Look at a map of Europe from 1988. It looks broken. A jagged, heavy line cuts right through the heart of the continent, turning one nation into two hostile experiments. This was the reality of the map of East Germany and West Germany, a geographic divorce that lasted forty years and, honestly, still hasn't fully healed.

History is messy.

If you grew up after 1990, the idea of two Germanys feels like a weird fever dream or a plot point from Bridge of Spies. But for decades, this wasn't just a "political situation." It was a physical wall. It was a fence. It was a minefield that separated cousins, coworkers, and lovers.

The Weird Geometry of the Inner German Border

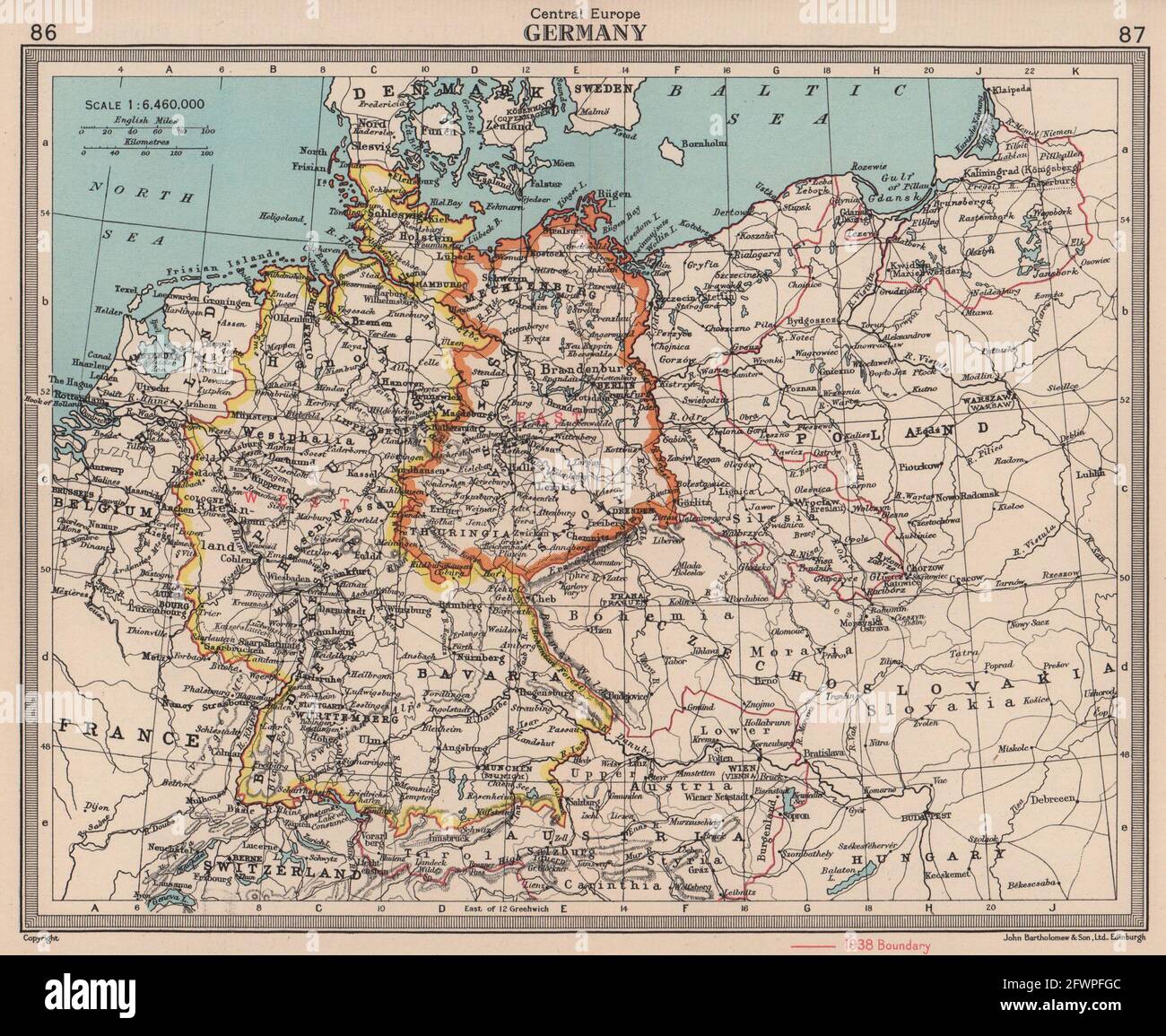

When we talk about the map of East Germany and West Germany, most people immediately think of the Berlin Wall. That's a mistake. The Wall was actually just a tiny, albeit famous, circular kink in the middle of East German territory. The real border—the Inner German Border—stretched nearly 860 miles from the Baltic Sea down to the Czechoslovakian border.

It wasn't a straight line. Not even close.

The border followed the old provincial boundaries of the German Reich as they existed in 1937, but with some brutal Cold War adjustments. It snaked through the Harz mountains, cut villages in half, and turned the Elbe river into a watery graveyard. Imagine living in a house where your front door is in the West, but your backyard is behind a barbed-wire fence in the East. That actually happened in places like Mödlareuth, a tiny village nicknamed "Little Berlin."

The Western side (the Federal Republic of Germany, or FRG) was roughly 96,000 square miles. The East (the German Democratic Republic, or GDR) was much smaller, about 41,000 square miles. Basically, the West was more than double the size of the East. This size difference mattered because it dictated everything from agricultural output to where people could hide.

Berlin: The Map’s Impossible Glitch

Berlin was a disaster for cartographers.

Technically, the entire city sat deep inside East German territory. It was an island. If you look at a map of East Germany and West Germany from the 1960s, West Berlin looks like a bright blue dot in a sea of red. To get there from West Germany, you had to take specific "transit corridors"—highways where you weren't allowed to stop, turn off, or even look too long at the scenery.

