You’re sitting in front of your computer, headphones on, listening to a series of high-pitched rhythmic beeps that sound like a frantic bird trapped in a tin can. To the uninitiated, it’s just noise. But to a ham radio enthusiast or a history buff, it’s a message. You want to know what it says, but your brain isn't exactly wired to process 20 words per minute on the fly. This is exactly where a morse code translator from audio becomes your best friend, though most people underestimate how finicky these tools can be.

Decoding a digital text file is easy. Decoding live, noisy, or recorded audio is a completely different beast.

The messy reality of audio decoding

Honestly, if you go into this thinking you can just hold your phone up to a scratchy speaker and get a perfect Shakespearean sonnet, you're going to be disappointed. Background noise is the absolute killer of accuracy. A door slamming in the background or even the hum of an air conditioner can register as a "dot" or a "dash" to a sensitive algorithm.

Most software uses something called Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to visualize the audio frequency. Basically, it looks for the specific pitch of the beeps—usually somewhere between 400Hz and 800Hz—and tries to separate that from the static. If the signal is "clean," it's a breeze. If it’s coming off a Shortwave radio with fading (QSB) and atmospheric crackle, even the most expensive morse code translator from audio will start spitting out gibberish like "E E T T 5 R."

It’s frustrating. It really is.

But when it works? It feels like magic. You’re suddenly tapping into a tradition that dates back to the 1830s, using 21st-century processing power to bridge the gap.

How these translators actually "think"

Software like fldigi or the various web-based CW (Continuous Wave) decoders don't just "hear" the letters. They measure timing. Morse code is built on a ratio system. A dash is three times as long as a dot. The space between parts of a letter is the length of one dot. The space between words is seven dots.

🔗 Read more: Apple Create Apple ID: Why You’re Probably Doing It Wrong and How to Fix It

The problem is humans.

When a person taps out Morse code—especially using a straight key rather than an electronic iambic keyer—they have a "fist." This is a fancy way of saying they have a personal rhythm that isn't mathematically perfect. They might linger on the final dash of a word or cut their spaces too short. A high-quality morse code translator from audio has to use adaptive algorithms to "learn" the sender's speed and quirks in real-time.

If the software doesn't adapt, the text quickly turns into a string of "E"s and "I"s because it can't tell where one character ends and the next begins.

The role of frequency filters

If you're using a tool like the Morse Decoder app or a browser-based solution, look for a "waterfall" display. This is a visual representation of the audio spectrum. You’ll see a bright line where the Morse signal is loudest. By narrowing the filter—basically telling the computer to ignore everything except that one tiny sliver of sound—you massively increase your chances of a successful decode.

It's sort of like trying to hear a friend whisper in a crowded bar. You have to tune everything else out.

Real-world tools that actually work

There are dozens of options out there, but they aren't created equal.

- Fldigi: This is the gold standard for amateur radio operators. It’s open-source and incredibly powerful. It handles noise better than almost anything else because it allows for granular control over the audio filters. It looks like it was designed for Windows 95, but don't let the clunky interface fool you.

- MRP40: Many enthusiasts swear by this one for weak signals. It’s a paid software, but its ability to pull a signal out of the "mud" is legendary in the CW community.

