Venus is a nightmare. Honestly, if you look at the raw data coming back from our local neighborhood, it’s a wonder we have any clear venus planet pictures nasa has managed to curate over the decades. It’s a world of sulfuric acid rain, lead-melting temperatures, and an atmospheric pressure that would crush a nuclear submarine like a soda can.

But humans are obsessed. We keep sending cameras into the furnace.

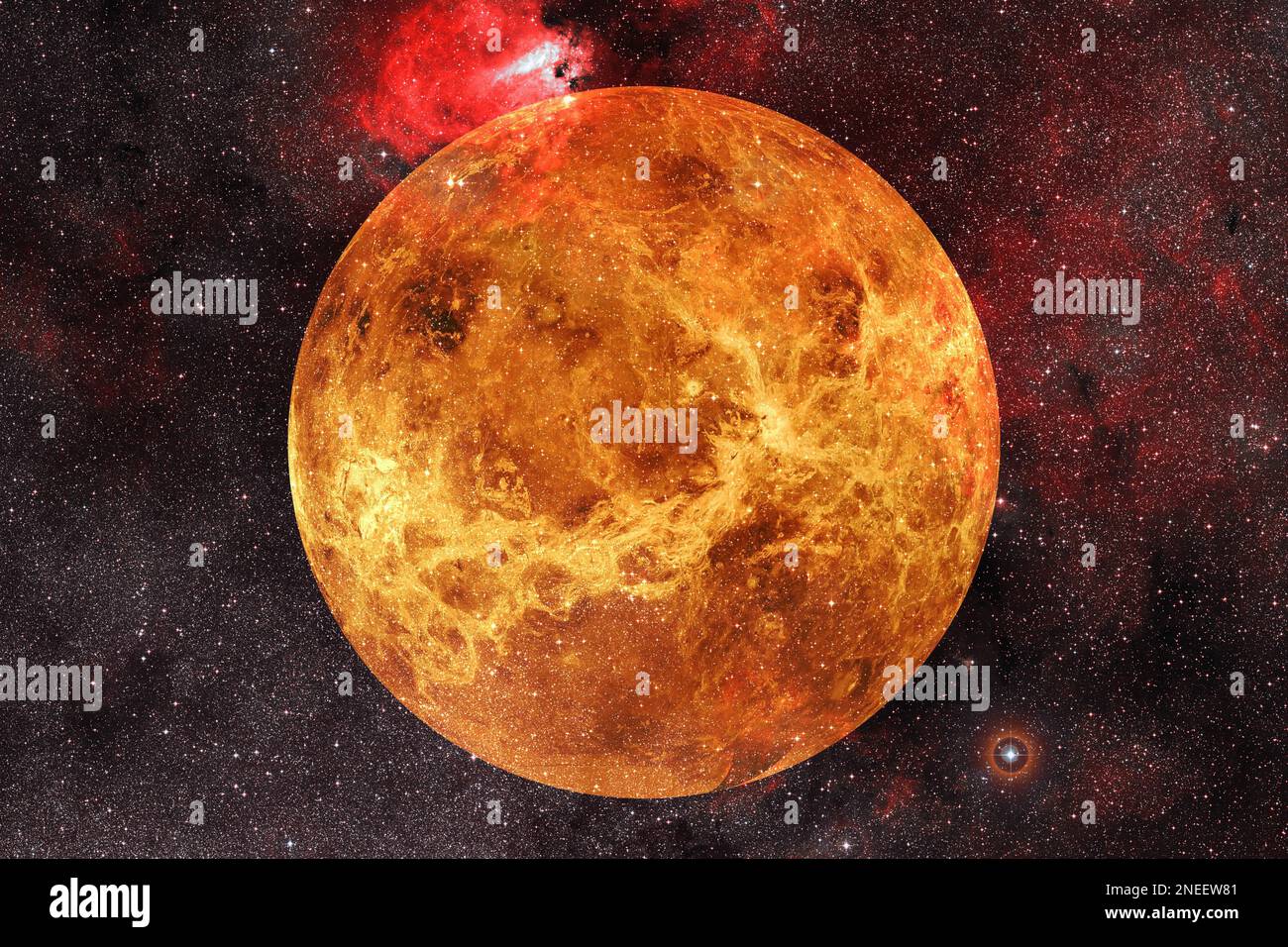

When you scroll through the official archives, you aren't just seeing snapshots. You're seeing a feat of engineering. Most of what we "see" isn't even visible light because the clouds are so thick that a standard camera would just see a featureless, yellowish-white marble. To get the "good stuff"—the cracked plains, the towering volcanoes like Maat Mons, and the strange, rippled "tesserae" terrain—NASA has to use radar. They have to peel back the sky.

The Reality Behind Those Golden Landscapes

If you've ever seen those famous orange-tinted photos of the Venusian surface, you’re likely looking at data from the Magellan mission in the early 1990s. Magellan didn't "take photos" in the way your iPhone does. It used Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) to map the topography.

