You’ve probably seen the pictures. That eerie, glowing blue light emanating from a pool of water. It looks like something out of a sci-fi movie, but it's very real. It’s called Cherenkov radiation. Honestly, most people think the inside of a nuclear reactor is just a giant bomb waiting to go off, but the reality is much more like a very sophisticated, very hot tea kettle.

Physics is weird.

To understand what’s happening in there, you have to stop thinking about fire and start thinking about probability. Inside that massive steel pressure vessel, billions of atoms are splitting every single second. This isn’t a chemical reaction like burning coal. It’s nuclear. We are messing with the glue that holds reality together. When a neutron hits a Uranium-235 nucleus, the whole thing becomes unstable and splits. It releases heat, more neutrons, and a tiny bit of mass vanishes, converted directly into energy according to $E = mc^2$.

It's intense. It's crowded. And it's incredibly controlled.

The Pressure Vessel: A Giant Steel Thermos

The first thing you’d notice if you could shrink down and survive the radiation is the sheer scale of the containment. The reactor pressure vessel (RPV) is usually a massive steel cylinder, sometimes over six inches thick. It has to be. It’s holding back immense pressure—around 150 atmospheres in a Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR). That’s roughly 2,200 pounds per square inch.

Why so much pressure?

Simple: we need the water to get way hotter than 212°F without boiling. In a PWR, the water inside of a nuclear reactor stays liquid even at 600°F. If it turned to steam inside the core, it wouldn't be able to carry the heat away fast enough, and things would get messy. Fast.

The water serves two roles. It’s the coolant, obviously, but it’s also the "moderator." Neutrons flying off a split atom are moving way too fast to start another reaction. They’re like a golf ball moving at the speed of light—it’ll just zip right past the hole. The water molecules act like a bumper, slowing the neutrons down until they’re "thermal," which means they’re at the right speed to be captured by another Uranium atom.

The Fuel Rods and the Geometry of Power

The actual "magic" happens in the fuel assemblies. These aren't just blocks of metal. They are long, thin tubes made of a zirconium alloy. Zirconium is used because it’s basically "transparent" to neutrons; it doesn't soak them up and stop the party.

👉 See also: When Were Clocks First Invented: What Most People Get Wrong About Time

Inside these tubes are small ceramic pellets of Uranium dioxide. They’re about the size of a pencil eraser. One single pellet has as much energy as a ton of coal. Imagine that. A tiny ceramic cylinder holding that much potential. Thousands of these pellets are stacked into rods, and hundreds of rods are bundled into an assembly.

- A typical reactor might have 150 to 250 of these assemblies.

- They are arranged in a specific lattice pattern.

- The spacing is calculated down to the millimeter to ensure the neutron flux is even.

If you look at the inside of a nuclear reactor during operation, you’d see these assemblies glowing with heat. But you wouldn't see "fire." You’d see the water shimmering with convection currents.

Control Rods: The Brakes of the System

If the water is the gas pedal (by moderating neutrons), the control rods are the brakes. These are made of materials like Boron or Cadmium—elements that absolutely love to eat neutrons. When the operators want to slow things down, they drop these rods into the core.

The neutrons get absorbed by the Boron instead of hitting more Uranium. The chain reaction dies down. It’s a mechanical process. In many designs, like the Westinghouse PWRs common in the US, these rods are held up by electromagnets. If the power fails, the magnets turn off, and gravity simply drops the rods into the core. It’s called a "scram."

It’s a violent word for a very graceful safety feature.

Why the Blue Glow?

Let’s talk about that blue light. It’s not just for aesthetics. Cherenkov radiation happens when charged particles (like electrons) travel through a medium (like water) faster than the speed of light in 그 medium.

Wait. Nothing goes faster than light, right?

Correct, in a vacuum. But light slows down when it travels through water. These particles are moving faster than the "slowed down" light, creating a sort of electromagnetic "sonic boom." That’s the blue glow. It’s a signature of the inside of a nuclear reactor and spent fuel pools. It’s beautiful, but it’s a reminder of the sheer kinetic energy being shed by the fission products.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Gun to Head Stock Image is Becoming a Digital Relic

The Reality of Fission Products

As the Uranium splits, it doesn't just disappear. It turns into other elements—Xenon, Iodine, Cesium. These are the "fission products." Some of them are "neutron poisons."

Xenon-135 is the most famous one. It loves to soak up neutrons. After a reactor shuts down, Xenon builds up, making it hard to restart the reactor for a while. This is known as the "Xenon pit." Operators have to account for these shifting chemical balances every single hour. It’s a living, breathing chemical environment.

The fuel stays in the reactor for about 18 to 24 months. By the end of that time, the pellets have physically changed. They might be slightly swollen or cracked from the intense radiation bombardment. When they are removed, they are "spent," but they are still incredibly hot—both thermally and radiologically.

Myths vs. Reality

People think the inside of a nuclear reactor is a green, bubbling vat of liquid. Thanks, The Simpsons.

In reality, it’s remarkably clean. The water is purer than anything you’ve ever drunk. It has to be. Any impurities in the water would become radioactive as they pass through the neutron flux. This is called "activation." If there’s a speck of cobalt or iron in the water, it turns into a radioactive isotope, which then gets deposited in the pipes.

Everything is monitored. Every vibration. Every degree of temperature change.

What Happens When Things Go Wrong?

We have to talk about it. Meltdown.

A meltdown isn't a nuclear explosion. A nuclear reactor physically cannot explode like a Hiroshima-style bomb; the fuel isn't enriched enough. A meltdown is literally what it sounds like: the fuel gets so hot that it melts. If the water stops flowing, the decay heat (heat from the lingering radioactivity of those fission products) can melt the zirconium cladding and the ceramic pellets.

