He lived to be 99. Think about that for a second. When William Henry Jackson photographer and Civil War veteran was born in 1843, photography was a messy, dangerous chemistry experiment. By the time he died in 1942, he had seen the birth of color film, the rise of Hollywood, and the invention of the jet engine. But it wasn't just his longevity that mattered. It was his glass plates.

Without Jackson, Yellowstone might just be a collection of private resorts and strip mines today.

Most people think of the National Parks as an inevitability. We assume the government just saw a pretty waterfall and decided to protect it. That’s not what happened. In the 1870s, the American West was viewed as a giant ATM. You went in, you took the timber, you mined the gold, and you moved on. When rumors of "hell bubbling over" in Wyoming reached Washington D.C., politicians laughed. They thought the stories of 200-foot water sprouts and boiling mud were tall tales from drunk mountain men.

Then came the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871.

Why the Hayden Survey Changed Everything

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden was a man with a mission, but he knew words wouldn't be enough to convince a skeptical Congress. He needed proof. He hired Jackson, who was then running a small portrait studio in Omaha, to be the official photographer.

It was a brutal gig.

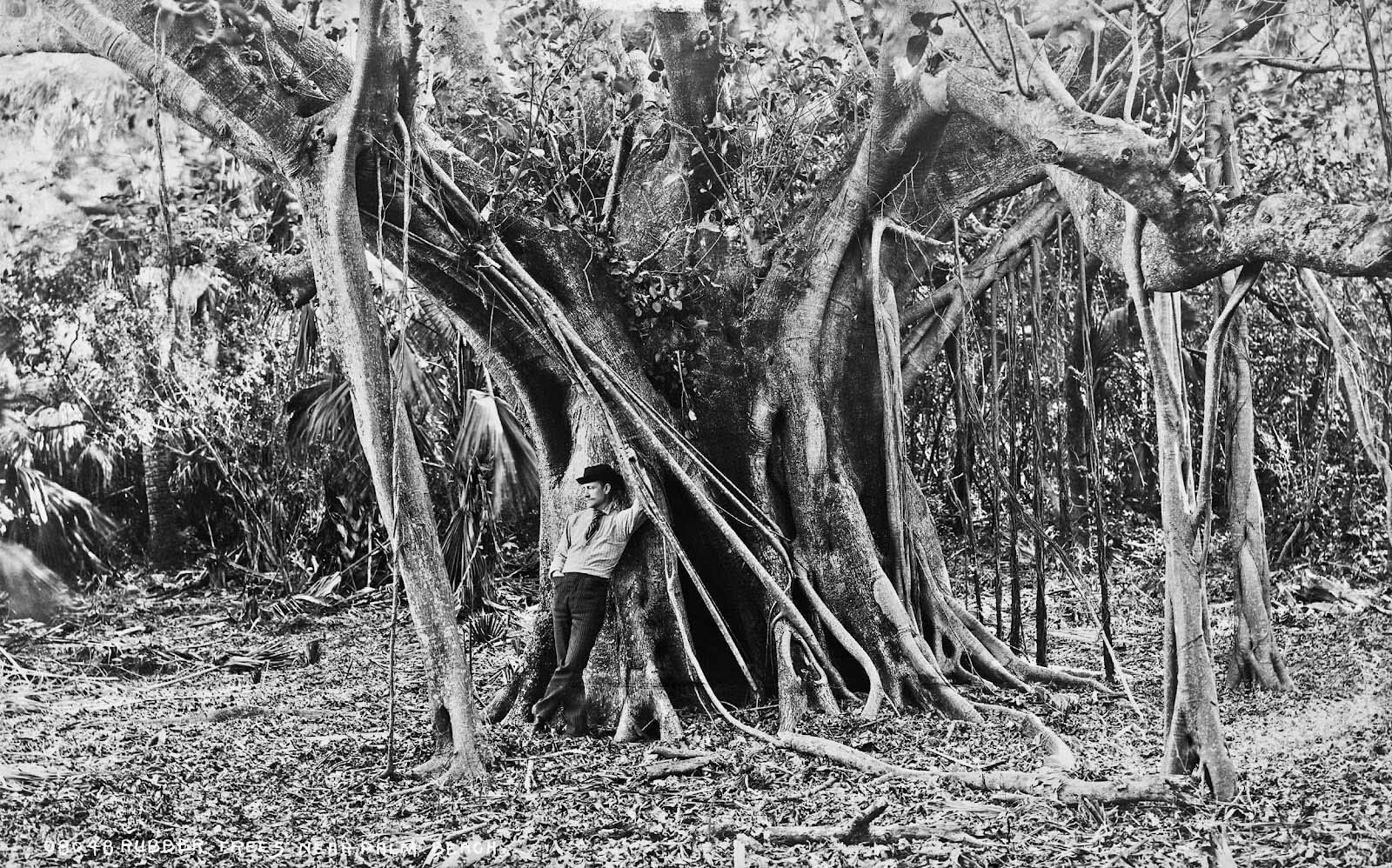

Today, we complain if our smartphone takes two seconds to focus. Jackson was hauling hundreds of pounds of equipment on the backs of stubborn mules. We’re talking about massive glass plates, "wet-collodion" chemicals that had to be mixed on the spot, and a portable darkroom tent that caught the wind like a sail. If the chemicals got too hot, they failed. If a dust mote landed on the plate, the shot was ruined. If the mule fell off a cliff, your entire year's work was shattered glass.

