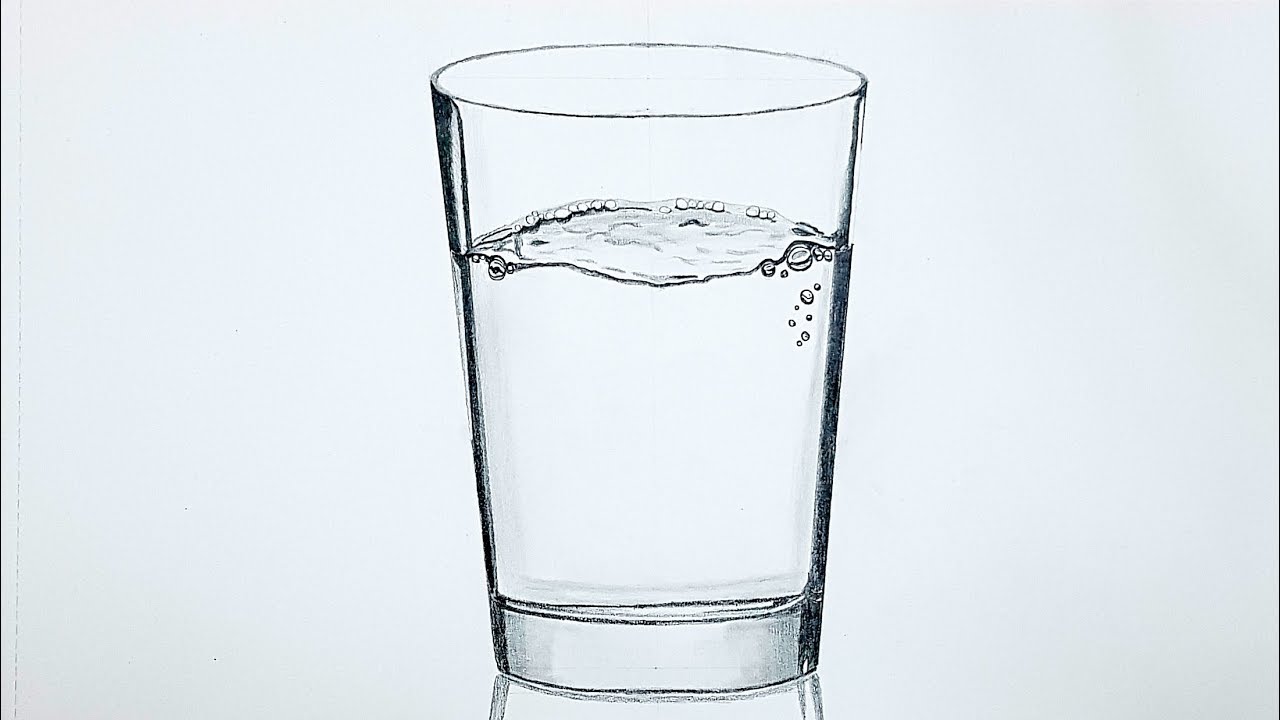

Drawing water is a paradox. It’s clear, yet you can see it. It has no color, but it reflects everything around it. Most beginners sit down and try to draw the "idea" of a glass—two vertical lines and an oval—and then they wonder why it looks like a flat cartoon. If you want to master how to draw a glass of water, you have to stop drawing the object and start drawing the light.

Light is weird. When it hits a transparent surface like glass, it doesn't just stop. It bounces, bends, and shatters into highlights. This is called refraction. Physics matters here. Honestly, if you don't understand that water acts like a lens, your drawing will always look "off."

The Refraction Trap and How to Fix It

The biggest mistake people make is drawing what they think they see rather than what is actually there. Look at a real glass. See that straw or the back edge of the rim? It doesn’t line up. Because water is denser than air, it bends light rays. This is Snell’s Law in action, though you don’t need a calculator to draw it.

You just need eyes.

When you’re learning how to draw a glass of water, you'll notice the part of the glass filled with liquid acts like a magnifying glass. It stretches things. It flips things. If there’s a pattern on the wallpaper behind your glass, that pattern will appear distorted inside the water. Draw that distortion. If you draw the background perfectly straight through the glass, you’ve instantly killed the illusion of realism.

I remember watching a demonstration by the hyper-realistic artist Marcello Barenghi. He doesn't start with "the glass." He starts with the shadows. It sounds counterintuitive. But in a transparent object, the shadows and the highlights are the only things that define the shape.

