You've been there. It’s 4:45 PM on a Friday. You just merged a feature that passed all the CI checks, but suddenly, production is screaming. Errors are spiking in Sentry. You do the responsible thing: you hit the panic button and run a git revert. The site stabilizes. You breathe.

But Monday morning comes around. You fix the bug that caused the crash. Now you want that feature back. You try to merge your branch again, but Git—in its infinite, cold logic—tells you there's nothing to merge. Or worse, the code just... isn't there. This is the messy reality of the revert of revert git workflow. It's a double-negative that trips up even senior engineers because it defies how we naturally think about "undoing" an undo.

The Logical Trap of the Revert Command

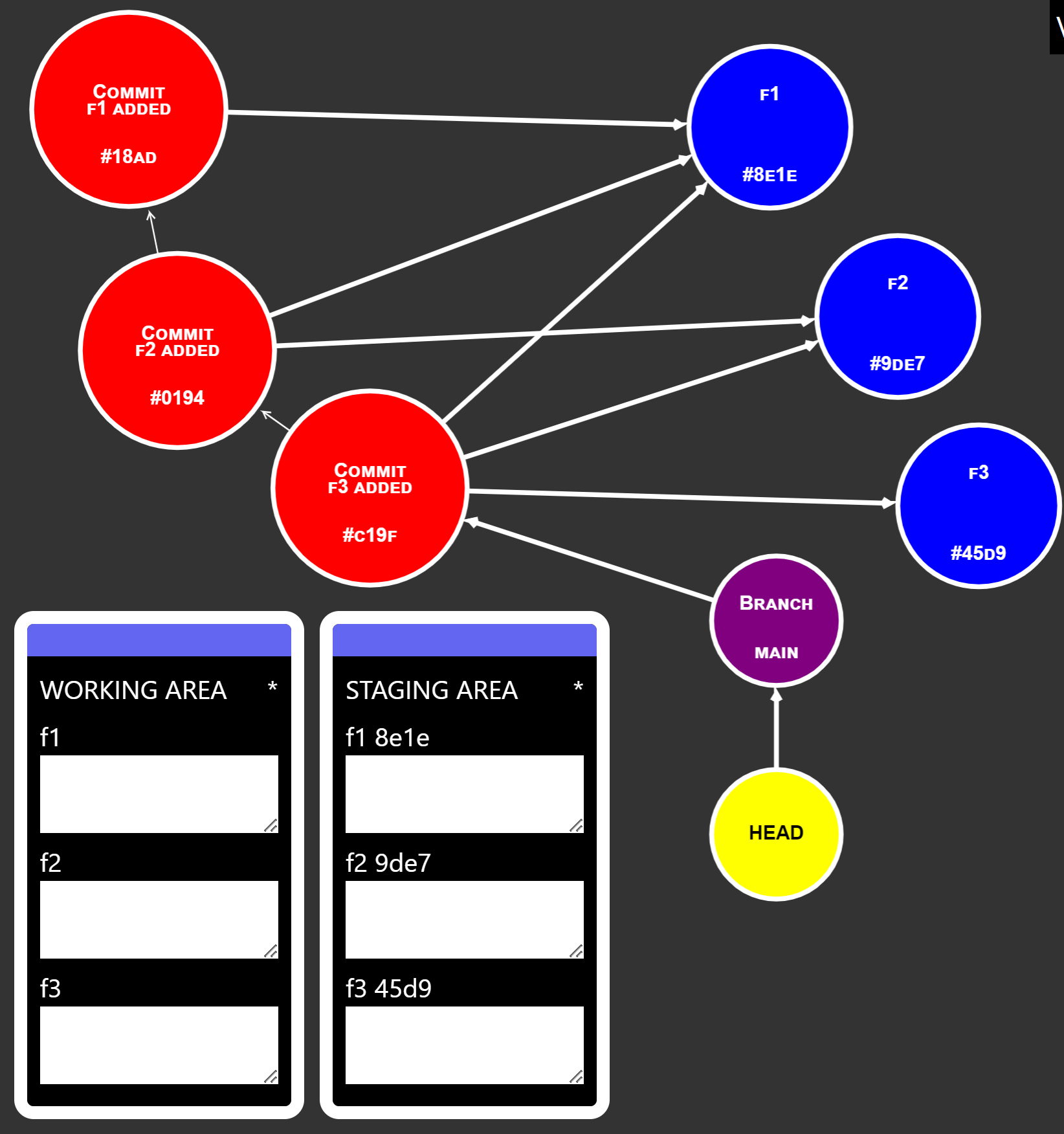

When you run git revert, you aren't actually deleting history. Git is a giant ledger. It doesn't use an eraser; it just writes a new entry that says, "Do the exact opposite of what happened in commit X."

If commit X added a line, the revert commit removes it.

✨ Don't miss: Boox Go Color 7 Page Turn Buttons: What Most People Get Wrong

The problem starts because Git now considers commit X "done." If you try to merge that same branch back into main, Git looks at the history and sees that the changes from commit X were already incorporated and then subsequently "undone" by the revert. It thinks you wanted those changes gone. To Git, your feature branch doesn't look like new work anymore; it looks like old news that was already rejected.

Honestly, it’s kinda like trying to re-gift a present to the same person who just returned it to the store. The store (Git) remembers the transaction. If you want that gift back in their house, you have to buy it again—or in our case, revert the revert.

