You're looking at a schematic. It’s a mess of lines and zig-zags that looks like a caffeinated spider ran across the page. But then you spot it—the humble symbol for a wire. It's just a straight line, right? Well, mostly. Honestly, if you mess up how you draw or interpret that single line, your entire circuit board becomes an expensive paperweight. It’s the literal backbone of electrical engineering, yet people gloss over the nuances constantly.

Tracing a circuit isn't just about following the ink. It’s about understanding intent. When an engineer draws a line, they aren't just saying "put metal here." They are defining a path for electrons to flow, and depending on how that line intersects with others, the meaning changes entirely. You've got to know the difference between a connection and a jump, or you're going to end up with a short circuit that lets the "magic smoke" out of your components.

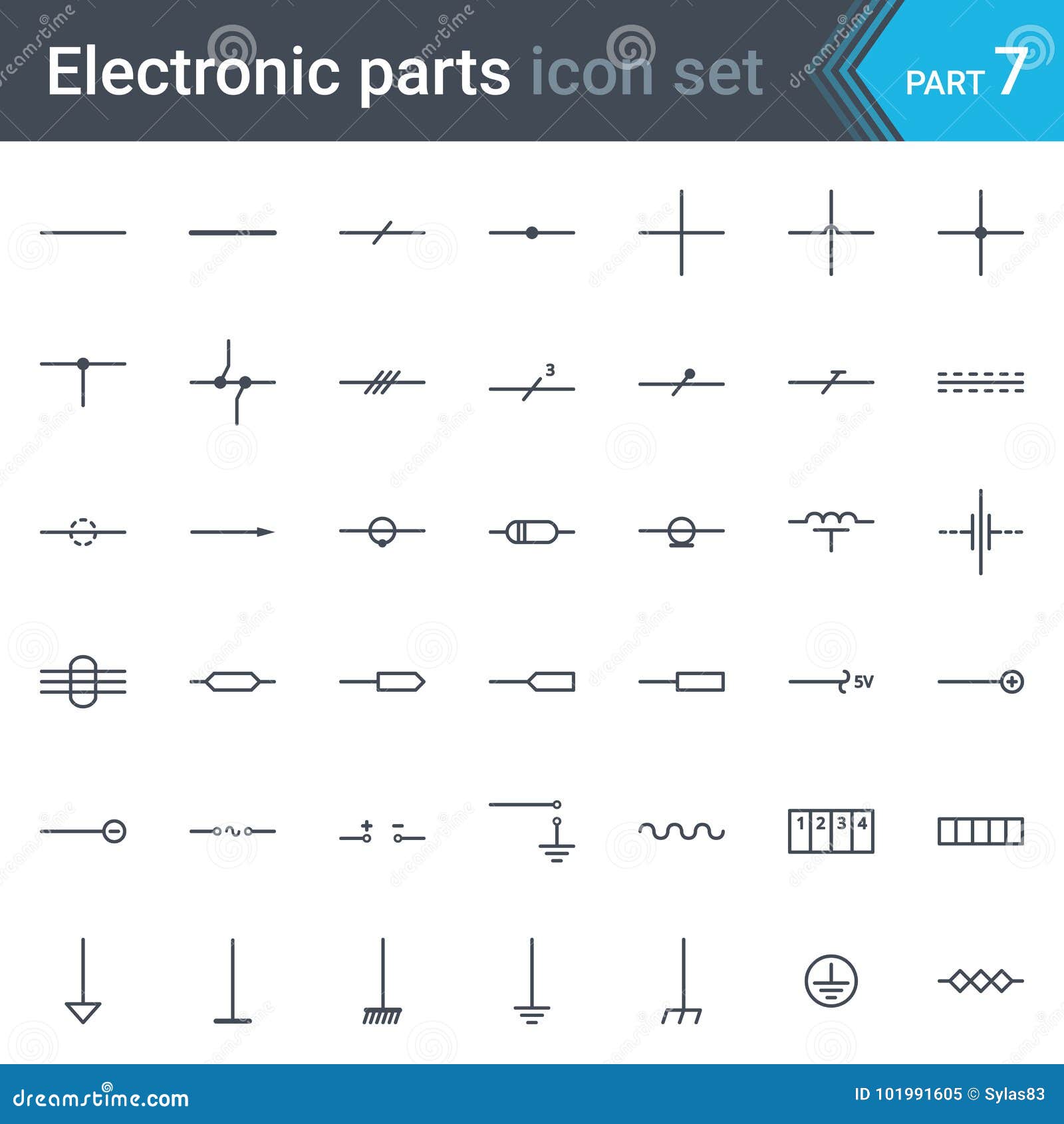

The basic line and its many moods

At its core, the symbol for a wire is a solid black line. Simple. But simplicity is deceptive in electronics. In the world of International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) standards or the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) styles, that line represents an ideal conductor. We assume it has zero resistance. In reality, every wire has some resistance, but for the sake of a drawing, we pretend it’s perfect.

Things get spicy when lines cross. This is where most beginners trip up. Back in the day, if two wires crossed but weren't supposed to touch, we used a little "hump" or a "bridge" symbol. It looked like a tiny hill. You’ll still see this in older hobbyist magazines or vintage radio schematics from the 1950s. Modern CAD software, like Altium or KiCad, has mostly moved away from the hump. Now, if two lines cross without a dot, they aren't touching. If there’s a big fat dot at the intersection? That’s a junction. They’re joined.

But wait. Some old-school diagrams use a system where a cross always means a connection, and you have to use the hump to show they don't touch. It’s a nightmare. This is why checking the legend of a schematic is the first thing any pro does. You can't just wing it. If you're looking at a European schematic versus one made in the States, the "language" of the lines might feel just a bit off-kilter.

