You’ve seen them since second grade. Those neat little drawings with three circles—the Sun, the Moon, and the Earth—all lined up like pearls on a string. Usually, there’s a couple of tidy triangles representing the shadow. Simple, right? Honestly, most of those graphics are wildly misleading. If you actually tried to use a standard schoolbook diagram of a solar eclipse to predict where to stand during totality, you’d end up staring at a perfectly normal Tuesday afternoon sky, wondering where the cosmic magic went. Space is big. Like, terrifyingly big. When we squash it down to fit on a smartphone screen or a textbook page, we lose the terrifying precision required for the Moon to actually "hit" the Sun from our perspective.

The Anatomy of a Shadow: What the Lines Actually Mean

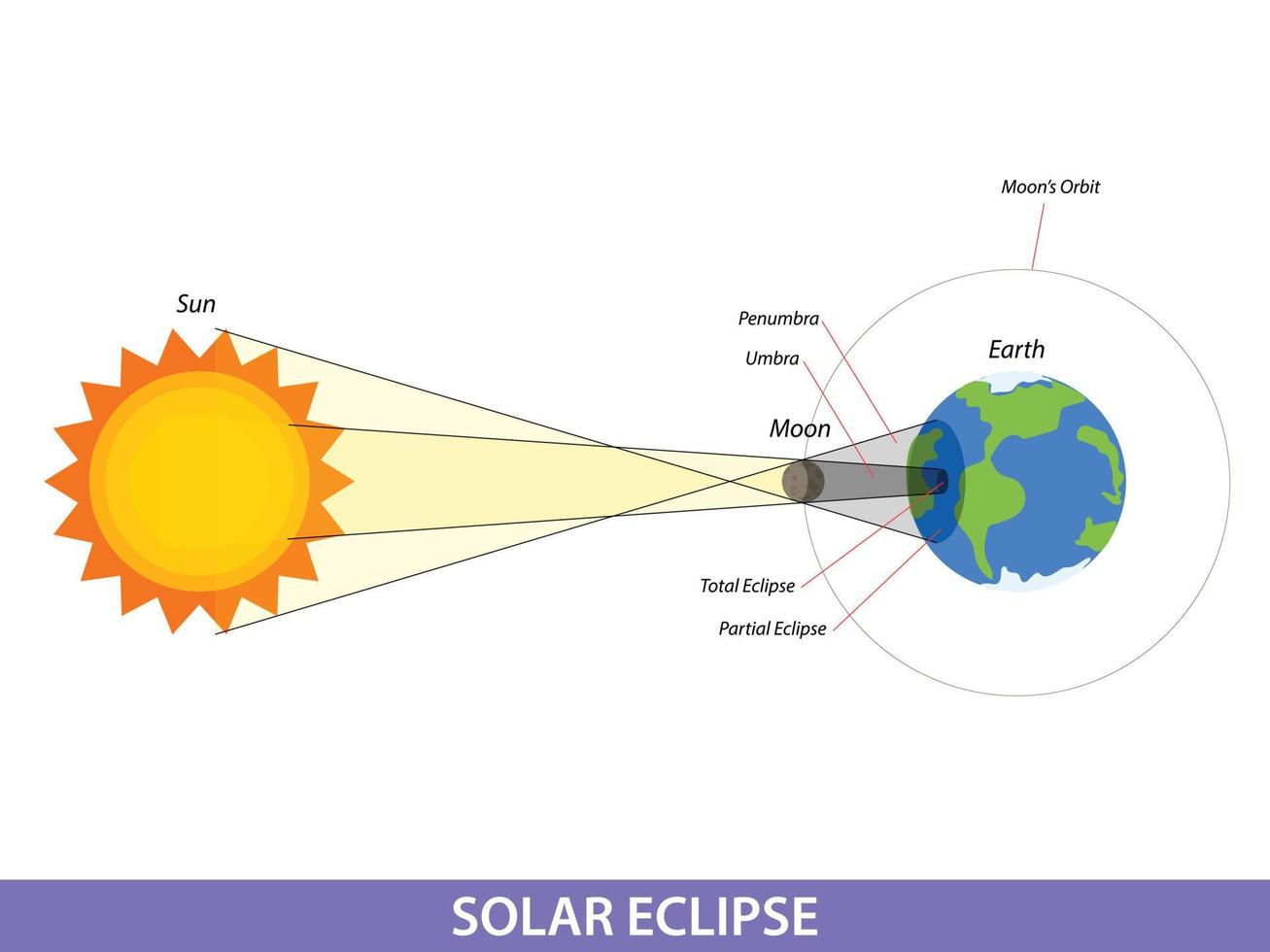

To get what’s happening, you have to look at the geometry of the shadow. It’s not just one dark blob. It’s a tapering cone. Astronomers call the darkest part the umbra. This is the sweet spot. If you are standing inside the umbra, the Moon completely blocks the Sun’s photosphere.

Then you have the penumbra. That’s the outer, lighter shadow where you only see a partial eclipse. Most people don't realize that the umbra is incredibly narrow. During the 2024 Great American Eclipse, the path of totality was only about 115 miles wide. Compare that to the size of the Earth. It’s a needle-thin scratch across the globe.

