You’ve probably tried it. You open Google Maps, switch to satellite view, and zoom into the vast, blue emptiness between California and Hawaii. You’re looking for a giant, swirling island of trash—a "Great Pacific Garbage Patch" that looks like a floating continent of plastic.

But you find nothing. Just blue.

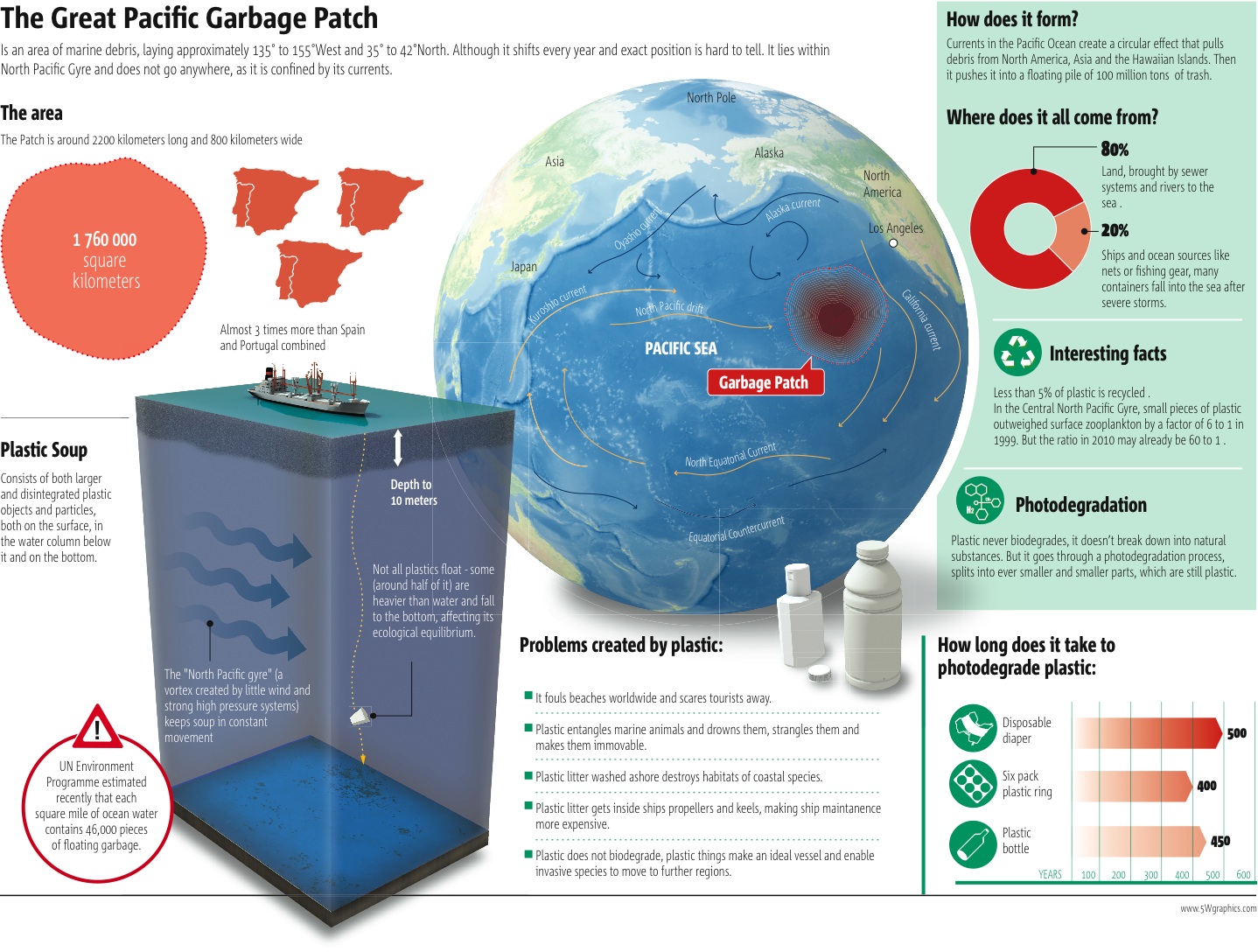

Honestly, it's frustrating. We've been told for decades that there is a trash heap twice the size of Texas out there, yet when we look for a satellite image of Pacific Garbage Patch clusters, the ocean looks pristine. This disconnect between what we hear and what we see is why so many people think the whole thing is a hoax, or at least a massive exaggeration. It isn't a hoax. It’s just that our eyes—and even our best satellites—aren't built to see what’s actually happening.

