You’re probably thinking about a bird. Most people do. They think of that clumsy, flightless pigeon-relative from Mauritius that became the universal mascot for failure. But David Quammen’s The Song of the Dodo isn't really a book about the dodo. Not specifically. It is a massive, sprawling, 600-page odyssey into why things die and, more importantly, where they die.

It’s about islands.

I first picked this up thinking it was a standard nature history. It isn't. It’s a detective story where the victim is biodiversity and the crime scene is always surrounded by water. Quammen spent eight years traveling to places like Madagascar, Guam, and the Aru Islands to track down a concept called island biogeography. It sounds academic. It sounds dry. Honestly, it’s anything but that because it explains exactly why our world is currently shattering into tiny, unsustainable pieces.

The Genius of Island Biogeography

Island biogeography is the "unified field theory" of conservation biology. It started with Robert MacArthur and E.O. Wilson back in the 1960s. Before them, people just thought islands were quirky places with weird animals. These two guys realized there was a mathematical relationship between the size of an island and the number of species it could hold.

Think of it like a hotel.

A small hotel has fewer rooms. Fewer rooms mean fewer guests. If a fire breaks out in a 4-room boutique hotel, everyone might die. If a fire breaks out in a 500-room Hilton, the "population" has a better chance of surviving. Islands work the same way. When a species is trapped on a small patch of land, any little hiccup—a drought, a new predator, a bad flu—can wipe them out forever.

📖 Related: Act Like an Angel Dress Like Crazy: The Secret Psychology of High-Contrast Style

Quammen takes this math and makes it visceral. He doesn't just talk about equations; he talks about the Komodo dragon. These giant lizards live on a handful of tiny islands in Indonesia. They are kings of their castle, but their castle is a prison. If the habitat shrinks by even a small percentage, the whole system collapses. This is the "song" Quammen is writing about. It’s the sound of a species thinning out until the last individual is wandering around alone, calling for a mate that doesn't exist.

Why the Dodo is a Red Herring

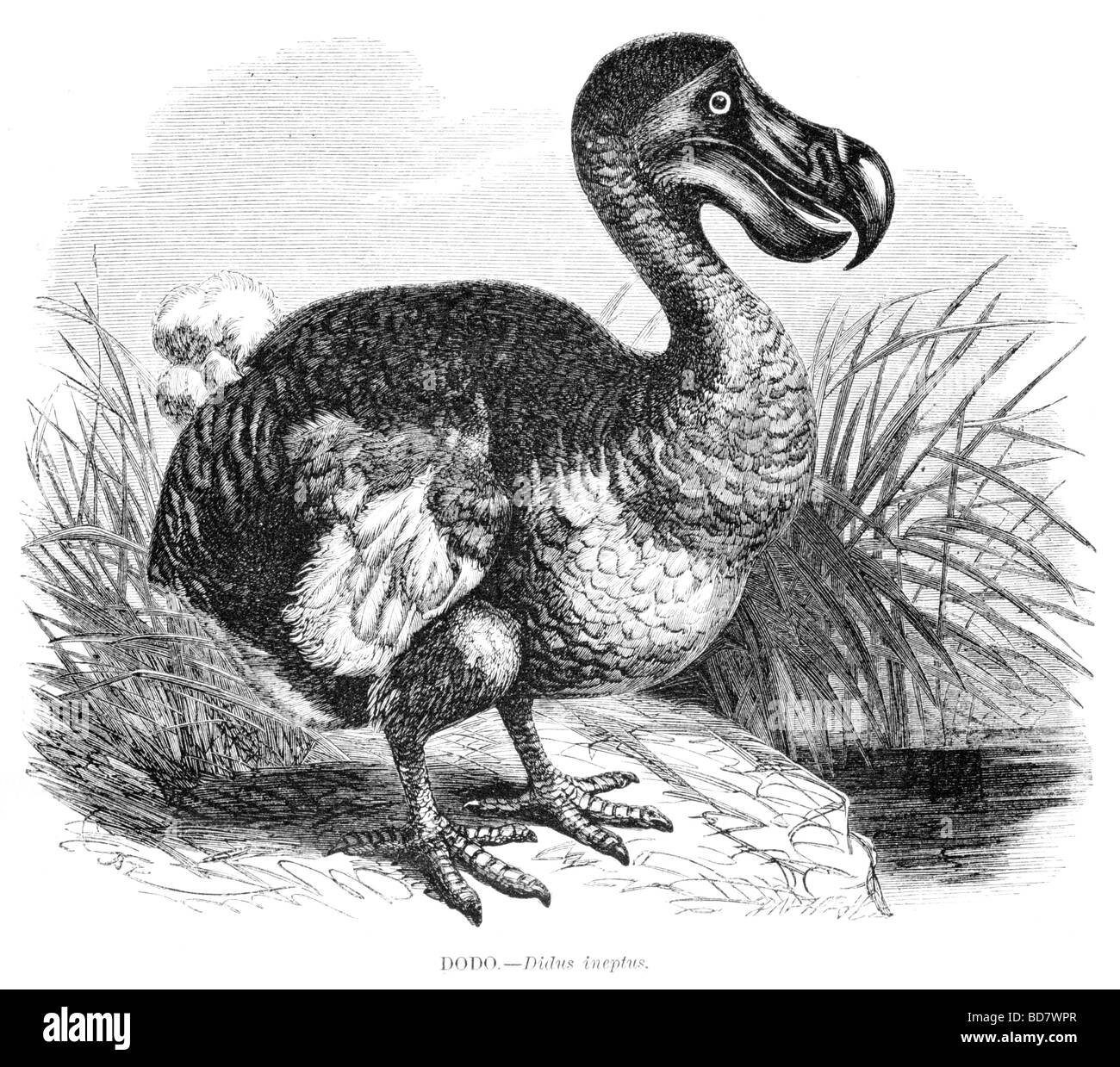

The dodo died out in the late 17th century. We all know that. But The Song of the Dodo uses the bird as a metaphor for "ecological naivety." On an island, predators are often non-existent. Evolution gets lazy. Or rather, evolution gets specialized. The dodo didn't need to fly because nothing was chasing it. Then humans showed up with pigs, rats, and monkeys.

