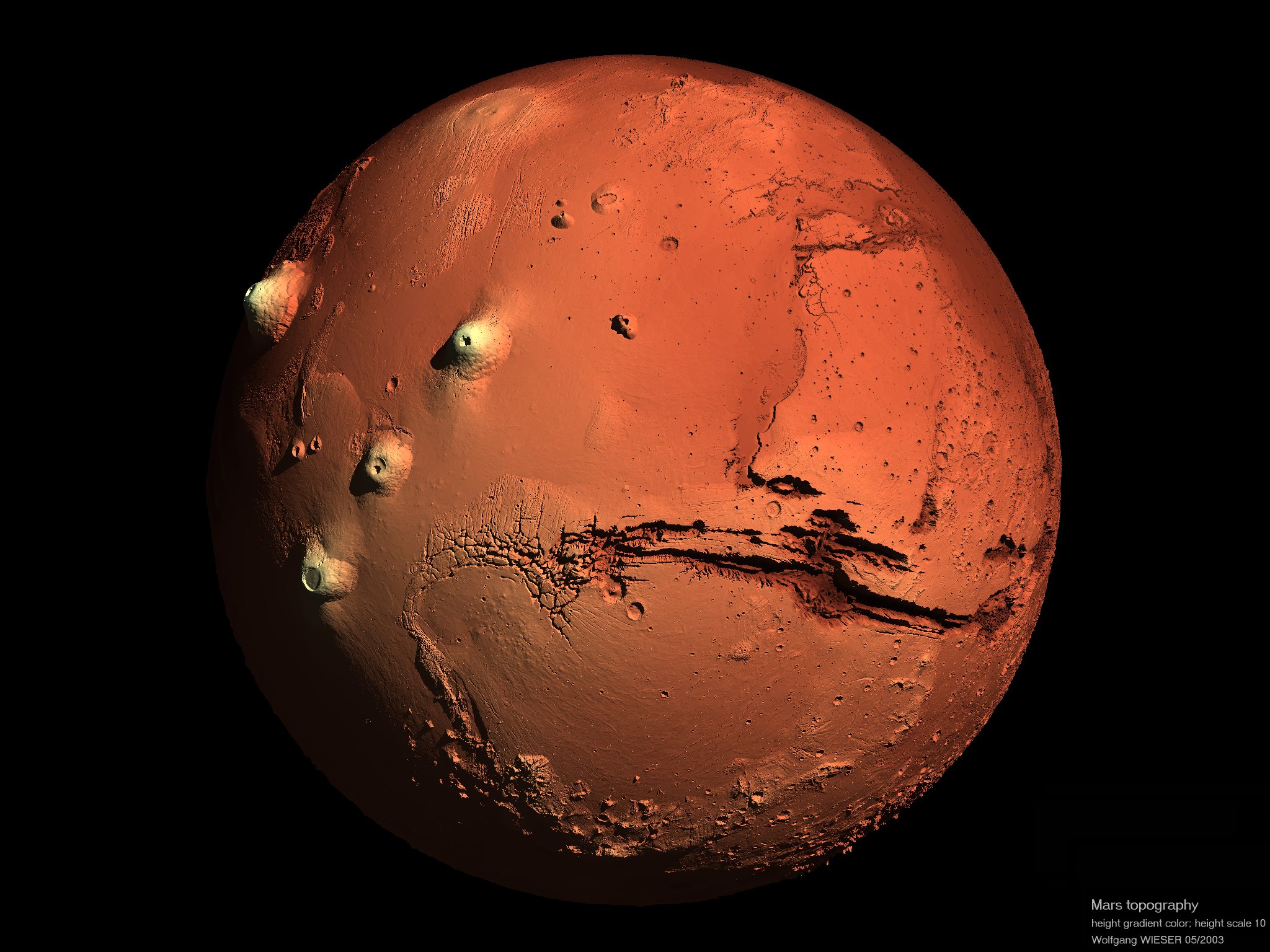

You’ve seen them. Those sweeping, burnt-orange vistas that look like a Southwest desert on steroids. Or maybe you've seen the weird ones—the high-contrast, blue-tinted crags that look like they belong in a 1970s sci-fi flick. Honestly, if you’re looking at pictures of the mars, you’re probably wondering why the planet seems to change its personality every time a new rover lands. Is it red? Is it butterscotch? Is it grey?

The truth is a bit messy.

NASA doesn’t just "take a photo" like you do with an iPhone. When the Perseverance rover or the older Curiosity beast snaps a frame, they aren't using a standard CMOS sensor meant for Instagram. They’re capturing raw data. This data is filtered, stretched, and color-corrected to help scientists see the difference between a boring rock and a scientifically "spicy" mineral. If you want to understand what you're actually looking at, you have to peel back the layers of how we visualize the fourth rock from the sun.

The Raw Reality vs. What We See

Most of the early pictures of the mars we got from the Viking landers back in the 70s were a bit of a guess. Engineers literally adjusted the color knobs on the monitors until the sky looked "right"—but their version of right was based on Earth's blue sky. They quickly realized that the Martian atmosphere, choked with fine magnetite and limonite dust, actually scatters light in a way that turns the sky a pinkish-salmon color during the day.

It’s dusty.

That dust is everywhere. It’s why the planet looks like a rust bucket from a distance. Chemically, we’re talking about iron oxide. Rust. But the "true color" of Mars is a point of massive debate among planetary scientists. Jim Bell, who has worked extensively on the Pancam and Mastcam-Z systems, often talks about how "true color" is a bit of a unicorn. Human eyes have never been there. We can only approximate what a human standing in Jezero Crater would see through a dusty visor.