🔗 Read more: Who is Blue Origin and Why Should You Care About Bezos's Space Dream?

This creates a lava-like substance called "corium."

The goal of every safety system inside of a nuclear reactor is to keep the fuel covered in water. As long as there is water, the heat can be moved. Even if the fission reaction is stopped, that decay heat remains. It’s like a stove burner that stays hot long after you turn it off.

The Future: Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)

The "inside" is changing. New designs, like those from NuScale or TerraPower, are looking at different ways to manage the core.

Some don't use high-pressure water. They use liquid salt or liquid metal (like Sodium). Why? Because these liquids can get much hotter without boiling, and they don't require massive, thick pressure vessels. They are "passively safe," meaning they don't need pumps or electricity to stay cool if things go sideways.

Natural convection just takes over.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you're fascinated by what's going on inside these machines, there are a few ways to engage beyond just reading:

- Monitor Live Data: Some national grids, like the UK's or France's, provide real-time data on how much nuclear power is being fed into the grid. It’s a great way to see the "heartbeat" of a country's energy.

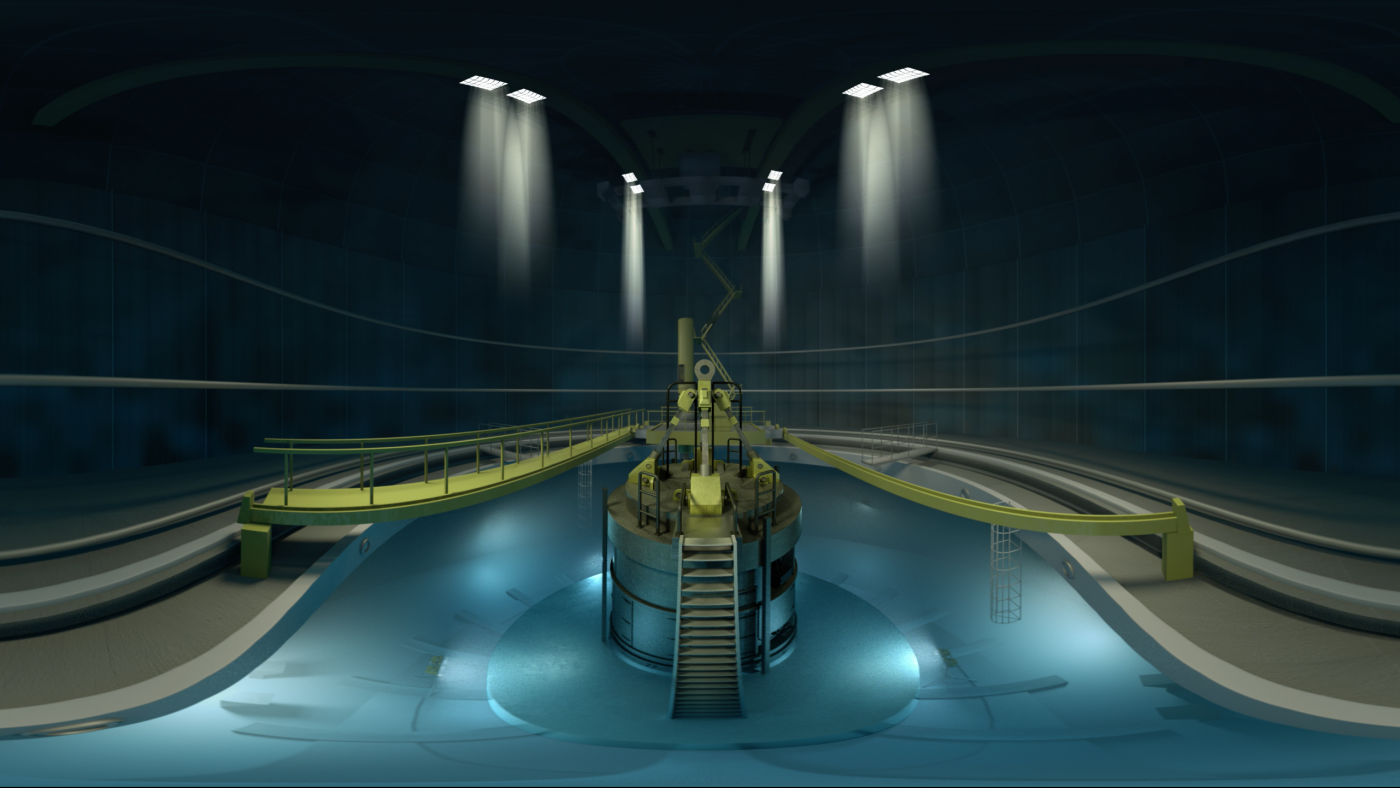

- Virtual Tours: Organizations like Idaho National Laboratory (INL) or the IAEA often offer high-resolution 360-degree virtual tours of reactor facilities. You can see the top of the reactor head and the cooling ponds.

- Track Policy: Keep an eye on the NRC (Nuclear Regulatory Commission) in the US. Their public records (ADAMS database) contain actual inspection reports of what’s happening inside specific reactors. It’s dense, but it’s the raw truth of nuclear operations.

- Understand the Fuel Cycle: Research "deep geological repositories." The story of the inside of a reactor doesn't end when the fuel is pulled out; the journey of those fuel rods lasts for ten thousand years.

The inside of a nuclear reactor is a triumph of engineering. It is a place where we have mastered the subatomic world to keep the lights on for millions of people. It is complex, slightly terrifying, and incredibly efficient. Understanding it is the first step toward having an honest conversation about our energy future.