NASA scientists then colorized that data. Why orange? Because the Soviet Venera probes—the only things to actually survive on the surface for a few minutes—confirmed that the thick atmosphere filters out blue light. Everything on Venus basically looks like it’s under a permanent, dirty sunset.

It’s easy to get lost in the aesthetics, but the tech is the real hero here. For example, the Akatsuki orbiter (JAXA) and NASA’s own flybys use infrared to see heat leaking out from the night side. This creates those ghostly, glowing images of the planet's dark half. It looks like a glowing coal in a fireplace. It’s eerie. It’s beautiful. And it’s incredibly difficult to capture.

Why Visible Light Photos are Actually Kind of Boring

If you stood on the surface of Venus (assuming you were invincible), your vacation photos would be disappointing. Everything would be a hazy, brownish-orange. Visibility would be poor, kinda like a heavy smog day in a valley.

This is why NASA leans so heavily on multi-spectral imaging. By looking at the planet in ultraviolet, we see the "unseen." The UV images show these massive, dark streaks in the upper clouds. Scientists still aren't 100% sure what they are. Some call them "unknown absorbers." There’s even a fringe, but serious, debate about whether these dark patches could be microbial life living in the more temperate upper atmosphere.

Think about that. We might be looking at alien biology in a grainy UV photo and not even realize it.

The Soviet Connection

We can't talk about venus planet pictures nasa without mentioning the Russians. While NASA was busy mapping the planet from above, the Soviet Union's Venera program was actually sticking the landing. Venera 13 gave us the first color panoramas of the surface in 1982.

The images show flat, jagged rocks and a sky that looks heavy. It’s oppressive. NASA often re-processes these old Soviet images using modern algorithms to sharpen the detail. It’s a rare moment of international space cooperation that’s lasted decades. You can see the landing struts of the probe in the corner of the frame, sitting on a bed of volcanic basalt. It stayed alive for 127 minutes. In that environment, that's a miracle.

The New Era: DAVINCI and VERITAS

We’ve had a bit of a drought lately. Most of our best images are old. But that’s changing.

NASA is currently prepping the DAVINCI mission. This is a "descent" mission. It’s basically a rugged sphere that will drop through the atmosphere, snapping high-resolution photos all the way down. For the first time, we’re going to get "human-eye" perspectives of the Alpha Regio highlands.

Then there's VERITAS. It’s going to give us a 3D map that’s so detailed we might finally see if the volcanoes are still erupting. Imagine a high-def video of a volcanic plume on a world where the air is as thick as water. That’s the goal.

Misconceptions About Color

People often get mad when they find out NASA images are "false color." They feel cheated.

"Why can't they just show us the real thing?"

The "real thing" is often invisible. If NASA only released true-color images, we’d have a library full of blurry white circles. By using false color to represent different wavelengths—like mapping sulfur density to green or heat to red—we learn about the planet’s soul. It’s data-driven art.

How to Find the Best High-Res Archives

If you want the raw, unedited files, don't just use a basic search engine. You have to go to the source.

- PDS (Planetary Data System): This is where the real nerds go. It’s NASA’s official repository for all mission data. It’s not "pretty," but it’s the raw truth.

- NASA Solar System Exploration Gallery: This is the curated stuff. It’s high-quality, includes captions, and is perfect for wallpapers.

- Kevin Gill’s Flickr: He’s a software engineer who does incredible unofficial processing of NASA data. His "re-imagined" Venus shots are often better than the official ones.

Looking at these images makes you realize how lucky we are on Earth. Venus is Earth’s "evil twin." It’s almost the same size. It’s made of the same stuff. But something went horribly wrong.

📖 Related: How Much Is an Apple PC: What Most People Get Wrong

Practical Steps for Exploring Venus Data

If you’re a student, an artist, or just a space fan, don't just look at the thumbnail.

- Check the metadata. Always see if the image is "Radar," "Infrared," or "Visible Light." It changes the whole context of what you're seeing.

- Look for the "limb." That’s the edge of the planet. In many NASA shots, you can see the thin, delicate layers of the atmosphere. It’s a reminder of how fragile a greenhouse effect can be.

- Compare years. Look at a Magellan radar map from 1990 and compare it to modern Pioneer Venus reconstructions. The jump in processing power is insane.

- Download TIFFs, not JPEGs. If you’re planning on printing or editing, NASA provides high-bitrate files that won't fall apart when you zoom in.

The mystery of Venus is hidden in its clouds. We’ve only seen a tiny fraction of the surface with our own "eyes." Every new image is a piece of a puzzle that might explain why Earth is a garden and Venus is a grave.

Next Steps for the Interested Observer:

Visit the NASA Planetary Photojournal and filter by "Image Addition Date" to see the most recent re-processed data from the Parker Solar Probe flybys. Many people don't realize that Parker, while heading to the Sun, recently captured some of the most stunning "night-side" images of Venusian surface features ever recorded in visible light—a feat previously thought impossible. Use the search term "WISPR Venus" to find these specific, groundbreaking frames.