You’ve probably stepped on a few today without even thinking. Most of us see ants as these tiny, mindless black specks that ruin a picnic or invade the sugar jar. But honestly? Put ants under a microscope and you aren’t looking at a pest anymore. You’re looking at a high-tech armored vehicle equipped with sensory tech that makes a Silicon Valley startup look primitive. It’s kinda terrifying once you see the hair.

Seriously, the hair.

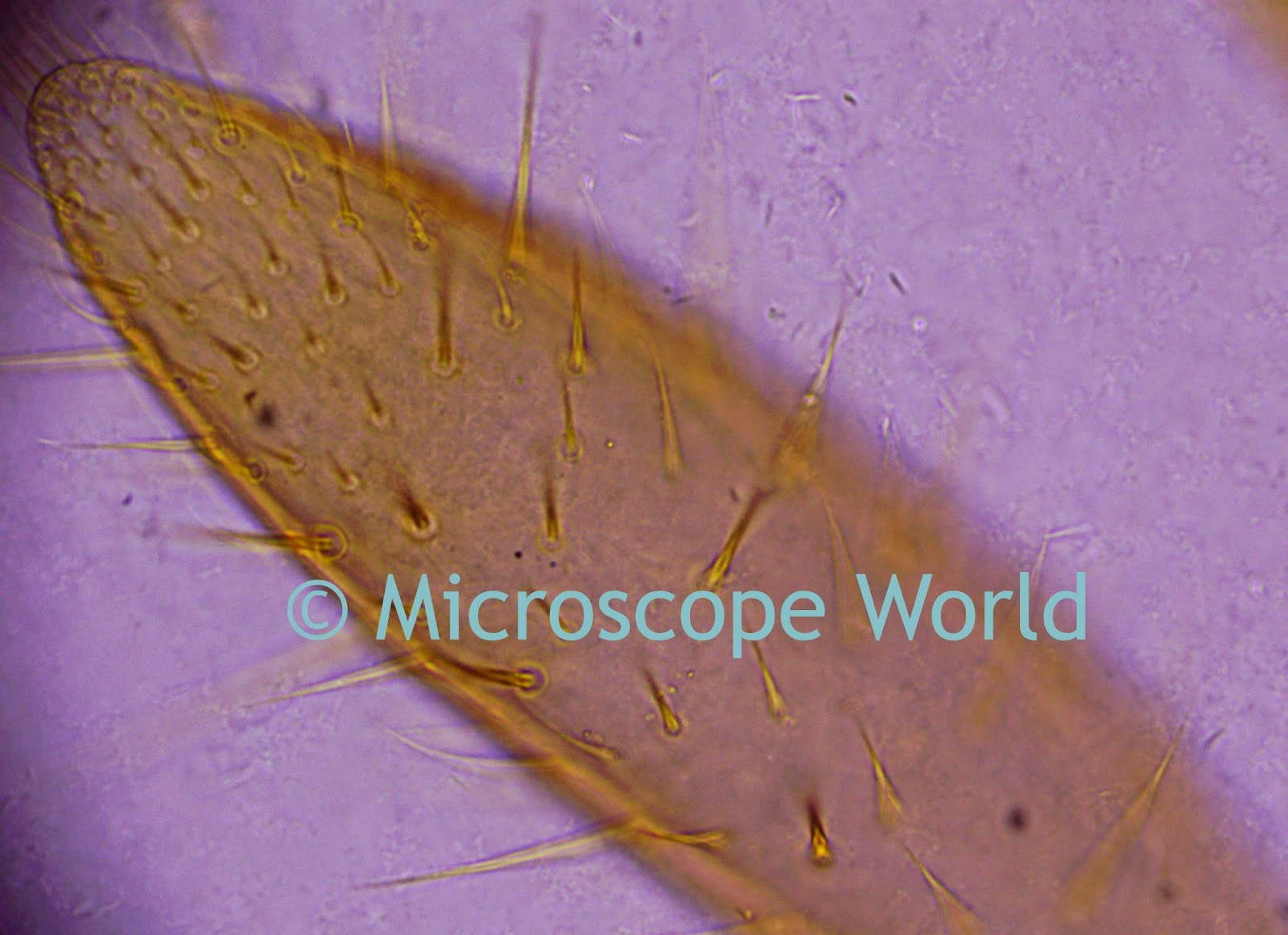

Most people assume ants are smooth like plastic toys. They aren't. When you zoom in using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), you see these stiff, bristly structures called setae. They’re everywhere. They poke out from the joints, the mandibles, and even the eyes. These aren't just for show; they’re biological sensors that detect vibrations and air currents. If you’ve ever wondered how an ant knows you’re about to squish it before your finger even gets close, that’s why.

👉 See also: App Store Optimization Keywords: Why Most Developers Still Fail at the Basics

The Face Only a Myrmecologist Could Love

When you first get a look at the head of ants under a microscope, the eyes are usually what grab you. Or rather, the lack of "real" eyes. Ants have compound eyes made of many tiny lenses called ommatidia. Depending on the species, like the Gigantiops destructor, these eyes can be massive and wrap around the head. But in others, they’re almost nonexistent.

The mandibles are the real stars of the show, though.

Look at a Trap-jaw ant (Odontomachus) under a high-powered lens. Those jaws aren't just teeth; they’re spring-loaded biological traps. They can snap shut at speeds of 145 miles per hour. That’s faster than a blink. Under the microscope, you can see the serrated edges that look more like a steak knife than a bug part. Scientists like Dr. Magdalena Sorger have spent years documenting these structures, showing how some ants use these jaws to catapult themselves backward out of danger. It’s a literal ejector seat built into their face.