💡 You might also like: The Whip Inflation Now Button: Why This Odd 1974 Campaign Still Matters Today

If your car broke down on the transit road, you were in for a terrifying afternoon of Stasi interrogation.

The Berlin Wall didn't just divide the city; it encased West Berlin. It was a 96-mile loop. People often forget that the wall went all the way around the city, not just through the middle. It was a concrete prison for the people outside it, and a "freedom cage" for the people inside it.

Enclaves and Exclaves: The Steinstücken Mess

There were these weird little pockets of land called exclaves. Steinstücken was the most famous. It was a tiny patch of West Berlin territory located about a kilometer outside the city limits, entirely surrounded by East Germany. For years, the only way for the people living there to get to work was to be escorted by military police through East German territory. Eventually, the Allies had to build a paved road through "enemy" territory just to connect this tiny neighborhood to the rest of the city. Geography is rarely convenient.

Why the Border Looked the Way it Did

The map wasn't drawn by Germans. It was drawn by the victors of World War II at the Yalta and Potsdam conferences. The US, UK, and USSR basically took a marker to a map and carved out "zones of occupation."

- The British Zone: The Northwest (industrial heartland, Ruhr valley).

- The American Zone: The South (Bavaria, Hesse).

- The French Zone: The Southwest (Palatinate, Saarland).

- The Soviet Zone: Everything East of the Elbe.

By 1949, the three Western zones merged to form West Germany, while the Soviet zone became East Germany. This created a weird geopolitical imbalance. The West got the Rhine river and the industrial powerhouse of the Ruhr, while the East got the agricultural plains of Prussia and the cultural hub of Dresden.

The Economic Ghost on the Map

You can still see the map of East Germany and West Germany today. It’s invisible, but it’s there.

If you look at a map of average household income in Germany in 2024, the old border reappears. The East is poorer. If you look at a map of where the major DAX companies (the German stock market giants like Siemens or BMW) are headquartered, they are almost all in the West. When the wall fell, the East's industry basically collapsed overnight because it couldn't compete with Western efficiency.

Even the lights are different.

