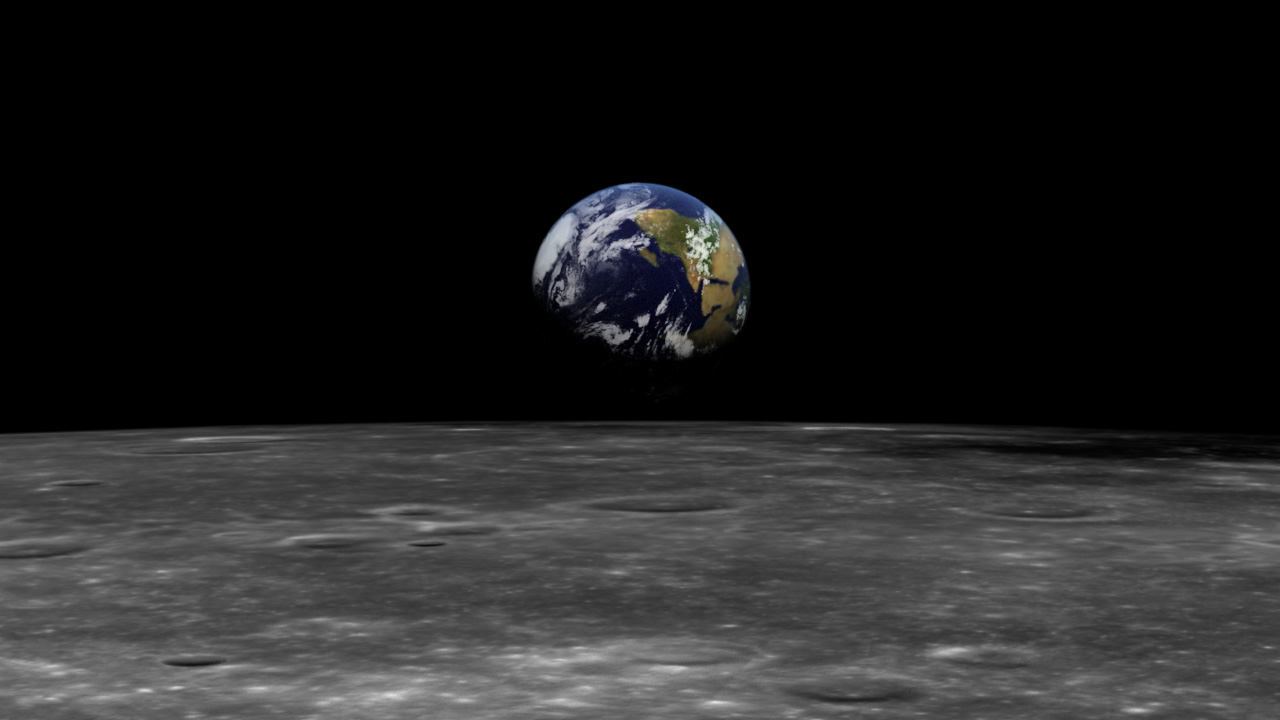

Look at it. Really look at it. You’ve seen it on t-shirts, stamps, and textbook covers since you were a kid, but the Apollo 17 earth photo, famously known as "The Blue Marble," is weirder and more significant than most people realize. It wasn’t just a lucky snapshot taken by a bored astronaut on his way to the moon. It was a technical fluke, a cultural reset, and honestly, a bit of a spatial mind-bender that almost didn't happen the way we remember it.

The image was captured on December 7, 1972. The crew of the Apollo 17 mission—Eugene Cernan, Ronald Evans, and Harrison Schmitt—were about 28,000 miles away from home. At that specific distance, the sun was directly behind the spacecraft. This is a big deal because it meant the entire Earth was fully illuminated. Most space photos show a "crescent" Earth or have part of the planet shrouded in shadow. Not this one. This was a glowing, fragile glass marble hanging in a total void. It was perfect.

The Logistics of the Famous Apollo 17 Earth Photo

Taking a photo in space in 1972 wasn't like pulling out an iPhone 16. The astronauts were using a Hasselblad 500EL camera with a 80mm Zeiss lens. There was no viewfinder. They were basically "point and shooting" into a vacuum while moving at thousands of miles per hour.

Schmitt, Cernan, and Evans all have a claim to the shot, but NASA officially credits the crew as a whole. History suggests Harrison "Jack" Schmitt was likely the one behind the lens for the most famous version. He was a geologist, the only actual scientist to ever walk on the lunar surface, so he had a natural eye for the "specimen" that is our planet.

What's kinda funny is that the original photo was technically "upside down" based on traditional map orientations. In the raw film, Antarctica is at the top. NASA flipped it before releasing it to the public because they figured people would get confused if the South Pole was "up."

The Gear That Made It Possible

The Hasselblad was a beast. It used 70mm film, which is roughly four times the size of standard 35mm film. This is why the Apollo 17 earth photo has such insane detail even when it's blown up to the size of a billboard. You can see the Cyclone in the Indian Ocean. You can see the Transantarctic Mountains. You can see the actual weather patterns of a specific Tuesday in December 1972.

🔗 Read more: Powers Electric A Type: Why This Forgotten EV Startup Still Matters

Why This Image Killed the Space Race (In a Good Way)

By the time Apollo 17 rolled around, the public was honestly getting a little bored of the Moon. We’d been there. We’d played golf. We’d driven the rover. The "Space Race" was technically won, and the budget for NASA was getting slashed.