How to Actually Perform a Revert of Revert Git

The most direct way to fix this is to literally revert the commit that did the reverting.

Suppose your original feature was commit A. You reverted it with commit B. To get your code back, you need to create commit C, which is a revert of B.

git log --oneline

# find the hash of the revert commit

git revert <hash-of-revert-commit>

This creates a new commit that re-applies the changes. It’s the cleanest way to handle it because it preserves the entire history of what happened. You can see the feature, the failure, the emergency fix, and the eventual restoration.

Why Not Just Rebase?

Some people suggest rebasing your feature branch or using git cherry-pick. While cherry-picking the original commits onto a new branch works, it can create a nightmare for your coworkers if they were also working on that code. You end up with duplicate commits that have different hashes but identical content. Linus Torvalds has famously discussed the "revert a merge" problem in the early days of the Linux kernel mailing lists, noting that once you revert a merge, you can't just merge that branch again. You have to revert the revert if you want those specific commits to be recognized as "active" again.

Real-World Messiness: When Things Go Sideways

Let’s look at an illustrative example. Imagine a team at a mid-sized SaaS company. They have a main branch and a develop branch. A developer merges a large UI overhaul. It breaks the checkout flow.

- The Revert: The lead dev reverts the merge commit on

main. - The Fix: The UI dev fixes the CSS bug on their original feature branch.

- The Failure: The UI dev tries to merge the feature branch back to

main. - The Ghost Code: The merge "succeeds," but the UI overhaul is missing. Only the tiny CSS fix is present.

This happens because the original merge commit is still in the history of main. Git thinks, "I already have those 50 files from the first merge, and then the user told me to remove them in the revert. I'll just keep them removed."

To fix this, the dev should have stayed on main (or a new release branch) and run revert of revert git. This signals to Git that the "removal" was the mistake, not the original feature.

The "Re-Reverting a Merge" Headache

Reverting a single commit is easy. Reverting a merge commit is a different beast entirely. When you revert a merge, you have to specify the "mainline" parent with the -m flag.

git revert -m 1 <merge-commit-hash>

When you eventually do the revert of revert git for a merge, you don't need the -m flag again. You're just reverting a regular (though destructive) commit. This is a nuance that causes a lot of "Permission Denied" or "Invalid Command" errors in the terminal.

The Nuance of Conflict Resolution

When you revert the revert, expect conflicts.

If other people have touched those same files in the meantime, Git might get confused. You aren't just applying a patch; you are toggling the state of the codebase back to a previous version while trying to respect the current reality. It requires a manual eye. Don't just git add . and pray. Open the files. Look at the markers.

Expert Strategies for Cleaner History

If you find yourself needing to revert a revert often, your branching strategy might be the culprit. Long-lived feature branches are the primary breeding ground for this mess.

- Small Atomic Commits: If you only have to revert one small thing, the "re-revert" is trivial. If you have to revert a 2,000-line merge, it's a disaster.

- Feature Flags: Instead of a git revert, flip a toggle in your dashboard. This avoids the "revert of revert git" logic entirely. The code stays in the repo; it’s just dormant. This is what companies like Netflix and GitHub do to avoid the "Friday afternoon scramble."

- The "New Branch" Method: Instead of fighting with the old branch, some experts prefer to create a completely new branch, cherry-pick the original commits, and treat it as a fresh start. It’s "dirtier" in terms of commit duplication but often easier for the human brain to grasp during a crisis.

Actionable Steps for Your Workflow

If you are staring at a broken repo right now, here is exactly what you should do.

📖 Related: How to remove all traces of jailbreak on iphone so your banking apps actually work again

First, identify the exact hash of the revert commit that you want to undo. Use git log --grep="Revert" to find it quickly.

Second, ensure your working directory is clean. You don't want uncommitted changes mingling with a complex revert.

Third, perform the revert of revert git on a fresh branch. Never do this directly on main if you can help it. Create a branch called fix/restore-feature-x, run the revert there, and then open a Pull Request. This gives your team a chance to review the "restoration" and ensures that the CI runs against the combined state of the code.

Fourth, check your logs. Run git log --graph --oneline --all to visualize the "zigzag" you just created. If the lines connect in a way that makes sense, you're golden.

Finally, if you were dealing with a merge commit, remember that the "re-revert" effectively re-introduces the entire history of that branch. If there were other bugs in that branch you haven't fixed yet, they are coming back too. There is no such thing as a partial revert of a revert. It is all or nothing. If you only want some of the code back, you are better off using git checkout <commit-hash> -- <file-path> to pluck specific files rather than messing with the revert logic.

The complexity of Git is a feature, not a bug. It forces you to be intentional about how code moves through time. The revert of revert git is simply the way we tell the story of a mistake that was corrected, then un-corrected, and finally made right.

Next Steps to Secure Your Repo:

- Verify the Hash: Locate the revert commit hash using

git log -n 5. - Test Locally: Run the

git revert <hash>on a temporary branch to see the conflict surface area. - Document the Reason: When the commit message editor pops up, don't just use the default. Explain why the original revert is being undone (e.g., "Re-applying feature X after fixing the race condition identified in #123").

- Audit the Merge: Use

git diff HEAD^after the revert to ensure every single line you expected to return has actually returned.