The dodo wasn't stupid. It was just optimized for a world that no longer existed.

This is where the book gets scary. Quammen argues that we are turning the entire planet into a series of islands. When we build a highway through a forest, we create two islands. When we put a housing development in the middle of a grassland, we create a dozen islands. This is "habitat fragmentation." The animals inside these fragments are now subject to the same brutal math that killed the dodo. They are trapped. They can't migrate to find new food or new bloodlines.

We are "islandizing" the continents.

👉 See also: 61 Fahrenheit to Celsius: Why This Specific Number Matters More Than You Think

The Wallace Line and the Soul of the Book

A huge chunk of the narrative follows Alfred Russel Wallace. If you don't know Wallace, he’s the guy who basically co-discovered natural selection at the same time as Darwin but got half the credit and none of the fame. Quammen clearly has a soft spot for him.

Wallace was a "biogeographer" before the word existed. He noticed that in the Malay Archipelago, there’s an invisible line. On one side, the animals are Asian (monkeys, tigers). On the other, they are Australian (marsupials, cockatoos). Even though the islands are close together, the deep water between them kept the species separate for millions of years.

Quammen’s travelogue segments are some of the best prose in science writing. He’s trekking through jungles, sweating, getting bitten by insects, all to find the physical evidence of these invisible lines. He makes you care about things like the "trophic cascade" and "minimum viable population" because he ties them to the lived reality of the researchers on the ground.

He talks about the Brown Tree Snake in Guam. It was an accidental import that basically ate every bird on the island. Why? Because the birds didn't know they were supposed to be afraid. They were "naïve." Now, Guam is a silent forest. No birdsong. Just the rustle of millions of snakes in the canopy. It’s a haunting image that sticks with you long after you close the book.

Is it Too Depressing to Read?

People ask me if this book is just a long eulogy for the planet. Kinda. But it’s also an incredible adventure. Quammen is funny. He’s cynical. He’s deeply human. He talks about his own doubts and the quirks of the scientists he meets.

✨ Don't miss: 5 feet 8 inches in cm: Why This Specific Height Tricky to Calculate Exactly

The complexity is the point. Nature isn't a simple machine where you can just swap out parts. It’s a web. When you snip a thread, the whole thing sags. The Song of the Dodo teaches you how to see those threads. You’ll never look at a local park or a patch of woods behind a strip mall the same way again. You’ll see it for what it is: a tiny, struggling island.

Most science books from the mid-90s feel dated now. This one doesn't. If anything, it’s more relevant in 2026 than it was when it was published. We are seeing the "relaxation effect"—the delayed loss of species after habitat loss—happening in real-time across the Amazon and the American West.

The Actionable Reality of Island Life

So, what do we actually do with this information? Reading a 600-page book is great, but it has to change how we act. Quammen doesn't give a "10 Steps to Save the Earth" list because he knows it’s harder than that. But the science suggests a few clear paths.

- Corridors are everything. If you have two small forests, they are death traps. If you connect them with a "wildlife bridge" or a protected strip of land, you’ve effectively made one large island. Large islands have lower extinction rates.

- Size matters more than beauty. We often protect "scenic" areas that are actually ecological deserts. We need to prioritize large, contiguous chunks of "boring" habitat over small, disconnected "pretty" spots.

- Watch the edges. The "edge effect" is a killer. The perimeter of a forest is hotter, drier, and more prone to invasive species than the interior. A circular reserve is always better than a long, thin one because it has more "core" space.

If you want to understand the modern extinction crisis, you have to understand the math of islands. The Song of the Dodo is the manual for that math. It’s a long read, but it’s a necessary one. It’s the difference between knowing that species are dying and understanding why they don't have a choice.

Next Steps for the Curious Reader

To truly grasp the legacy of this book, you should start by looking at your own local geography through the lens of fragmentation. Open a satellite map of your town. Look for "islands" of green surrounded by asphalt.

- Identify Corridors: Check if your local government has any "Greenway" initiatives. These are often the only things preventing local extinctions of small mammals and birds.

- Support Land Trusts: Unlike large international charities, local land trusts often focus on buying small parcels of land specifically to connect existing protected areas. This is the "Island Biogeography" solution in action.

- Read Quammen’s Follow-ups: If 600 pages on birds and lizards felt like a breeze, move on to Spillover. It applies similar logic to how viruses "jump" from animal islands into human populations. It’s the natural evolution of his work on how we interact with the shrinking wild.

Nature isn't just "out there." It's being squeezed into smaller and smaller rooms. The song of the dodo is still playing; we just have to decide how much of the orchestra we’re willing to lose before we start expanding the stage.