The "patch" isn't a solid mass. It’s more like a thin soup. Or a galaxy of plastic dust.

The resolution problem: Why satellites struggle

Most people expect a satellite image of Pacific Garbage Patch debris to look like a landfill floating on water. If you look at a satellite shot of a city, you can see cars, houses, and even individual trees. So why can’t we see the plastic?

The math is simple and kind of depressing. The vast majority of the plastic in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre is "microplastic." These are fragments smaller than 5 millimeters. Think of a grain of rice, then break it in half. Now, imagine billions of those grains scattered across millions of square miles of moving water. Even the highest-resolution commercial satellites, like Maxar’s WorldView-3, have a ground sample distance (GSD) of about 30 centimeters. That means one pixel on your screen represents a 30cm by 30cm square on Earth. A tiny shard of a laundry detergent bottle is literally invisible at that scale. It’s smaller than a single pixel.

Then there is the color.

Most of this plastic has been floating in the sun for years. It’s bleached. It’s translucent. It’s covered in "biofouling"—microscopic algae and barnacles that make the plastic match the color of the surrounding water. When light hits the ocean, the water absorbs most of the spectrum, leaving that deep indigo blue. The plastic just blends in. It doesn't pop.

What we actually see vs. what we expect

If you do find a "satellite image" online that shows a giant, neon-colored island of trash, it’s almost certainly a CGI render or a photo of a coastal harbor after a storm. Real researchers, like those at The Ocean Cleanup, don't just stare at Google Earth. They use specialized sensors.

💡 You might also like: How Many KB in a MB: The Answer Depends on Who You Ask

In 2016, a massive "Aerial Expedition" used a C-130 Hercules aircraft equipped with LiDAR and multispectral cameras. They weren't just taking "photos." They were measuring how light bounced off the surface.

Wait.

There is some big stuff. Ghost nets. These are discarded fishing nets that can be dozens of feet long. They weigh tons. Even then, from 500 miles up in space, a 10-meter fishing net is just a tiny, blurry speck that looks identical to a whitecap or a breaking wave. This is the "noise" problem. Satellites see millions of whitecaps every second. Distinguishing a white piece of plastic from a white bubble of foam is a nightmare for computer vision.

New tech is changing the game

We are getting better at this, though. Scientists are now using a technique called "hyperspectral imaging." Instead of just seeing Red, Green, and Blue (like our eyes), these sensors see hundreds of different wavelengths of light. Plastic has a specific "spectral signature." It reflects light in the short-wave infrared (SWIR) spectrum in a way that water doesn't.

A study published in Scientific Reports showed that researchers could use the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellites to spot "windrows" of trash. These are long lines of debris pushed together by currents. They look like streaks of light in specific infrared bands.

It’s not a "picture" in the traditional sense. It’s data.

The depth factor: It's not all on top

Here is something most people miss: the plastic isn't just on the surface.

Wind matters. A lot.

When the wind picks up, it creates turbulence that pushes the plastic down into the water column. Studies by researchers like Dr. Marcus Eriksen of the 5 Gyres Institute have shown that plastic can be found hundreds of meters deep. A satellite image of Pacific Garbage Patch areas can only see the top millimeter of the ocean. If it's a windy day, the patch "disappears" from view, even though it’s still right there, just five feet under the surface.

It’s a 3D problem being tracked with 2D tools.

Why this matters for the "Texas-Sized" myth

We often hear the patch is "twice the size of Texas." That’s a great headline, but it's misleading. It implies a boundary. It implies you could fly a plane and see where the trash starts and where it ends.

In reality, the concentration of plastic just gradually increases as you get toward the center of the gyre. In the "clean" ocean, you might find one piece of plastic every few miles. In the "patch," you might find hundreds of thousands of pieces in that same area. But it’s still mostly water. If you were swimming in the middle of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, you wouldn't feel like you were in a landfill. You would just see a few floating bits here and there.