But when this photo hit the newspapers, the conversation shifted. It wasn't about the Moon anymore. It was about us.

The Apollo 17 earth photo became the face of the emerging environmental movement. It’s hard to argue that resources are infinite when you’re looking at a tiny, lonely ball of blue and white surrounded by an infinite, pitch-black nothingness. It made the planet look small. It made it look finish-able.

The "Overview Effect"

Psychologists and astronauts talk about something called the "Overview Effect." It’s this cognitive shift that happens when you see the Earth from orbit. You stop seeing borders. You stop seeing "us vs. them." You just see a biological system trying to survive.

The Blue Marble gave that feeling to people who would never leave the atmosphere. It was the first time humanity saw its home as a single, unified object. Before this, most "Earth-rise" photos from Apollo 8 showed the Moon's surface in the foreground, which grounded the viewer's perspective on another celestial body. The Apollo 17 shot was different because the Earth stood alone.

Technical Specs and the 70mm Magic

If you’re a photography nerd, the specs on this shot are a dream.

- Camera: Hasselblad 500EL (modified for NASA)

- Film: 70mm Ektachrome

- Aperture: f/11 (roughly)

- Shutter Speed: 1/250th of a second

The clarity comes from the lack of an atmosphere. On Earth, we have to deal with haze, dust, and humidity. In the vacuum between the Earth and the Moon, there is nothing to scatter the light. The photons hitting that Ektachrome film were pure, unadulterated sunlight bouncing off the Indian Ocean.

Common Myths About the Blue Marble

People love a good conspiracy, and the Apollo 17 earth photo has plenty of them.

First, there’s the "it’s a composite" crowd. Today, most NASA "Blue Marble" images (like the ones from 2012) are indeed composites. They take strips of data from satellites and stitch them together because most satellites orbit too close to the Earth to see the whole thing at once. But the 1972 photo? That’s a single frame. It’s a real, physical piece of film that was developed in a lab.

Second, some people think it was staged in a studio. Honestly, if you look at the cloud patterns and compare them to the meteorological data from 1972, the "faking" it would have been harder than actually going to the Moon. The cyclone visible in the bottom right of the image was a real storm tracked by weather stations at the time.

The Cultural Legacy

It's one of the most distributed images in human history. It showed up on the first Earth Day posters. It’s been used by everyone from Al Gore to Apple. It basically defined the 1970s "Save the Planet" aesthetic.

But there is a bit of a tragedy to it. This was the last time a human being was far enough away from Earth to take a photo like this. Since 1972, no human has traveled beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO). When astronauts on the International Space Station take photos, they are only about 250 miles up. They can see the curve of the Earth, but they can't see the "Marble." To see the whole circle, you have to be tens of thousands of miles away.

We haven't seen our home with our own eyes like that in over 50 years.

💡 You might also like: Where Was the Atomic Bomb Tested? The Real Story of Ground Zero

How to View the Original Today

You don't have to settle for a grainy JPEG. NASA has high-resolution scans of the original film available in their archives.

- Search the NASA Image and Video Library: Look for ID "AS17-148-22727."

- Look for the "Raw" versions: Many sites apply heavy saturation or filters. The original has a slightly more muted, realistic color palette that is actually more haunting.

- Check the metadata: If you find a version where you can see the sprocket holes of the film, you're looking at a scan of the full transparency.

What This Photo Means for the Future

As we look toward the Artemis missions and a return to the Moon, we are probably going to get a "New Blue Marble." With modern 8K digital sensors, the detail will be staggering. We’ll be able to zoom in on individual cities from the Moon.

But will it have the same impact? Probably not. The 1972 Apollo 17 earth photo hit a world that had never seen itself before. We were a species with amnesia about our own scale, and that photo was a mirror held up to our faces.

Actionable Steps for the Curious

If you want to really appreciate this piece of history, don't just scroll past it.

- Download the TIFF: Go to the NASA archives and download the uncompressed TIFF file of AS17-148-22727. Zoom in until you see the grain of the film.

- Compare it to 2026 satellite imagery: Look at how the ice caps in the 1972 photo compare to current satellite views from the DSCOVR: EPIC camera. It’s a sobering lesson in climate change.

- Read the transcript: Look up the Apollo 17 flight journal for "Ground Elapsed Time" 05:05:00. You can read the actual conversation between the astronauts as they realized what they were seeing. They weren't talking about "greatness." They were mostly arguing about who had the camera and trying to make sure the exposure was right so they didn't blow out the highlights.

The Blue Marble isn't just a picture. It's a timestamp. It marks the exact moment humanity looked back and realized that for all our noise and conflict, we're all just riding on a very small, very wet rock in a very large dark room. That perspective is worth keeping, especially now.

👉 See also: DJI 360 Camera Release Date: Why the Osmo 360 Changes Everything

To dig deeper into the actual science of how this photo was developed and the specific chemistry of the Ektachrome film used in 1972, you can research the Kodak 70mm MS (Medium Speed) film specs which were custom-made for the vacuum of space. Understanding the radiation shielding required for that film helps you appreciate just how miraculous it is that the image survived the trip back through the atmosphere at all. Check the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s online collection for a look at the actual camera body used on the mission; it’s a masterclass in ruggedized engineering.