Scaling the Impossible

Let’s talk about the "lie" of the diagram. In a typical diagram of a solar eclipse, the Moon looks like it’s about a quarter of the way between Earth and the Sun. In reality? If the Earth were a basketball, the Moon would be a tennis ball 23 feet away. The Sun? That would be a massive sphere 1.7 miles down the road.

Trying to draw that to scale is impossible. You’d just have a bunch of invisible dots. So, we cheat. We bring the Sun closer and make the Moon bigger. This helps us see the logic of the alignment—the Syzygy—but it ruins our intuition for how rare these events actually are. The Moon’s orbit is tilted at about 5 degrees relative to Earth’s orbit around the Sun. Most months, the "New Moon" shadow misses Earth entirely, passing harmlessly above or below us into the vacuum.

👉 See also: Grad Fahrenheit vs Grad Celsius: Why We Still Use Two Different Worlds

Understanding the "Diamond Ring" and Baily’s Beads

If you look at a high-quality scientific diagram of a solar eclipse, you might see mentions of the lunar limb. The Moon isn't a smooth cue ball. It has mountains, craters, and jagged valleys. As the Moon moves into its final position, the Sun's light peeks through these valleys. This creates the "Baily's Beads" effect.

Just a second before totality, only one valley remains. That single point of brilliant light, combined with the glowing atmosphere of the Sun (the corona), creates the famous "Diamond Ring." You can’t see this on a flat, 2D diagram easily, but it’s the result of three-dimensional topography interacting with a light source 93 million miles away. It’s basically nature’s most precise shadow puppet show.

The Three Main Flavors of Eclipses

- Total Solar Eclipse: The Moon is close enough to Earth to cover the Sun completely. This only happens because of a bizarre cosmic coincidence: the Sun is 400 times larger than the Moon, but it’s also about 400 times further away. They look the same size in our sky.

- Annular Solar Eclipse: The Moon is at "apogee" (its farthest point from Earth). It looks smaller. It can't cover the whole Sun, so you get a "ring of fire." Your diagram of a solar eclipse for this version would show the umbra ending before it reaches Earth’s surface.

- Partial Solar Eclipse: You’re just in the penumbra. The Sun looks like a bitten cookie.

Why 2D Diagrams Fail to Show "Eclipse Seasons"

Every year, people ask: "If the Moon goes around the Earth every month, why don't we have a solar eclipse every month?"

A standard side-view diagram of a solar eclipse makes it look like it should happen constantly. But we live in a 3D world. Think of the Earth's orbit as a flat sheet of paper. The Moon’s orbit is another sheet of paper tilted at an angle. They only cross at two points, called nodes. An eclipse can only happen when a New Moon occurs right at one of those nodes. This happens roughly every six months, creating "eclipse seasons."

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center uses incredibly complex data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to map these shadows. They don't just draw a circle; they map the actual rugged silhouette of the Moon onto the specific terrain of Earth. If the shadow hits the Andes mountains, the shape of the eclipse changes. It’s not a perfect oval; it’s a warped, jagged polygon moving at over 1,500 miles per hour.

Predicting the Future with the Saros Cycle

If you want to feel small, look up the Saros Cycle. Ancient Babylonians figured this out without computers or telescopes. They noticed that nearly identical eclipses repeat every 18 years, 11 days, and 8 hours.

Because of that extra 8 hours, the Earth has rotated a third of the way around. This means the "same" eclipse happens again, but one-third of the way across the globe. It takes three Saros cycles (about 54 years) for an eclipse to return to roughly the same longitude. When you see a diagram of a solar eclipse path from the year 1900 next to one from 2024, you can see the family resemblance.

🔗 Read more: What Are the Different Kinds of Computer: The 2026 Reality Check

Practical Steps for Your Next Observation

Don't just stare at the map. If you're planning to catch the next big one—like the 2026 eclipse over Spain and Iceland—you need to prepare.

- Check the Altitude: A 2D map doesn't show you the weather. A diagram might say you're in totality, but if you're behind a mountain range in the afternoon, the Sun might be blocked by rock before the Moon even gets there.

- Verify the "Centerline": The closer you are to the middle of the path on the diagram of a solar eclipse, the longer totality lasts. Being at the edge might give you 30 seconds of darkness; being in the center could give you four minutes.

- Get ISO-certified glasses: Seriously. Even a 99% eclipsed Sun can cook your retinas. The diagram shows the Sun as a yellow circle, but it's a nuclear furnace. Use "ISO 12312-2" rated viewers.

- Look Down: During the partial phases, look at the shadows cast by tree leaves. The small gaps between leaves act as pinhole projectors, scattering hundreds of tiny crescent-shaped "diagrams" of the eclipse across the sidewalk.

Instead of just looking at a static image, download an interactive eclipse tracker like Time and Date or Solar Eclipse Guide. These apps use real-time orbital mechanics to show you exactly what the "diagram" looks like from your specific GPS coordinates. Transitioning from a flat drawing to a 3D understanding is the difference between reading a menu and eating the meal.