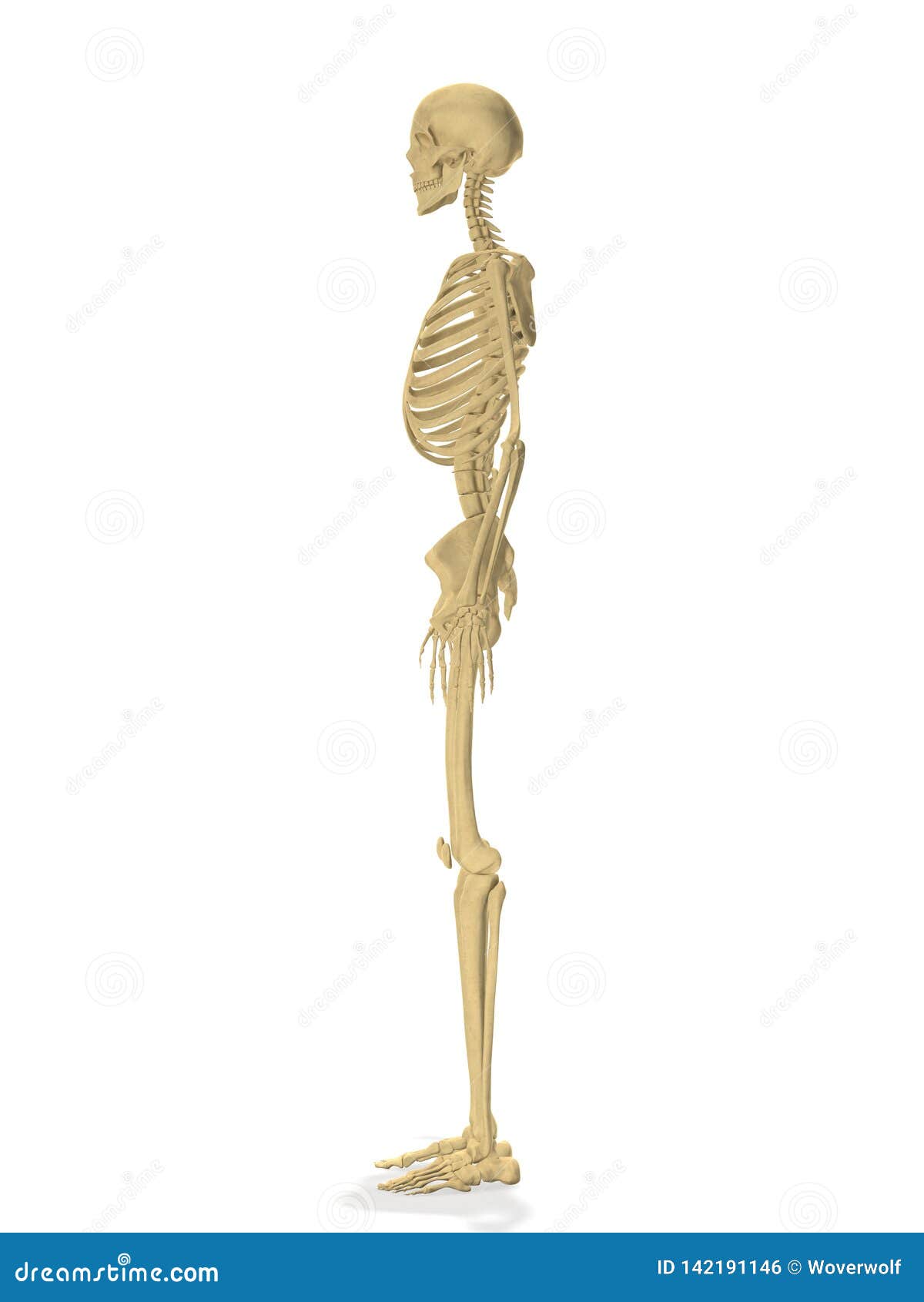

Ever stood behind one of those plastic medical models in a doctor’s office and just stared? Most of us focus on the "face" of the skeleton—the grinning skull, the ribs, the hip bones that look like butterfly wings. But honestly, the back view of the skeleton is where all the real drama happens. It’s where your history of sitting at a desk, your lifting habits, and even your breathing patterns are written in bone. If the front of the skeleton is the storefront, the back is the engine room. It’s dense. It’s complicated. And it’s arguably the most important perspective for understanding why our bodies hold up—or fall apart—the way they do.