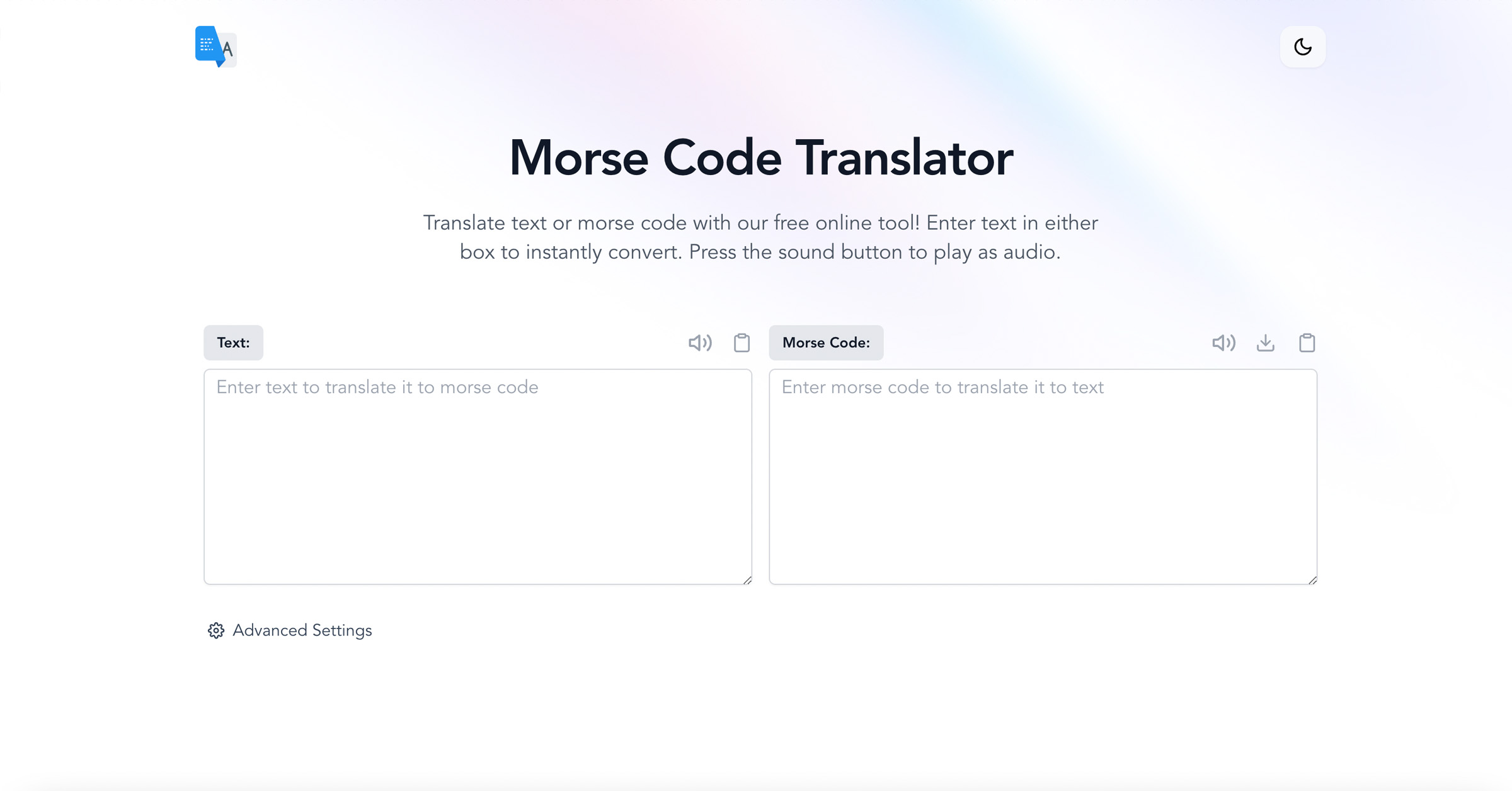

- Web-based Decoders: Sites like Morsecode.world offer audio uploading features. These are great for clean recordings or YouTube videos, but they usually struggle with live radio input compared to dedicated desktop software.

- Mobile Apps: "Morse Decoder" on iOS and Android is surprisingly decent for casual use. It's great for when you're watching a movie and want to know if the "SOS" in the background is actually an Easter egg or just random beeping.

Why we still care about Morse in 2026

You might wonder why we’re even talking about this. Isn't Morse code dead?

Not even close.

In the amateur radio world, CW remains one of the most efficient ways to communicate over vast distances. Because the signal is so narrow, it can punch through when voice signals (SSB) are completely drowned out by solar flares or interference. It’s the "low-bandwidth" king.

Then there’s the "cool factor." From escape rooms to ARG (Alternate Reality Games), developers love hiding messages in audio. Knowing how to use a morse code translator from audio effectively makes you the smartest person in the room when those puzzles pop up.

Common pitfalls to avoid

Don't crank the volume. It's the most common mistake. If the audio is too loud, it "clips," squaring off the waveforms and making it impossible for the software to distinguish the start and end of a beep. Keep the input levels in the yellow zone—never the red.

Another big one: sampling rates. If you're recording audio to decode later, use at least a 44.1 kHz sample rate. Anything lower might jitter the timing of the dots, which leads to—you guessed it—more gibberish.

💡 You might also like: How to Turn Off Are You Still Watching YouTube: The Real Fix for Autoplay Interruptions

Better results through hardware

If you’re serious about this, stop using the built-in microphone on your laptop. It picks up the fan noise and the sound of your own breathing. Use a direct line-in (an aux cable) from your radio or audio source to your computer’s sound card. If you're using a smartphone, a cheap TRRS interface can bridge the gap.

By eliminating the "air" between the speaker and the mic, you're giving the morse code translator from audio a pristine signal to work with. The difference in accuracy is night and day. Honestly, it’s the single biggest upgrade you can make.

Navigating the learning curve

It’s worth noting that software is a supplement, not a replacement. Most experienced operators use their ears and the software simultaneously. The human brain is actually incredible at filtering out noise—sometimes better than a basic algorithm. You’ll find that as you use these tools, you start "hearing" the letters yourself. You'll recognize the "di-dah" of an 'A' before the text even appears on the screen.

There is a certain meditative quality to it. Watching the text scroll across the screen, decoded from nothing but rhythmic pulses of electricity or sound, is deeply satisfying.

Actionable steps for your first decode

To get the best results right now, follow this specific workflow.

First, find a clean source. If you don't have a radio, go to a WebSDR (Software Defined Radio) site and tune to the 40-meter band (around 7.000 to 7.030 MHz). You'll almost always hear Morse code there.

Next, route that audio into your chosen morse code translator from audio. If you're on a PC, you can use "VB-Audio Virtual Cable" to send the audio from your browser directly into fldigi without using a physical cable.

Once the signal is flowing:

📖 Related: How Much Does New iPhone Cost: What Most People Get Wrong

- Center the signal in your software's waterfall display.

- Adjust the "squelch" or threshold so the software only triggers when a beep happens.

- Watch the WPM (Words Per Minute) counter. If it’s jumping wildly between 10 and 40, your signal is too noisy or your filters are too wide.

- Narrow your bandpass filter until the "ghosting" disappears.

Don't get discouraged if the first few lines are nonsense. Morse code is a language of nuances. Sometimes the sender just has a "sloppy" style, and no amount of software tuning will fix that. In those cases, you just have to look for patterns in the gibberish and try to piece it together like a crossword puzzle. It’s part of the fun.

If you're using this for a specific project or just a hobby, the key is consistency. The more you "see" the audio as it's decoded, the better you'll understand the underlying structure of the code itself. Eventually, you might not even need the translator anymore.

Pro Tip: If you're struggling with a particularly difficult audio file, try slowing it down by 25% in a program like Audacity before running it through the decoder. Just make sure the software's WPM setting isn't "locked," or it will get very confused by the slower tempo. This trick works wonders for old, degraded recordings from historical archives.