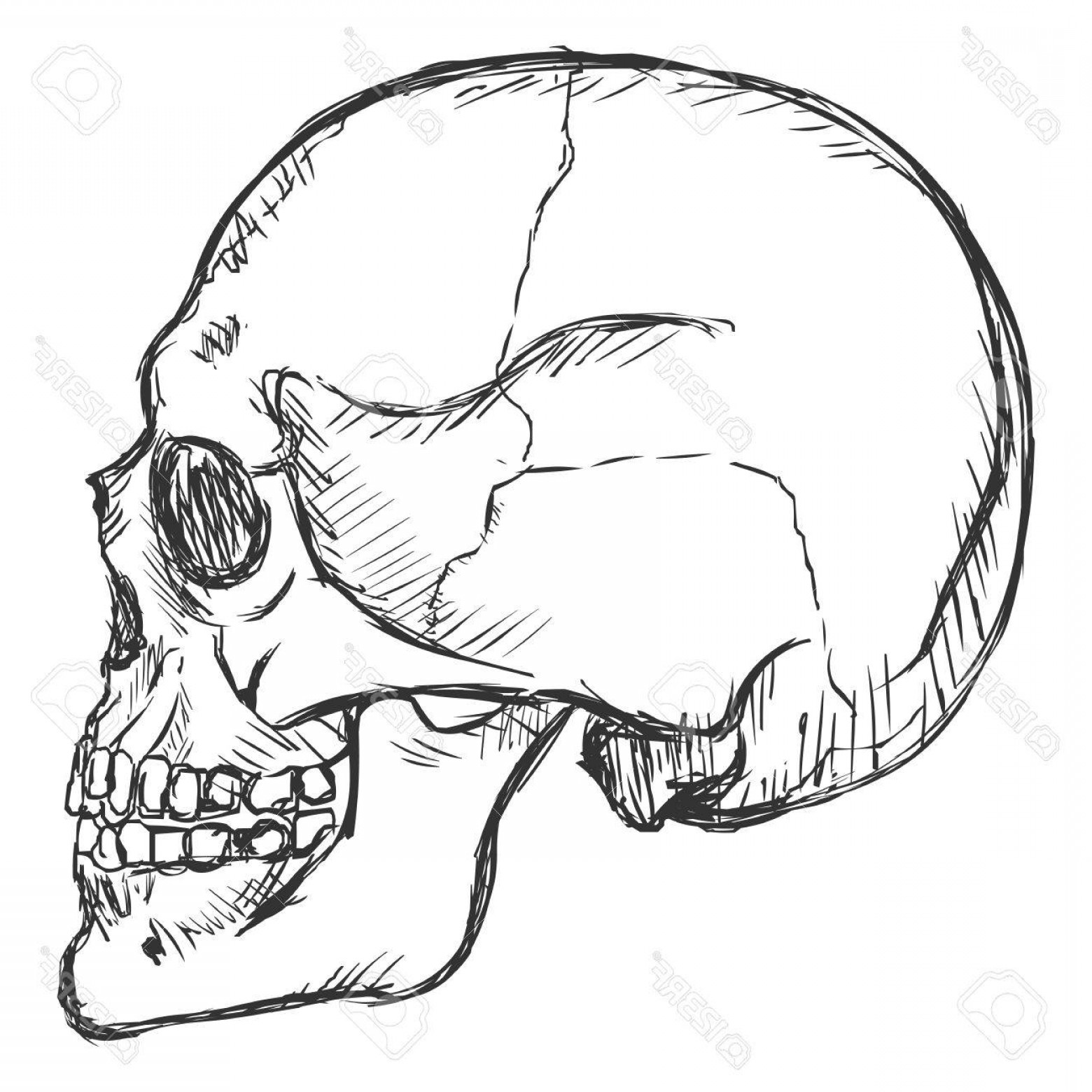

Look at a skull from the front and you see a mask. It’s the face we present to the world—the eyes, the teeth, the grin. But turn it ninety degrees. That side view of the skull, or what anatomists call the lateral aspect, is where the real engineering lives. It’s where the brain’s protective vault meets the heavy machinery of the jaw.

Honestly, most people ignore the lateral view because it looks like a complex puzzle of jagged lines. But if you’re trying to understand human evolution, forensic identification, or why your jaw clicks when you eat a bagel, this is the view that matters. It’s a map of high-stress junctions.

Every bump and groove has a job.

The Pterion: A Dangerous Convergence

There is a spot on the side of your head, roughly two fingers' width above your zygomatic arch, where four bones meet in an H-shaped junction. This is the pterion. It’s the weakest point of the skull. This is because the bone is remarkably thin here, acting as a structural "seam" between the frontal, parietal, temporal, and sphenoid bones.

Why does this matter for health? Because directly underneath this thin wall of bone sits the middle meningeal artery.

If you take a hard blow to the side of the head—think a baseball or a nasty fall—this is the spot that breaks. When the bone shatters, it often lacerates that artery. This leads to an epidural hematoma. It’s a medical emergency that can be fatal in hours because the pressure builds up so fast against the brain. Surgeons look at the side view of the skull specifically to map out this "temple" region before they ever pick up a scalpel. It’s high-stakes anatomy.