Connections, junctions, and the dreaded dot

Let's talk about the "Node." When you see a symbol for a wire meeting another wire at a T-junction, it’s almost always a connection. Most standards don't even require a dot there because, logically, why would you draw a T if they weren't hitting each other? However, the four-way cross is the danger zone.

If you see four wires meeting like a plus sign, and there is no dot, they are passing over each other like ships in the night. If there is a dot, it’s a four-way junction. Most modern drafting standards actually discourage the four-way junction with a dot. Why? Because if the drawing is photocopied or printed poorly, that dot might disappear or look like a smudge. Pros prefer to stagger the junctions. You draw two separate T-junctions slightly apart. It’s clearer. It’s safer. It prevents your $5,000 prototype from exploding because of a printer error.

👉 See also: Vibe Coding With Claude Code: Why You Might Never Write A Line Of Syntax Again

When a wire isn't just a wire

Sometimes, the symbol for a wire needs to communicate more than just "electricity goes here." Think about shielded cables. If you're working with sensitive audio equipment or high-frequency data, a plain line won't cut it. You'll see a dashed line or a circle wrapped around the main wire line. This represents the shield—the braided metal that keeps out interference.

Then you have the "bus." A bus symbol is usually a much thicker line. It represents a whole bundle of wires traveling together. Imagine a highway versus a single-lane dirt road. On a schematic for a computer processor, you can't draw 64 individual lines for a data bus; the page would be unreadable. Instead, you draw one thick line and label it. It’s a shorthand that keeps engineers sane.

Grounding is another variation. Technically, the ground symbol is where the wire ends, but it's part of the wiring logic. You've got the "chassis ground" (the metal frame), the "earth ground" (a literal rod in the dirt), and the "signal ground." Each has a slightly different tail at the end of the wire line. Mixing these up is a classic rookie mistake that leads to "hum" in speakers or "noise" in sensors.

Real-world quirks and industry standards

If you're looking at a schematic for a Boeing 747, the symbol for a wire is going to be accompanied by a string of alphanumeric code. This is wire marking. Each line corresponds to a physical wire in a massive loom that might be miles long. In the aerospace world, the symbol is just a placeholder for a very specific gauge and material—often silver-plated copper with Tefzel insulation.

In contrast, a schematic for a simple guitar pedal might be hand-drawn. Here, the "wire" is often just a piece of 22 AWG solid core. The symbol is the same, but the physical reality is worlds apart. This is the nuance of E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness). An expert knows that the schematic is a map, not the terrain. You have to bring your own knowledge of physics to the table.

👉 See also: The Problem With ln ln x^2: Why Your Calculus Homework Feels Impossible

Navigating the confusion of "Crossing" vs. "Connecting"

- The Dot Method: A dot (also called a "node" or "junction") means the wires are electrically connected. No dot at a cross-over means no connection.

- The Bridge Method: A semi-circle "hump" means one wire is jumping over the other. This is rarely used in professional modern CAD but is common in educational materials.

- The Staggered Junction: Instead of a four-way cross, wires are offset. This is the gold standard for avoiding ambiguity.

Why does this keep changing?

Standards evolve because technology evolves. Back when we used vacuum tubes, wiring was point-to-point and messy. As we moved to Printed Circuit Boards (PCBs), the way we visualize traces—the flat "wires" on a board—had to become more disciplined. Today, we have "differential pairs"—two wires that must stay exactly the same distance apart to carry high-speed data like USB or HDMI. The symbol for these is two parallel lines often tied together with a bracket. If you don't respect that symbol's geometry on the physical board, the data will arrive garbled.

How to read schematics like a pro

Don't just stare at the lines. Look for the "nets." In modern design, every symbol for a wire is part of a "net"—a group of points that are all connected. Sometimes, a wire symbol will just end in a little flag or label like "VCC" or "+5V." This doesn't mean the wire goes nowhere. It means it's connected to every other point labeled "+5V" without having to draw a messy line across the whole page.

This "off-page" connector is a lifesaver. It keeps the diagram clean. Imagine trying to draw a wire from a power supply on page 1 to a sensor on page 50. It’s impossible. So, we use labels. It's still a wire; the symbol is just broken for the sake of legibility.

Putting it into practice

If you're building a project this weekend, or maybe you're just trying to fix a broken toaster, keep these things in mind.

- Check the style: Is it ANSI (square components) or IEC (more rectangular/rounded)? This tells you which "dialect" of symbol you're reading.

- Look for the dots: If you see a junction without a dot, be suspicious. Check other parts of the drawing to see if the author is consistent.

- Trace the power: Find the thickest lines or the ones labeled with voltages. These are your main "arteries."

- Respect the ground: Ensure all ground symbols eventually lead back to the same reference point, or you'll get ground loops.

Getting the symbol for a wire right isn't just about drawing straight lines. It's about clear communication. Electronics is a global language, and these symbols are the alphabet. Whether you're a DIYer using an Arduino or an engineer at NASA, that line is your primary tool for telling the story of how your invention works.

Next Steps for Accuracy

To ensure your circuit designs are professional and functional, your next move should be to download a standard symbol reference sheet. The IEEE Standard 315 or the IEC 60617 are the "dictionaries" of this world. While they can be dry, having them open while you work prevents the kind of fundamental errors that lead to hardware failure. Once you've mastered the wire, you can start looking into more complex symbols like MOSFETs and Op-Amps, where the lines start doing some truly heavy lifting.

Check your current schematic for any four-way intersections. If you find one with a dot, try redrawing it as two staggered T-junctions. It’s a small change, but it’s a hallmark of professional work that makes your designs much easier for others to read and trust. This is how you move from "playing with electronics" to actually "engineering" them. Keep your lines straight, your junctions clear, and your labels consistent. That is the secret to a circuit that actually works the first time you flip the switch.