The Chemistry of the Wild

Imagine standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. The wind is howling. You have to sensitize a glass plate in a dark tent, rush it to the camera, take a multi-second exposure while hoping the tripod doesn't vibrate, and then rush back to the tent to develop it before the plate dries.

👉 See also: Desi Bazar Desi Kitchen: Why Your Local Grocer is Actually the Best Place to Eat

Jackson did this over and over.

His photos weren't just "nice." They were undeniable. When those prints were circulated among members of Congress in early 1872, the debate changed instantly. You couldn't call it a "frontier myth" when you were looking at the intricate details of Old Faithful or the dizzying scale of the Lower Falls. On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act.

Jackson's lens had literally turned scenery into a national treasure.

The Misunderstood Artist

People often lump Jackson in with Ansel Adams, but they were doing completely different things. Adams was an artist using nature as a medium for high-contrast drama. Jackson? He was a pioneer and a documentarian.

He wasn't trying to be "moody." He was trying to be accurate.

His work with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) took him into places that white settlers had barely touched. He captured the first known photographs of the prehistoric cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde. He photographed the "Mountain of the Holy Cross," a peak in Colorado with a natural cross-shaped snowfield that many people believed was a religious hoax until Jackson proved it existed.

There’s a gritty, honest quality to his work. He didn't airbrush the reality of the West. You see the mud. You see the exhaustion in the eyes of the surveyors. You see the sheer, terrifying scale of the Rocky Mountains compared to a tiny human figure standing on a ledge.

✨ Don't miss: Deg f to deg c: Why We’re Still Doing Mental Math in 2026

Beyond the Big Camera

Eventually, the technology caught up with his ambition. Jackson didn't stay stuck in the era of glass plates. He became a partner in the Detroit Publishing Company, where he pioneered the use of "Photochrom" processes. This was basically a way to turn black-and-white negatives into colorized prints using lithographic stones.

It changed how Americans saw their own country.

Suddenly, the West wasn't just gray and white. It was the red of the Utah desert and the deep turquoise of the Pacific. He helped create a visual vocabulary for the American dream.

The Later Years and the Myth

What’s wild is that Jackson became a celebrity in his own right as he aged. He was the "Old Man of the Mountains." In his 80s and 90s, he was still traveling, still painting (he was a trained illustrator before he was a photographer), and still telling stories. He wrote his autobiography, Time Exposure, which is honestly a must-read if you want to understand the transition from the frontier to the modern world.

He didn't just look backward, though. He was fascinated by the way photography became accessible to everyone. He saw the Kodak Brownie change the world and he loved it. He wasn't a gatekeeper. He just wanted people to see.

What Most People Get Wrong About Jackson

There’s this idea that he was just a lucky guy with a camera. That he happened to be in the right place at the right time.

That’s nonsense.

🔗 Read more: Defining Chic: Why It Is Not Just About the Clothes You Wear

The technical skill required to produce his 18x22 inch "mammoth plates" in the middle of a wilderness is staggering. One mistake and you lose the shot. He had to understand light, chemistry, geology, and animal husbandry all at once. He was an athlete, an explorer, and a scientist.

Also, he wasn't just a "nature photographer."

If you look at his later work for various railroads, you see a man documenting the industrialization of America. He photographed the iron horses—the steam engines—cutting through the mountains he had previously explored on foot. He documented the destruction as much as the preservation. There’s a complexity there that often gets ignored in the "Saint of the National Parks" narrative.

How to Experience Jackson’s Work Today

If you want to actually see what he saw, don't just look at a low-res JPEG on Wikipedia.

The Library of Congress holds a massive digital collection of his work. When you zoom in on a high-resolution scan of one of his glass plates, the detail is haunting. You can see the individual leaves on a tree a mile away. You can see the texture of the wool in a surveyor’s jacket.

- Visit the Scotts Bluff National Monument in Nebraska. They house one of the largest collections of his original sketches and paintings.

- Check the Smithsonian Institution. They hold many of his most important geological photographs.

- The Jackson Hole Historical Society often features his work, given his deep connection to the Teton region.

Actionable Takeaways for History Buffs and Photographers

If you're inspired by Jackson's legacy, there are a few ways to apply his "pioneer spirit" to how you view the world today:

- Study the "Wet Plate" process. There is a massive revival in tintype and glass plate photography. Learning how to handle the chemistry helps you appreciate the sheer difficulty of 19th-century field work.

- Document your local "Yellowstone." You don't need a mountain range. Jackson's genius was showing people what they couldn't see for themselves. Find a local spot that deserves protection and photograph it with the intent to preserve it.

- Read "Time Exposure." It’s one of the few first-hand accounts that bridges the gap between the Civil War and World War II. It’s a masterclass in perspective.

- Look for the "Mammoth Plate" aesthetic. Large format photography (even digital) requires a slower, more deliberate pace. Try spending an entire day taking just five photos. Think like you only have five pieces of glass left in your pack.

Jackson wasn't just a guy taking pictures. He was the man who convinced a nation that some things are more valuable than the gold you can dig out of them. He taught us how to value the horizon.

To truly understand the impact of his work, look for the 1871 Hayden Survey records at the National Archives. These documents contain the original context for his most famous images, showing exactly how they were used to lobby the United States government for the creation of the world's first national park. You can also explore the Detroit Publishing Company collection at the Library of Congress to see his transition into color lithography, which helped popularize the American West for the early 20th-century travel industry.