📖 Related: Aussie Oi Oi Oi: How One Chant Became Australia's Unofficial National Anthem

Mapping the Anatomy of Transparency

Let’s break down what you’re actually looking at. It’s not just a cylinder.

First, there’s the ellipse. That’s the oval shape at the top. Most people draw this too pointy at the ends. It should be a smooth, continuous curve. Then you have the waterline. This is a second ellipse inside the glass. It’s usually a bit thicker and darker than the rim because of the meniscus—the way water "climbs" the sides of the glass slightly.

Then come the highlights. These are your "whites."

- Specular highlights: These are the bright, crisp spots where the light source (like a window or a lamp) reflects directly off the surface.

- Reflected light: This is the softer glow on the shadow side.

- Caustics: This is the cool part. It’s the bright, dancing pattern of light that passes through the water and onto the table.

If you forget the caustics, the glass won't look like it's sitting on the surface. It will look like it's floating in a void.

Why Your Pencil Choice Matters

Don't just grab a yellow No. 2 pencil and hope for the best. You need range.

👉 See also: Ariana Grande Blue Cloud Perfume: What Most People Get Wrong

Use a 4B or 6B for the deepest shadows where the glass meets the table. Use an H or 2H for the faint, ghostly outlines of the glass itself. And for the love of everything, get a high-quality eraser. A precision eraser, like a Tombow Mono Zero, is basically a drawing tool in itself when you're working with glass. You’re not erasing mistakes; you’re "drawing" the light back into the graphite.

The Secret of the Dark Edges

Here is a weird truth about how to draw a glass of water: the edges are often the darkest part.

When you look at the side of a glass, you're looking through the thickest part of the material. This creates a dark "line" that defines the silhouette. But it isn't a solid black line like a coloring book. It’s a gradient. It’s subtle.

Observation over Imagination

Sit a glass of water on your desk right now. Look at the bottom—the "sham" or the heavy base. It’s full of tiny reflections. Little dark bits, little bright bits. It looks like a mess of abstract shapes. If you try to simplify it, you lose the realism. You have to be brave enough to draw those weird, abstract shapes exactly as they appear.

Leonardo da Vinci spent a huge amount of time studying how light moves through water. He noted in his journals that "the surface of every opaque body participates in the color of the object placed before it." This applies to glass tenfold. If you’re wearing a red shirt, there is probably a tiny, distorted speck of red somewhere in that glass of water. Adding that tiny detail makes the viewer's brain go, "Oh, that's real."

✨ Don't miss: Apartment Decorations for Men: Why Your Place Still Looks Like a Dorm

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Symmetry obsession: Perfect symmetry is the enemy of life. While the glass might be manufactured perfectly, the water moves, and the light hits it from one side. One side should always be different from the other.

- Outlining everything: If you draw a hard black line around the whole glass, it will look like a sticker. Real objects are defined by contrast, not outlines.

- Ignoring the surface: The water has a "skin." The top surface of the water reflects the ceiling. It’s not just a hole in the glass.

Mastering the Meniscus and the Bottom

The bottom of the glass is where most people give up. They just draw a flat line. But a glass has thickness. You need to draw the "inside" bottom and the "outside" bottom. The space between those two lines is the thickness of the glass base.

And the meniscus? That tiny curve where the water meets the glass? That’s where the magic happens. It creates a dark band that tells the eye exactly where the liquid ends and the air begins.

Practical Steps for Your Next Sketch

- Set the Stage: Use a single, strong light source. Multiple lights create "flat" images. One lamp from the side is perfect.

- Sketch Lightly: Use a 2H pencil to map out the ellipses. If you press too hard, you’ll dent the paper, and those dents will show up later when you try to shade.

- Find the Black: Find the absolute darkest spot—usually where the glass touches the table—and mark it. This sets your value scale.

- Work the Midtones: Use a blending stump or a tissue to soften the transitions. Glass is smooth, so your shading should be too.

- Lift the Light: Use your eraser to "pop" the highlights at the very end. This is the most satisfying part.

Drawing water isn't about being an "artist" in some mystical sense. It’s about being an observer. It’s about noticing that the "clear" water is actually a collection of greys, blacks, and whites. Once you stop trying to draw "water" and start drawing "shapes of light," you’ve already won.

Get a piece of smooth Bristol paper. It handles blending way better than rough sketchbook paper. Take your time. Glass doesn't rush you, and you shouldn't rush it. The beauty is in the details that most people are too busy to see.