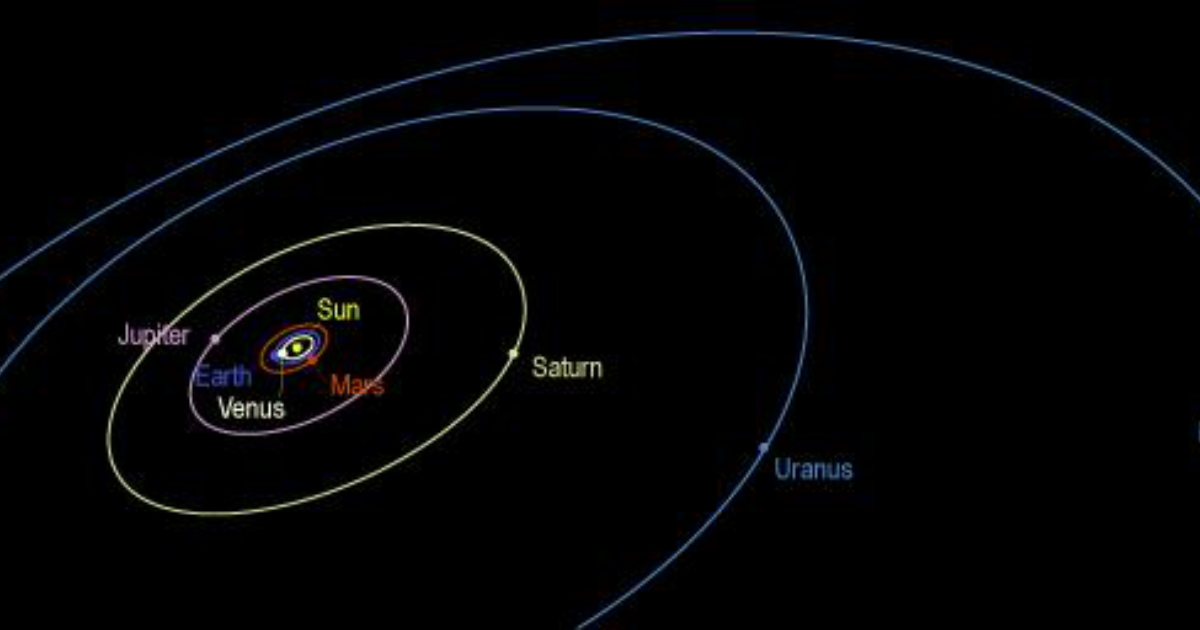

The command sequence was sent up in early 1990. Voyager 1 was high above the ecliptic plane—the flat "pancake" where most planets orbit. This gave it a literal bird’s-eye view of our neighborhood. Most people know the "Pale Blue Dot," but that was just one tiny speck in a much larger composition. The full mosaic includes Neptune, Uranus, Saturn, Jupiter, Earth, and Venus.

Mars was lost in the glare of the Sun. Mercury was too close to be seen. Poor Pluto (still a planet back then!) was too small and dim to show up on the sensors.

The logistics were a nightmare. Because the Sun is so bright, the team had to use different exposure times for different planets. Jupiter and Saturn are big and reflect a lot of light; Uranus and Neptune are dark and distant. It took months for the data to trickle back to Earth through the Deep Space Network. When the team finally processed the images, they didn't see high-definition globes. They saw dots. Smudges. Faint glints of light against a sea of nothingness.

👉 See also: How to change home and work in Google Maps without losing your mind

Why the Pale Blue Dot stole the show

Even though the solar system family portrait Voyager gave us a look at the "Big Five" gas giants, the Earth frame changed everything. We're talking about a pixel. Not even a full pixel. Just 0.12 pixels in size. It’s a tiny blueish-white speck suspended in a sunbeam, which was actually an optical artifact caused by sunlight scattering inside the camera lens.

It looks like a mistake. It looks like dust on a lens. But that "dust" is us.

Sagan’s subsequent reflection on this image is famous, but people often forget the technical reality of that moment. By taking that photo, we essentially retired Voyager 1’s eyes. Shortly after the mosaic was completed, the cameras were switched off. The software was removed to free up memory for the interstellar instruments that measure magnetic fields and plasma. Voyager 1 is now blind, wandering the dark between stars, but it left us with a mirror.

The Tech Behind the Magic

You have to remember that Voyager's technology is ancient. We're talking about computers with less power than the key fob you use to unlock your car. The cameras used Vidicon tubes—essentially old-school television tech—rather than the CMOS or CCD sensors in your smartphone.

- Data Storage: The images weren't sent instantly. They were recorded onto a digital tape recorder (DTR). Yes, a literal spinning tape.