📖 Related: The Station Nightclub Fire and Great White: Why It’s Still the Hardest Lesson in Rock History

Astronauts have taken photos from the International Space Station showing Berlin at night. You can still see where the East ends and the West begins because the East used sodium-vapor lamps (which look yellow) while the West used fluorescent and LED lights (which look white or blue). The map is literally written in light.

Religious and Social Fault Lines

It's not just money. The map of East Germany and West Germany tracks with how people think.

The East is one of the most atheistic regions in the entire world. Forty years of state-sponsored "Scientific Atheism" under the SED (the ruling party of the GDR) effectively broke the back of the church. In the West, especially in Bavaria, Catholicism remains a massive cultural pillar.

Then there’s the voting.

In recent years, the rise of the AfD (Alternative for Germany) party has almost perfectly mapped onto the old borders of the GDR. Why? Some sociologists, like Steffen Mau, argue that the "East German identity" was forged in opposition to the West, and that sense of being "second-class citizens" didn't vanish just because the fences did. The map is a psychological scar.

Specific Landmarks You Can Still Visit

If you want to feel the weight of this history, you have to go to the "Green Belt."

Because the border was a "no-man's land" for forty years, nature took over. Rare birds, insects, and plants that were dying out elsewhere thrived in the death strip because no humans were allowed to walk there. Today, that old border is a massive nature preserve.

- Point Alpha: Located between Hesse and Thuringia, this was the "hottest" spot of the Cold War. It was where NATO expected the Soviet Union to invade through the Fulda Gap.

- The Elbe River: In some places, the border ran right down the middle of the river. West German fishermen and East German border guards used to play a tense game of "don't cross the line" every single day.

- Brocken Mountain: The highest peak in the Harz mountains. It was covered in listening posts. The Stasi and the Soviets used it to spy on radio traffic deep into West Germany.

How to Read a Modern German Map

When you look at a map of Germany now, don't just look at the state lines. Look at the infrastructure.

👉 See also: The Night the Mountain Fell: What Really Happened During the Big Thompson Flood 1976

Notice the rail lines. Many of the tracks that used to connect East and West were torn up by the Soviets as "reparations" after WWII or simply blocked during the Cold War. Even now, the high-speed ICE train network is much denser in the West.

Look at the demographics. The East is older. After the Reunification in 1990, millions of young people—especially women—fled the East for jobs in Munich, Hamburg, and Frankfurt. This created a "demographic hole" in the former GDR that town planners are still trying to figure out how to fix.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you’re trying to understand or visit the remnants of the map of East Germany and West Germany, here is how to do it right:

First, don't just stay in Berlin. Berlin is its own weird microcosm. To see what the division actually did to the country, go to the Thuringian Forest or the Harz mountains. Visit the Borderland Museum Eichsfeld. It’s one of the few places where you can see the layers of fences, the bunkers, and the watchtowers in their original context.

Second, use the "Traffic Light Man" test. If you're walking in a German city and the little guy on the walk signal is wearing a hat (the Ampelmännchen), you are in the former East. If he’s a generic stick figure, you’re in the West. It is the most consistent piece of cartography left.

Third, look at the farm sizes. If you're flying over Germany, the East has massive, sweeping fields. This is a relic of the "collectivization" era where the communists seized private land to create giant state farms. In the West, the fields are smaller and more fragmented, reflecting centuries of family ownership.

The map of East Germany and West Germany isn't just a relic of the past. It's a layer of DNA underneath the modern country. You can't understand Europe's economy, its politics, or its anxieties without realizing that for half a century, "Germany" was two different worlds sharing one very long, very dangerous fence.

To truly see the remnants of the division, download a GPS-based overlay map like the ones provided by the German Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb). These maps allow you to walk through modern cities while seeing exactly where the "Death Strip" used to be. For a deep dive into the specific geographic anomalies, check out the archives at the Stasi Records Agency (BStU), which detail exactly how the border was surveilled and maintained down to the meter. Reality on the ground often tells a much harsher story than the clean lines on a printed map.