Why Some Pictures of the Mars Look Blue

You’ve probably stumbled across a photo that looks like a neon nightmare. These are "false color" images. They aren't "fake," but they are manipulated for a very specific reason: geological clarity.

Imagine you’re looking at a pile of grey rocks. To your eyes, they all look the same. But if you use an infrared filter, one rock might glow like a lightbulb because it contains carbonates or sulfates. By assigning "fake" colors—like making infrared look bright red and ultraviolet look deep blue—scientists can spot the history of water on the planet from a single glance.

Then there’s the blue sunset. This is one of the coolest things about Martian photography. On Earth, our thick atmosphere scatters blue light, leaving the reds and oranges for sunset. On Mars, the dust particles are just the right size to allow blue light to penetrate the atmosphere more efficiently near the sun. So, while the day is a hazy butterscotch, the sunset is a ghostly, pale blue.

The Gear Behind the Lens

The hardware is wild. We aren't just talking about one camera. Perseverance, the current heavy hitter on the surface, has 23 cameras.

- Mastcam-Z: This is the "eyes" of the rover. It can zoom, it can take 3D stereoscopic images, and it can shoot video.

- WATSON: No, not the AI. This stands for Wide Angle Topographic Sensor for Operations and eNgineering. It’s located on the arm and gets those close-up, microscopic textures of rocks.

- SuperCam: This one literally shoots lasers at rocks to vaporize them and then takes a picture of the glowing plasma to see what it's made of.

When you look at pictures of the mars taken by these instruments, you’re looking at millions of dollars of radiation-hardened glass and sensors designed to survive -100 degree nights.

The "Face" and Other Optical Illusions

We can't talk about Mars photos without mentioning pareidolia. That’s the fancy psychological term for seeing faces in clouds or burnt toast. The "Face on Mars" from the Viking 1 orbiter in 1976 is the gold standard of this. In low-res, grainy black and white, a mesa in the Cydonia region looked exactly like a humanoid face.

People lost their minds.

Tabloids claimed it was proof of an ancient civilization. Years later, Mars Global Surveyor flew over the same spot with much better cameras and… it’s just a lumpy hill. Shadows are everything. Recently, people thought they saw a "doorway" in a Curiosity photo. It was actually just a shear fracture in a rock face, about 12 inches tall.

Processing the Data: From Deep Space to Your Screen

The journey of a photo is a long one.

First, the rover beams the data up to an orbiter like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) passing overhead. The MRO then acts as a relay, screaming that data across the vacuum of space to the Deep Space Network antennas in California, Spain, or Australia.

The raw files are "black and white" (grayscale) data sets. These are called "data products." To get a color image, the rover takes three separate photos through red, green, and blue filters. Back on Earth, software stitches these together. If the rover moved slightly, or if the wind blew dust during the three-shot sequence, you get "ghosting" or weird artifacts.

What the Future Holds for Martian Imagery

We are moving past static photos. The Ingenuity helicopter gave us the first aerial pictures of the mars from a powered aircraft. That changed the game. Suddenly, we had a "scout's eye view" of the terrain that orbiters couldn't see and rovers couldn't reach.

Now, the focus is on the Mars Sample Return mission. For the first time, we won't just have pictures; we will have the actual rocks that the pictures were taken of. Comparing the high-res digital images with the physical sample under an Earth-based microscope will be the ultimate calibration.

How to Explore Mars Photos Yourself

You don't have to wait for a news outlet to post a "Top 10" list. NASA is surprisingly transparent. They have "Raw Image" galleries for Curiosity and Perseverance that update almost daily.

- Check the timestamp: Look at the "Sol" (Martian day) count. You can see what the rover saw just 24 hours ago.

- Look for the calibration target: Most rovers have a small "color palette" or a sundial (MarsDial) mounted on them. This helps engineers calibrate the color of the photos by comparing them to known colors on the rover.

- Scan the horizon: Look for "dust devils." These are small whirlwinds that often show up as faint, ghostly streaks in long-exposure shots.

Practical Steps for High-Res Discovery

If you really want to dive into the best pictures of the mars without the fluff of social media, head straight to the source. The Planetary Data System (PDS) is the archive used by real scientists. It’s a bit clunky, but it’s where the high-bit-depth TIFF files live.

💡 You might also like: Map Longitude Latitude United States: What Most People Get Wrong

For a more user-friendly experience, follow the "Raw Images" feed on the NASA Mars Exploration Program website. You can filter by camera type—if you want landscapes, look at the Navigation Cameras (Navcams); if you want mineral textures, look at the Sherloc/Watson images.

Don't just look for the pretty ones. The "ugly" photos—the ones with lens flares, blurry edges, or weird shadows—often tell the most interesting stories about the harsh environment the rovers are battling every single day. Look for the "Mars Hand Lens Imager" (MAHLI) shots to see the actual grains of sand that were moved by Martian winds billions of years ago. It’s the closest any of us will get to standing there until the 2030s or 2040s.

Keep an eye on the "Hazcam" (Hazard Avoidance Camera) shots too. They are usually wide-angle and mounted low to the ground. They give you a "bug's eye view" of the Martian soil that makes the planet feel incredibly intimate and real, rather than just a speck in a telescope.

Explore the official NASA JPL raw image archives for the Perseverance rover. Use the "Sol" filter to find images from the most recent Martian days. Download the "Full Res" versions rather than the thumbnails to see the intricate layering in the rocks of the delta deposits. This is where the clearest evidence of ancient water resides. Focus on the Mastcam-Z images for the most color-accurate representations of the landscape as it would appear to the human eye.