People usually search for a rear view because they’re trying to visualize a "pinched nerve" or see exactly where that nagging knot in their shoulder blade sits. What they find is a masterpiece of engineering. From the base of the occipital bone down to the tiny, often-forgotten coccyx, the posterior view reveals a structural stability that the front simply can’t match.

The Spine: That Gnarly Central Pillar

When you look at the back view of the skeleton, the first thing that hits you is the vertebral column. It’s not just a straight rod. If it were, you’d walk like a robot and shatter your vertebrae every time you jumped. It has these subtle, elegant curves. From the rear, though, it should look straight. If it leans or snakes to one side, you’re looking at scoliosis, a condition that affects roughly 3% of the population, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

The posterior view is the only way to truly see the spinous processes. These are those little bumps you feel when you run your thumb down someone’s back. They aren't just for show; they act as massive lever arms for the muscles that keep you upright. Each vertebra is a chunky piece of bone, but as you move from the cervical (neck) down to the lumbar (lower back), they get beefier. By the time you hit the L5 vertebra, that bone is thick enough to support the weight of your entire upper torso. It’s basically the foundation of a skyscraper.

Interestingly, the holes you see in the back view—the intervertebral foramina—are where the spinal nerves exit. When a doctor talks about a herniated disc "hitting a nerve," they are looking at this specific posterior-lateral geography. It’s tight in there. There isn't much room for error.

👉 See also: Magnesio: Para qué sirve y cómo se toma sin tirar el dinero

The Scapula: The Floating Mystery

Now, look at the shoulder blades. Formally called the scapulae, these bones are weird. They don't actually bolt onto the ribs. They "float" in a sea of muscle and connective tissue. From the back view of the skeleton, you can see the "spine of the scapula," which is that prominent ridge running across the top. This is the anchor point for the deltoids and the trapezius.

The scapula is basically a giant mechanical pulley. Because it isn't fused to the ribcage (unlike the way the pelvis is fused to the spine), it allows your arm to move in almost a full circle. But this freedom comes at a cost. Since it’s held in place by muscle rather than bone-on-bone contact, it’s prone to "winging." If you've ever seen someone’s shoulder blade poke out like a bird's wing, that’s usually a sign of a weak serratus anterior muscle. From a posterior perspective, it’s glaringly obvious.

The Pelvic Powerhouse

Lower down, the back view of the skeleton shows the sacrum and the ilium coming together at the sacroiliac (SI) joints. This is a common "pain point" for athletes and pregnant women. Unlike the hip joint, which is a ball-and-socket and moves a lot, the SI joint is meant to stay relatively still. It’s a shock absorber. It transfers the weight of your spine into your legs.

The back of the pelvis also features the ischial tuberosity. You know those "sit bones" that hurt after a long bike ride or sitting on a hard bleacher? That’s them. They are the lowest part of your pelvis. From the rear, you can see how they provide a stable base for the hamstrings to attach. It’s a rugged, thick area of bone designed to handle high-tension forces. If you’re a runner, this is the area that’s constantly being tugged on every time your foot hits the pavement.

✨ Don't miss: Why Having Sex in Bed Naked Might Be the Best Health Hack You Aren't Using

Why Artists and Doctors Obsess Over This Angle

Medical illustrators like Frank Netter or the creators of the classic Gray’s Anatomy spent an incredible amount of time perfecting the posterior view because it’s the most "honest" look at the body. The front is obscured by the rib cage and the soft organs of the belly. The back is pure structure.