💡 You might also like: Foods to Eat to Prevent Gas: What Actually Works and Why You’re Doing It Wrong

Breaking Down the Lateral Landmarks

When you look at the skull from the side, the first thing that grabs your eye is the huge, sweeping curve of the neurocranium. This is the "brain box." It’s composed primarily of the parietal bone and the squamous part of the temporal bone.

The temporal bone is a weird one.

It looks like a flat plate, but it houses the most delicate equipment in your body: the inner ear. You can see the external acoustic meatus—that’s just the fancy name for your ear hole—sitting right behind the jaw joint. Just behind that hole is a chunky, blunt knob of bone called the mastoid process. If you feel behind your ear right now, you can touch it. That bump is hollow. It's filled with air cells, and its main job is providing a massive anchor point for the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which lets you turn your head to look over your shoulder.

The Zygomatic Arch: The Skull's Handlebars

Then you have the cheekbone. From the side, the zygomatic arch looks like a bridge. It literally bridges the face and the braincase. This arch isn't just for looks or holding up your sunglasses. It creates a gap.

Through that gap, the massive temporalis muscle slides down to attach to the jaw. When you clench your teeth, you can feel that muscle bulging on the side of your head. Without that specific architecture in the lateral view, you wouldn't be able to chew. The arch also protects the coronoid process of the mandible, acting like a roll cage on a race car.

📖 Related: Magnesio: Para qué sirve y cómo se toma sin tirar el dinero

The Jaw and the TMJ

The mandible, or lower bone, is the only moving part of the skull. From the side, it looks like an "L" shape. The vertical part is the ramus. At the top of that ramus is the condyle, which fits into the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone.

This is the Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ).

It is arguably the most complex joint in the human body. It doesn't just hinge; it slides. When you open your mouth wide, the bone actually pops out of its socket and slides forward onto a little bump called the articular tubercle. If that slide isn't smooth, you get that "click" or "pop" that drives people to the dentist. Seeing this from the side view of the skull makes it obvious why alignment is so finicky. Everything is packed into a space the size of a postage stamp.

Evolution Written in Bone

If you put a modern human skull next to a Neanderthal skull, the side view is where the differences scream at you.

Modern humans have a "globular" skull. It's round. High forehead. The side view of the skull shows a vertical front. Neanderthals, by contrast, had a "platycephalic" shape—their skulls were long and low, like a football. They had a massive bun of bone at the back called the occipital bun. We don't have that.

👉 See also: Why Having Sex in Bed Naked Might Be the Best Health Hack You Aren't Using

- The Forehead: Ours goes up; theirs went back.

- The Brow Ridge: From the side, a Neanderthal's brow looks like a porch roof. Ours is nearly flat.

- The Chin: Humans are the only primates with a true chin. If you look at the lateral view of a chimp or an early hominid, the jaw slants backward. Our jaw has a bony protrusion at the bottom that juts forward.

Anthropologists like Dr. Chris Stringer have used these lateral profiles to track how our brains expanded and our faces tucked themselves under our braincases over millions of years. It’s a story of "gracilization"—we got lighter, thinner, and more refined.

Forensic Insights and Age

Forensic artists rely on the side profile to reconstruct what a person looked like in life. The angle of the jaw, the prominence of the mastoid, and the depth of the orbits (eye sockets) are all visible from the side.

Age is another factor. In a newborn, the side view of the skull shows gaps. These are the fontanelles, or "soft spots." The most prominent one from the side is the sphenoidal fontanelle. As we age, these close, and the sutures—the wiggly lines where bones meet—slowly disappear. In a very old person, the sutures might be almost completely fused and invisible, making the skull look like one solid piece of ivory.

Clinical Reality: What This Means for You

Understanding this anatomy isn't just for people in lab coats. If you deal with chronic headaches, the side of your skull is often the culprit. Tension headaches often originate in the temporalis muscle (that big fan-shaped muscle on the side).

If you have sinus issues, the lateral view reveals the sphenoid sinus, tucked deep behind the eyes. It’s a "hidden" cavity that can cause deep, throbbing pain that feels like it's coming from the center of your head.

Actionable Insights for Better Health:

- Protect the Pterion: When playing contact sports, ensure your helmet specifically covers the temple area. Many "half-shell" helmets leave this thin-boned area exposed.

- Check Your Jaw: If you experience clicking in your TMJ, practice "tongue-up" resting positions. Placing your tongue on the roof of your mouth behind your front teeth helps keep the jaw in a neutral lateral alignment, reducing strain on the joint.

- Posture Matters: Because the mastoid process on the side of the skull is a primary anchor for neck muscles, "forward head posture" (looking at a phone) puts immense leverage on the lateral skull base. This is a common cause of cervicogenic headaches.

- Ear Health: The external auditory meatus is a direct tunnel toward the brain's base. Never use Q-tips deeply; the lateral view shows just how close the eardrum sits to the complex junctions of the temporal bone.

The side view of the skull is more than an anatomical diagram. It is a record of your ancestry, a map of your vulnerabilities, and a blueprint for how you interact with the world through eating, hearing, and thinking. By paying attention to these landmarks, you gain a better understanding of how your own body is built to survive.