You’re breathing it right now. Oxygen. It’s the invisible engine of life, but if you close your eyes and try to picture it, you probably see a tiny solar system. You see a cluster of red and blue balls in the middle with little electrons orbiting in neat, hula-hoop circles. That's the atom model of oxygen we were all taught in ninth grade. It’s clean. It’s easy to draw. It’s also mostly wrong.

Actually, it’s worse than wrong—it’s a massive oversimplification that hides how weird and chaotic the subatomic world really is. If oxygen actually looked like those textbook diagrams, the universe wouldn't work. Chemistry would break.

What's actually happening inside an oxygen atom?

To understand the atom model of oxygen, you have to stop thinking of electrons as little planets. They aren't. They’re more like a caffeinated swarm of bees that exist in multiple places at once. In a single oxygen atom, you have eight protons and eight neutrons jammed into a nucleus. This core is incredibly dense. If the nucleus were the size of a marble, the whole atom would be the size of a football stadium.

Most of that stadium is empty. Just... nothing. Except for those eight electrons. They don't follow tracks. Instead, they occupy "orbitals," which are basically probability clouds where you’re likely to find them. According to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, we can't actually know exactly where an electron is and how fast it's moving at the same time. We just know where it likes to hang out.

🔗 Read more: Release Date of the Galaxy S7: What Really Happened

The Bohr Model: The beautiful lie

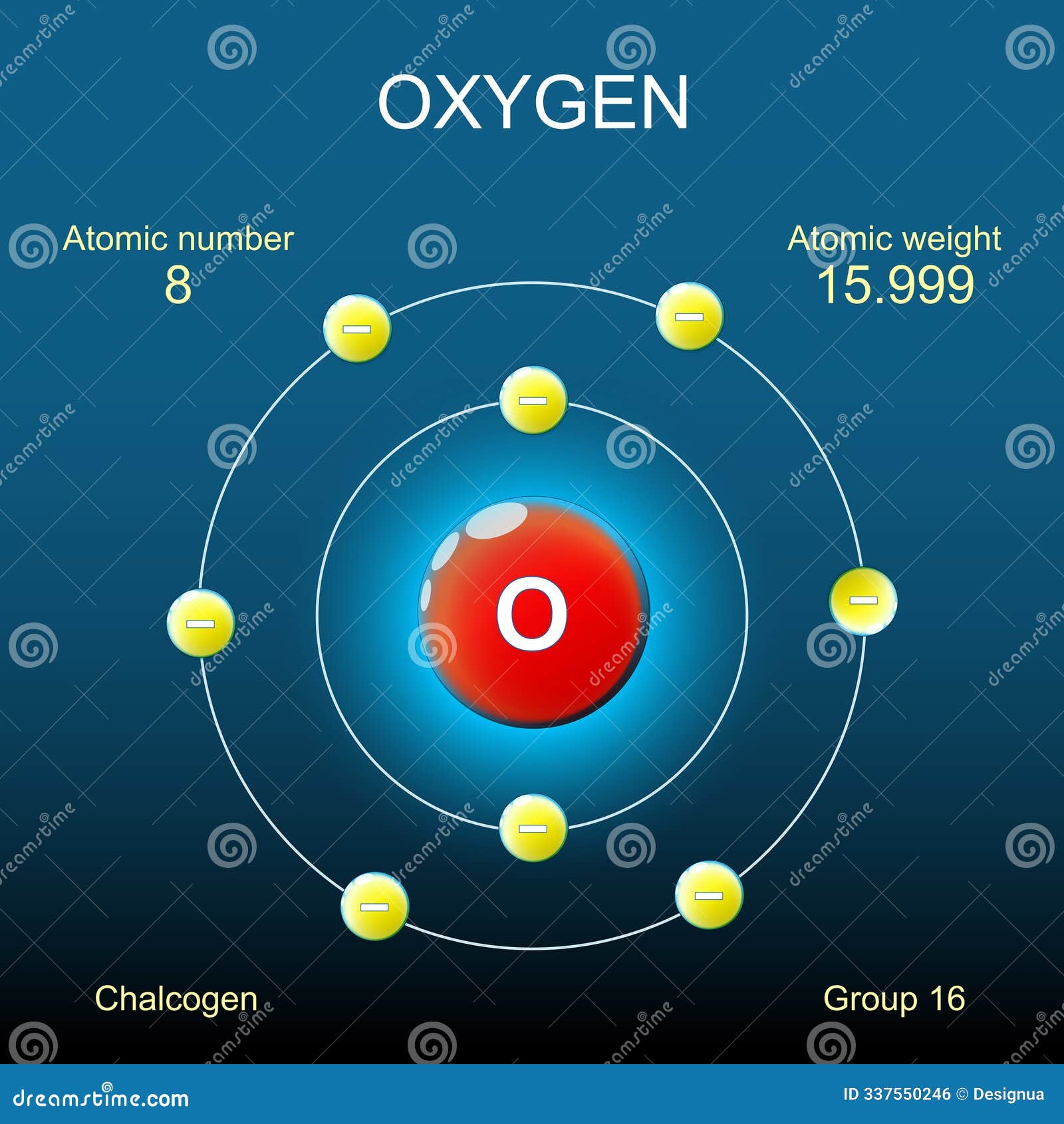

Niels Bohr gave us the classic "solar system" look back in 1913. For oxygen, Bohr’s model shows a nucleus surrounded by two shells. The inner shell holds two electrons. The outer shell holds six.