For a physical therapist, the back view of the skeleton is a diagnostic map. They look at the height of the iliac crests (the top of the hips). If one is higher than the other, your legs might be different lengths, or your pelvis is tilted. They look at the space between the spine and the scapula. Too wide? Your back muscles are likely overstretched and weak. Too narrow? You’re probably hunched over a laptop for ten hours a day.

Bone Density and the "Dowager’s Hump"

One of the more sobering things you see in a posterior-lateral view is the onset of kyphosis. While we often think of bones as static, they are living tissue. They react to stress. When someone develops osteoporosis, the front of the vertebrae can collapse, causing the spine to curve forward. From the back, this creates a visible hump. This isn't just "bad posture"—it’s a structural change in the bone itself. Dr. Susan Ott from the University of Washington has done extensive work on bone remodeling, and the back of the skeleton is where these changes are most visible to the naked eye. It’s a reminder that what we do today—how we eat, how we lift, how we move—literally shapes the mineralized cage we live in.

Common Misconceptions About the Rear View

People often think the ribs are a solid wall. They aren't. From the back, you can see the gaps clearly. These gaps, the intercostal spaces, allow your lungs to expand. If your ribs were a solid plate of bone, you’d suffocate. Also, many people assume the tailbone (coccyx) is a single bone. It’s actually three to five small, fused segments. From the back view of the skeleton, it looks like a tiny, curved beak tucked under the sacrum. It’s small, but if you’ve ever fallen on the ice and bruised it, you know it’s arguably the most sensitive part of the whole rig.

🔗 Read more: Why PMS Food Cravings Are So Intense and What You Can Actually Do About Them

Another myth is that the spine is supposed to be perfectly straight when viewed from the side. Nope. You need those lordotic and kyphotic curves to act as springs. However, from the direct back view, straightness is the goal. Any deviation from that vertical plumb line usually means the muscles are pulling unevenly, or the bones have adapted to an asymmetrical lifestyle.

Actionable Insights: Taking Care of Your "Rear View"

Understanding the back view of the skeleton isn't just for anatomy nerds. It has real-world applications for how you treat your body. If you want to keep your skeletal system healthy, you have to think about the posterior chain.

- Move your scapulae: Most of us keep our shoulder blades frozen. Practice "scapular retractions"—basically squeezing your blades together as if you're trying to hold a pencil between them. This keeps the joints mobile and prevents the "slumped" look.

- Watch your seat: Since those ischial tuberosities (sit bones) take the brunt of your weight, invest in a chair that supports the natural curve of your lumbar spine. If you feel pressure on your sacrum, you’re slouching too far back.

- Strengthen the "Anti-Gravity" muscles: The muscles that attach to the back of your skeleton—the erector spinae, the glutes, the hamstrings—are what keep you from folding like a lawn chair. Deadlifts (with proper form!) and rows are essentially maintenance for your skeleton.

- Check your alignment: Stand with your back against a flat wall. Your heels, your butt, your shoulder blades, and the back of your head should ideally touch the wall without you having to strain. If your head is inches away from the wall, your cervical spine is under massive stress.

The skeleton isn't just a spooky decoration for Halloween. It’s a dynamic, changing framework. When you look at the back view of the skeleton, you’re looking at the support system that allows you to walk, twist, and stand tall. It’s worth taking care of.

Next time you see a diagram of the human frame, flip it around. Look at the way the ribs tuck into the thoracic vertebrae. Notice the way the pelvis cradles the base of the spine. There’s a rugged beauty in that posterior symmetry. It’s the silent partner in every move you make, holding everything together while the rest of you faces the world.

Practical Next Steps

- Perform a "wall test" today to see if your posterior alignment is neutral or if you've developed a forward-head lean.

- Focus on "pull" exercises in the gym (rows, pull-ups, face pulls) to strengthen the muscles that support the scapula and posterior spine.

- Consult a professional if you notice a visible "S" curve or uneven hip height when looking at your reflection in a rear-view mirror setup.