It’s the sheer scale that’s the problem. It’s 1.6 million square kilometers of "soup."

Real-world data vs. viral photos

You’ve seen the photo of the turtle or the seahorse with the plastic straw. Those are real, and they are heartbreaking. But those photos are taken from boats or by divers. They are "ground truth" data.

When you see a news report using a satellite image of Pacific Garbage Patch regions, look closely at the caption. Most of the time, it will say "Visualisation" or "Model." These models are built using GPS-tracked buoys. Scientists toss hundreds of sensors into the ocean and watch where the currents take them. Over years, these buoys all cluster in the same five spots—the global gyres.

That’s how we map the patch. Not by seeing it, but by tracking how things move through it.

The business of cleaning it up

Organizations like The Ocean Cleanup, led by Boyan Slat, have shifted away from just "looking" for the patch to active extraction. Their System 03 is a massive, floating barrier that scoops up the larger debris before it can break down into those invisible microplastics.

They use satellite data to find "hotspots." They don't look for the plastic itself; they look for oceanographic features like eddies and fronts where plastic is likely to be trapped. It’s like a weather forecast for trash.

💡 You might also like: Did TikTok Just Get Banned? What Really Happened (Simply)

If they can catch a ghost net today, they are preventing a million pieces of microplastic from forming ten years from now.

Why can't we just use AI?

We are trying.

Machine learning is being trained to look at the Sentinel-2 data I mentioned earlier. The goal is to create an automated "trash alert" system. If the AI sees a spectral signature that looks like a high concentration of polyethylene, it can flag that coordinate for a cleanup ship.

But the ocean is big. Really big.

The Pacific Ocean covers about one-third of the planet's surface. Processing that much high-res satellite data every day is incredibly expensive. It’s a needle in a haystack, and the needle is the same color as the hay.

Actionable insights: What you can actually do

Since you can't just "see" the problem on a map, it’s easy to feel disconnected from it. But the data from those invisible satellite readings tells us exactly where the plastic is coming from.

- Stop the leak at the source. About 80% of ocean plastic comes from rivers. Supporting river-interception technology (like the "Interceptor" catamarans) is actually more effective than trying to skim the open ocean.

- Don't rely on "biodegradable" labels. Many of these plastics only break down in industrial composters, not in the cold, salty water of the Pacific. They just become smaller, more invisible pieces of the patch.

- Look for "Ground Truth" sources. If you want to see what the patch actually looks like, follow the NOAA Marine Debris Program or the Algalita Marine Research Foundation. They provide actual photos from expeditions rather than recycled CGI.

- Understand the "Invisible" impact. Just because a satellite image of Pacific Garbage Patch zones doesn't show a mountain of trash doesn't mean it isn't affecting the food chain. Microplastics absorb Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) like PCBs. Fish eat the plastic, and the toxins move up the chain to us.

The reality of the Pacific Garbage Patch is less like a floating island and more like a smog. You can't always see smog from a satellite photo of a city, but you sure as hell feel it when you're standing on the street. The ocean is the same way. We don't need a clearer picture to know we need to stop treating the Pacific like a giant, liquid rug we can sweep our mistakes under.

The next time you zoom in on Google Earth and see nothing but blue, remember: that’s exactly why it’s so dangerous. It’s a disaster that’s hiding in plain sight.

To get a better sense of the scale, you can track the real-time positions of cleanup vessels and research buoys through the NOAA Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS), which provides a much more accurate "image" of the ocean's health than any single photograph ever could.

👉 See also: Why Pictures of Mars Moons Still Look Like Lumpy Potatoes (And Why Scientists Love Them)

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

- Check the spectral data: Visit the European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel Online portal to see how multispectral imaging tracks ocean chlorophyll and debris.

- Support River Interception: Research the 1,000 most polluting rivers that contribute to the gyre and look into the technologies being deployed to stop plastic before it reaches the 12-mile limit.

- Audit Your Own Plastic Footprint: Use tools like the Plastic Footprint Network to see how much of your local waste is at risk of becoming "invisible" debris in the North Pacific.