It happened over a century ago. The date was April 15, 1912. Yet, we are still obsessed with the physics of that freezing night in the North Atlantic. Most people think they know what happened because they saw James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster, but modern simulation of the titanic sinking has actually proven that Hollywood got some pretty big things wrong.

Actually, it’s not just about the movies.

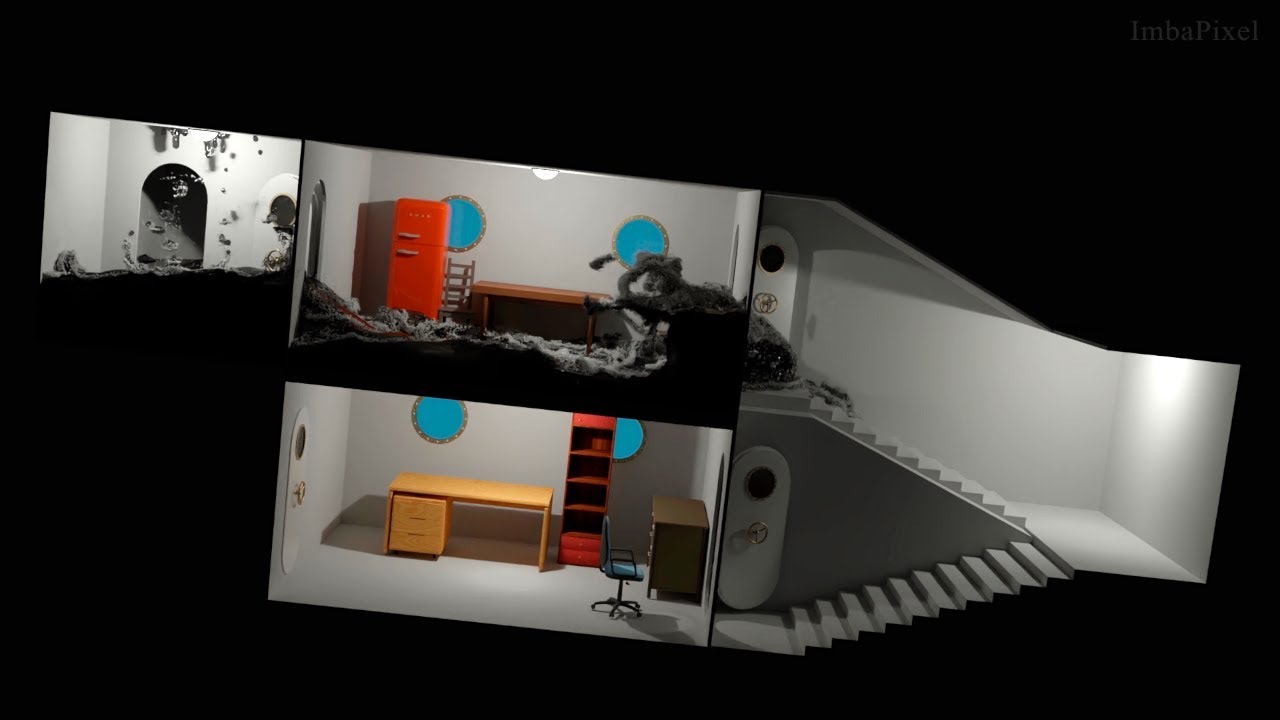

Scientists and maritime historians use complex computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to figure out exactly how 46,000 tons of steel reacted when it met an iceberg. It wasn't just a simple "hit and sink" scenario. It was a mechanical failure of epic proportions. When you look at a digital simulation of the titanic sinking today, you aren't just looking at a video; you're looking at millions of data points representing water pressure, structural stress, and buoyancy shifts.

The Physics of the Breakup

For decades, people argued about whether the ship actually broke in two. Some survivors said it did. Others swore it went down in one piece. It wasn't until Robert Ballard found the wreck in 1985 that we knew for sure: the ship was in pieces. But how?

Early simulations suggested the ship reached a high angle, maybe 45 degrees, before snapping. Modern versions say no. It probably broke at a much shallower angle, maybe only 11 to 15 degrees. Why does this matter? Because it changes everything we know about the structural integrity of Olympic-class liners. When the bow filled with water, it pulled the stern up. Steel has a limit. Eventually, the "keel," which is basically the ship's backbone, couldn't take the tension. It buckled.

Think about it like a giant lever.

The water in the bow was the weight. The air in the stern was the float. The middle was the pivot point. A simulation of the titanic sinking created by researchers like Parks Stephenson or teams at companies like RMS Titanic Inc. shows that the ship basically tore itself apart from the top down. The double bottom—the strongest part of the ship—was the last thing to go. It acted like a hinge for a few seconds before the two halves finally separated.

The Titanic Honor and Glory Project

If you want to see the most accurate simulation of the titanic sinking currently available, you have to look at the "Titanic: Honor and Glory" team. These guys are obsessive. They aren't just animators; they are historians using Unreal Engine 5 to recreate the event in real-time. Their 2-hour and 40-minute simulation is haunting. You see the lights flicker. You see the specific lifeboats being lowered.

Most importantly, you see the water.