- The first shell ($K$ shell) is full.

- The second shell ($L$ shell) is "hungry."

Because that outer shell wants eight electrons to be stable—the famous "octet rule"—oxygen is a chemical predator. It is constantly looking to steal or share two more electrons. This is why oxygen is so reactive. It’s the reason iron rusts and why fires burn. It's basically the "bad boy" of the periodic table, always looking to disrupt someone else's stability to fix its own.

Getting technical: The Quantum Mechanical Model

If you want the real atom model of oxygen, you have to look at quantum mechanics. Forget the hula hoops. We’re talking about $1s$, $2s$, and $2p$ orbitals.

- The $1s$ orbital is a sphere right next to the nucleus. Two electrons live here.

- The $2s$ orbital is a larger sphere surrounding the first. Two more electrons here.

- The $2p$ orbitals are shaped like dumbbells. There are three of them, oriented along the $x, y,$ and $z$ axes.

In oxygen, these $p$ orbitals are where the magic happens. Two of the $p$ orbitals have only one electron each. These "unpaired" electrons are the reason oxygen is paramagnetic. Fun fact: if you pour liquid oxygen past a strong magnet, it actually sticks to the poles. A "solar system" model can't explain that. Only the quantum model can.

👉 See also: Why that first earth pic from the moon changed everything we knew

Why the oxygen model matters for your health

Oxygen isn't just a chemistry quiz answer. The way its electrons are arranged—specifically those two lonely, unpaired electrons in the outer shell—dictates how it behaves in your bloodstream.

When oxygen behaves, it helps mitochondria create ATP. When it misbehaves, it becomes a "free radical." Basically, if an oxygen atom gets an extra electron it can't handle or loses one prematurely, it becomes unstable and starts attacking your cells. This is oxidative stress. We take antioxidants (like Vitamin C) specifically to give those aggressive oxygen species the electrons they’re "hunting" for so they stop tearing up our DNA.

Lewis Dot Structures: The "Cheat Code"

For chemists, drawing clouds is hard. So, they use Lewis Dot Structures. For the atom model of oxygen, you just write the letter 'O' and put six dots around it.

- Two pairs of dots.

- Two single dots.

Those two single dots are the "hooks." They represent the spots where oxygen can bond with other atoms. When two hydrogen atoms hook into those spots, you get $H_2O$. Water. The specific angle of those "hooks" is roughly $104.5$ degrees. If the oxygen atom were flat, water wouldn't have the surface tension that allows bugs to walk on it or trees to suck it up from the ground. The 3D shape of the oxygen atom literally makes life on Earth possible.

Misconceptions that just won't die

People think atoms are solid. They aren't. They’re fields of energy. If you removed all the "empty space" from the oxygen atoms in every human being on Earth, the entire human race would fit inside a sugar cube.

Another big one? That electrons "spin" like tops. They don't. "Spin" is just a quantum property—a type of intrinsic angular momentum. It’s not physical rotation. But try explaining that at a dinner party without sounding like a nerd.

🔗 Read more: Doge Clock Live Tracker: Why This Weird Timer Actually Matters for Your Crypto

The future of imaging oxygen

We are getting closer to actually "seeing" these models. Researchers at places like the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory use scanning tunneling microscopy to map electron density. We aren't just guessing anymore; we are seeing the clouds. These images confirm that the quantum atom model of oxygen is the most accurate map we have, even if it's harder to visualize than the old-school circles.

Actionable insights for the curious mind

If you’re trying to master the atom model of oxygen for a class or just for personal knowledge, stop trying to memorize the circles. Do this instead:

- Focus on the 2, 6 split: Remember that 2 electrons are "locked away" inside, and 6 are the "workers" on the outside.

- Visualize the dumbbells: Think of the $p$ orbitals as three balloons tied together at the center. This helps you understand why molecules like water are bent rather than straight.

- Connect it to reactivity: When you see "Oxygen" on a label, think "electron thief." It helps you understand everything from how batteries work to why food goes stale (oxidation).

- Use simulations: Check out the PhET Interactive Simulations from the University of Colorado Boulder. They let you build an oxygen atom from scratch, and it’s way more intuitive than a static image.

The atom model of oxygen is a testament to how far we've come. We went from thinking everything was made of fire and air to mapping the probability clouds of subatomic particles. It’s messy, it’s counterintuitive, and it’s absolutely brilliant.