- Transmission Speed: Data moved at a sluggish 1.4 kilobits per second. To get the full family portrait back to Earth, it took a massive amount of patience.

- Pointing Accuracy: The craft had to be oriented with extreme precision using tiny thruster bursts. If it wobbled, the planets would be streaks instead of dots.

It’s easy to look at the grainy, noisy images today and think they look "bad" compared to the high-res shots from the James Webb Space Telescope. But that’s missing the point. The solar system family portrait Voyager wasn't about detail; it was about perspective. It showed the scale of the void. Seeing Jupiter and Earth in the same "set" of photos makes you realize how lonely the solar system actually is.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Portrait

A common misconception is that you can see all the planets lined up in a row. That’s not how space works. The planets were scattered all over their orbits. NASA had to point the camera at specific coordinates in the blackness, snap a shot, and then move to the next. The "mosaic" is a construction of these various points of view.

Another myth? That Voyager was "leaving" the solar system when it took the photo. Technically, it was leaving the neighborhood of the planets. Even now, decades later, Voyager hasn't truly left the solar system. It has passed the heliopause—where the solar wind meets the interstellar medium—but it hasn't reached the Oort Cloud. It won't clear the outer edge of the Oort Cloud for another 30,000 years. Space is big. Really big.

The "Missing" Planets

Why does the portrait feel incomplete to some?

Mercury is simply too small and too close to the Sun’s massive glare. Even with the best filters, Voyager’s 1970s optics would have been blinded. Mars was also a casualty of geometry; the scattered sunlight in the camera system washed out the Red Planet's faint glow. It’s a reminder that even our most advanced (for the time) tech had limits. We are at the mercy of physics.

The Legacy of a Grainy Photo

The solar system family portrait Voyager created is a cultural touchstone. It’s been used in documentaries, art installations, and political speeches. Why? Because it’s the ultimate "ego check." Every war ever fought, every "great" leader, and every tragedy occurred on that 0.12-pixel dot.

💡 You might also like: How to Transfer Music to iMovie Without Losing Your Mind

Candy Hansen-Koharcheck, a scientist on the Voyager imaging team, often talks about how stressful those final frames were. There was no guarantee they would work. If the Sun had damaged the cameras early, they might have lost the chance to gather other precious data. But the gamble paid off. It gave humanity a sense of "home" that didn't stop at a border or a coastline.

Voyager Today: The Silent Traveler

Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are still talking to us, though it’s more of a whisper now. They are powered by Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) that use the heat from decaying plutonium-238. Every year, the power drops by about 4 watts. We’re currently in the "triage" phase of the mission. NASA engineers are turning off heaters and non-essential systems one by one to keep the radio alive.

They won’t last forever. By roughly 2030, we will likely lose contact. Voyager 1 will become a silent ghost ship, carrying a Golden Record with our sounds and music, drifting toward a star called AC +79 3888 in the constellation Camelopardalis. It’ll get there in about 40,000 years.

How to Explore the Portrait Yourself

You don’t need a PhD to appreciate the data. NASA has made the raw files and the reconstructed mosaics available to the public.

- Check the JPL Photojournal: Search for image PIA00451. This is the official wide-angle view of the mosaic.

- Use NASA’s "Eyes on the Solar System": This is a free web-based app. You can actually "ride along" with Voyager and see exactly where it was pointing when it took the portrait.

- Read the Original Paper: For the real nerds, look up the 1990 reports in Science magazine. They detail the precise angles and light levels used to capture the planets.

The solar system family portrait Voyager snapped is a reminder that we are a spacefaring species. We aren't just stuck on the ground; we have extensions of our senses out in the deep dark. It encourages a kind of planetary stewardship that is more relevant now than ever. When you see how small the Earth is against the backdrop of the outer planets, our local problems start to look a little different.

To truly understand our place in the cosmos, stop looking at the high-definition, color-corrected images of Mars for a moment. Instead, look at that grainy, noisy, 1990 mosaic. Look for the speck of dust in the sunbeam. That’s the only home we’ve ever known, captured by a machine that is now further away from us than anything else in history. It's a haunting, beautiful, and fundamentally human achievement.

Next Steps for the Curious

- Download the High-Res Mosaic: Visit the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) website to download the 60-frame mosaic in its full, restored glory.

- Track Voyager 1 in Real-Time: Use the "Mission Status" page on NASA’s Voyager website to see exactly how many billions of miles away the spacecraft is right now, down to the second.

- Watch the "Last Pictures" Documentary: Explore the philosophical side of why we send images into space and what happens to them when we are gone.