Then there are the antennae. They look like weird, segmented clubs. But zoom in closer. You’ll see thousands of tiny pores. These are chemoreceptors. Ants don't "smell" the way we do; they decode a chemical map of the world. They’re basically "reading" the sidewalk. When an ant taps its antennae on the ground, it’s downloading data left by its sisters.

Armor and Architecture

The exoskeleton isn't just a shell. It’s a complex layering of chitin. If you’ve ever seen a metallic green ant or a shimmering golden carpenter ant, the microscope reveals why they sparkle. It’s not pigment. It’s structural color. Tiny microscopic ridges on the shell manipulate light waves, reflecting specific colors back at you. This is the same tech used in high-end security holograms on credit cards.

It’s crazy to think about.

A tiny creature in your driveway is walking around with physics-based cloaking and armor plating. If you look at the joints—the places where the legs meet the thorax—you see a marvel of engineering. There’s a specific "neck" joint in the common field ant that can support 5,000 times the ant's own body weight. For a human, that would be like standing still while holding a Boeing 747 on your head.

Research from Ohio State University used micro-CT scans to look inside these joints. They found that the soft tissue and hard exoskeleton interface in a way that distributes stress perfectly. We still can't replicate that in robotics without it being bulky and awkward. Ants do it while carrying a dead moth up a vertical wall.

🔗 Read more: Why Is Everything Down Right Now: The Real Reason Your Apps Keep Breaking

Why Do They Look So... Angry?

People often say ants under a microscope look like monsters or aliens. There’s a famous photo by Eugenijus Kavaliauskas that went viral a couple of years ago. It showed a close-up of a Carpenter ant’s face. People freaked out because it looked like a red-eyed demon from a horror movie.

But here’s the thing: those "red eyes" weren't actually eyes.

They were the bases of the antennae. The actual eyes were further back and out of focus. This is a classic example of how our brains try to find human faces in things that aren't human. This is called pareidolia. In reality, the ant isn't angry. It doesn't have the brain hardware for "anger" as we know it. It just has a very rigid, functional face designed for digging, biting, and carrying.

The Weird World of Ant "Fur"

We need to talk about the Saharan Silver Ant (Cataglyphis bombycina). If you put this specific type of ants under a microscope, you’ll see something beautiful. Their bodies are covered in triangular-shaped hairs.

Why triangular?

- They reflect visible and near-infrared light.

- They help the ant radiate heat back into the atmosphere.

- They create a silvery sheen that protects them from the 150-degree desert sun.

Most insects would cook instantly in the Sahara. These ants have a literal space suit. When you see those hairs under a microscope, they don't look like hair anymore. They look like prisms. It’s a level of evolutionary detail that you just can't appreciate from six feet above the ground.

The Logistics of Micro-Photography

Capturing these images isn't as simple as pointing a phone at a bug. To get those crystal-clear shots where every hair is visible, photographers use a technique called focus stacking.

🔗 Read more: Why Pictures From Surface of Mars Still Look So Weird to Us

Because the depth of field is so shallow at high magnifications, only a tiny sliver of the ant is in focus at once. A photographer might take 50, 100, or even 500 individual photos, moving the camera a fraction of a millimeter each time. Then, they use software to stitch only the sharp parts together.

It takes hours.

Sometimes days.

And then there's the prep. To use an SEM, the ant usually has to be coated in a thin layer of gold or platinum so the electrons can bounce off it correctly. You’re literally looking at a gold-plated ant. This is why many professional scientific images look like statues; in a way, they are.

What Most People Get Wrong

A big misconception is that all ants look the same under the lens. They don't. A leafcutter ant has these massive, rugged "shoulders" (the pronotum) with spikes to deter predators. A velvet ant—which is actually a wingless wasp, but let’s count it for the aesthetic—has thick, plush-looking hair that’s actually a defense mechanism against stings.

The diversity is staggering.

There are over 12,000 species of ants. Each one has adapted its "micro-gear" for its specific environment. Some have hooked feet for walking on smooth leaves. Others have flat, shovel-like heads for blocking the entrance to their nest. When you start looking at ants under a microscope, you realize there is no such thing as "just an ant."

Practical Steps for Seeing Them Yourself

You don't need a million-dollar lab to start seeing this stuff. It’s actually pretty accessible now.

- Buy a USB Digital Microscope: You can get these for under $50. They won't give you SEM-level detail, but you’ll see the hairs and the compound eyes clearly.

- Macro Lens for Your Phone: These clip-on lenses are surprisingly good. They’re great for "field work" in your garden.

- Find a Dead Specimen: Don't try to photograph a live ant under a lens; they move way too fast. Look on windowsills or near porch lights.

- Lighting is Everything: Use a bright, diffused LED. If the light is too direct, the exoskeleton will reflect too much glare, and you’ll lose all the detail.

- Steady the Base: Even the vibration of a passing truck can blur a micro-photo. Use a stable table.

Getting a look at ants under a microscope is a humbling experience. It’s a reminder that there’s a whole world of complex engineering happening right under our feet, completely ignored by us. These creatures are the primary movers of soil on Earth. They’re the "glue" of most ecosystems. Seeing the serrated edge of a mandible or the prismatic hair of a desert dweller makes it a lot harder to just see them as pests. They’re masterpieces of biological design, refined over 140 million years. Next time you see one on the sidewalk, maybe give it a little more credit. It’s wearing armor we can barely understand.