Water doesn't just "fill" a ship. It surges. It traps air. It creates "pockets" that eventually explode under pressure. In their simulations, you can see how the water moved through the E-Deck "Scotland Road" corridor. This was a long hallway that ran almost the length of the ship. It acted like a highway for the flooding, allowing water to bypass some of the watertight bulkheads that were supposed to keep the ship afloat.

🔗 Read more: Current Events Artificial Intelligence: Why the "Agent Era" Is Finally Here

Why 1912 Engineering Failed

People love to blame the "brittle steel" or the "missing rivets." While there’s some truth to the rivet theory—specifically that the iron rivets in the bow were weaker than the steel ones in the center—the real culprit was the design of the bulkheads.

The Titanic was "unsinkable" because it could stay afloat with any two of its sixteen compartments flooded. It could even handle the first four compartments being open to the sea. But the iceberg sliced a 300-foot gash that affected the first five.

This is where the "ice cube tray" analogy comes in.

The bulkheads didn't go all the way to the top. Once one compartment filled, the ship tilted, and the water spilled over the top of the wall into the next one. A digital simulation of the titanic sinking shows this "spillover effect" perfectly. It was a slow-motion disaster. For the first hour, the ship hardly looked like it was sinking at all. Then, the center of gravity shifted past the point of no return.

Honestly, the math is terrifying.

💡 You might also like: Two Way Switch Two Lights: How to Actually Wire It Without Losing Your Mind

The Final Plunge

Once the bridge dipped underwater, the end came fast. This is the part of the simulation of the titanic sinking that most people find the most disturbing. As the stern rose, the pressure on the internal structures became insane. We’re talking about thousands of pounds per square inch.

When the ship broke, the bow section was already full of water. It drifted down relatively smoothly, like a falling leaf. It hit the bottom at about 30 miles per hour, which is why the bow still looks like a ship today.

The stern? That was a different story.

The stern was still full of air when it broke off. As it sank, the air stayed trapped inside until the outside water pressure became too much. Basically, the stern imploded. It didn't just sink; it disintegrated as it fell two miles to the ocean floor. That’s why the stern wreck is a mangled mess of twisted steel that barely looks like a boat. Simulations help us reconstruct that chaotic descent, showing how pieces of the ship were ripped off by the sheer force of the water rushing past at high speeds.

Modern Simulations vs. Reality

You've probably seen those viral TikToks or YouTube shorts showing a "1-minute" simulation of the titanic sinking. Most of those are garbage. They ignore the physics of "free surface effect," which is what happens when a large volume of water moves around inside a moving vessel.

Real scientific simulations, like those used by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), focus on the metal. They look at the "Charpy V-notch" impact tests of the steel recovered from the wreck. They found that the steel became "brittle" in the 28-degree water. It didn't bend; it snapped.

- Real-time duration: 2 hours, 40 minutes.

- Water temperature: 28°F (-2°C).

- Depth of wreck: 12,500 feet.

- Breakup altitude: Roughly 11-15 degree tilt.

It’s easy to look at a 3D model and feel detached. But when you see a simulation that includes the exact time the Grand Staircase dome collapsed or when the lights finally failed (roughly 2:18 AM), it becomes a lot more human. The lights stayed on almost until the very end because the engineers stayed below, keeping the generators running. They died so that others could see to get into the lifeboats.

Improving Your Own Research

If you are looking to explore a simulation of the titanic sinking for educational or historical purposes, don't just settle for a movie clip. Most movies prioritize drama over physics.

Start by looking at the 2012 James Cameron-led "final word" simulation. He brought together a team of naval architects and forensic artists to reconcile the 1997 film with the actual wreck evidence. They corrected the "breakup" sequence significantly. Instead of the stern standing vertical for minutes, they showed it falling back, then being pulled under by the sinking bow.

💡 You might also like: Setting Up a Blink Doorbell Without Losing Your Mind

Also, check out the "Titanic VR" experience or "Titanic: Honor and Glory." These allow you to walk through the ship as it floods. It’s a bizarre feeling. You get a sense of the scale that a flat screen just can't give you. You realize that a "watertight door" isn't just a door; it’s a massive slab of iron that stood between life and death.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts:

- Compare the Sources: Watch the 1958 film A Night to Remember and compare its sinking sequence with a modern CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) simulation. You’ll notice the 1958 version doesn't show the ship breaking—that’s because, at the time, the official consensus was that it sank intact.

- Study the Deck Plans: To understand a simulation of the titanic sinking, you need to know the layout. Find a high-resolution map of the E-Deck and F-Deck. Notice how few stairs led from the bottom of the ship to the top.

- Analyze the Metallurgy: Read the NIST reports on the Titanic's steel. Understanding "ductile-to-brittle transition" will make every simulation you watch much more meaningful. You’ll see the hull plates popping off not just because of the iceberg, but because the steel was literally too cold to flex.

- Follow the Wreckage Path: Look at debris field maps. The way the "big pieces" are scattered tells the story of the breakup. The engines, which are five stories tall, fell straight down, while lighter pieces like coal and china drifted further away.

The Titanic isn't just a ghost story. It’s a data set. Every time we run a new simulation of the titanic sinking, we learn something about fluid dynamics, metallurgy, and human error. It’s a tragedy that we've turned into a science, and that’s probably the best way to keep the memory of the passengers alive—by finally getting the facts right.