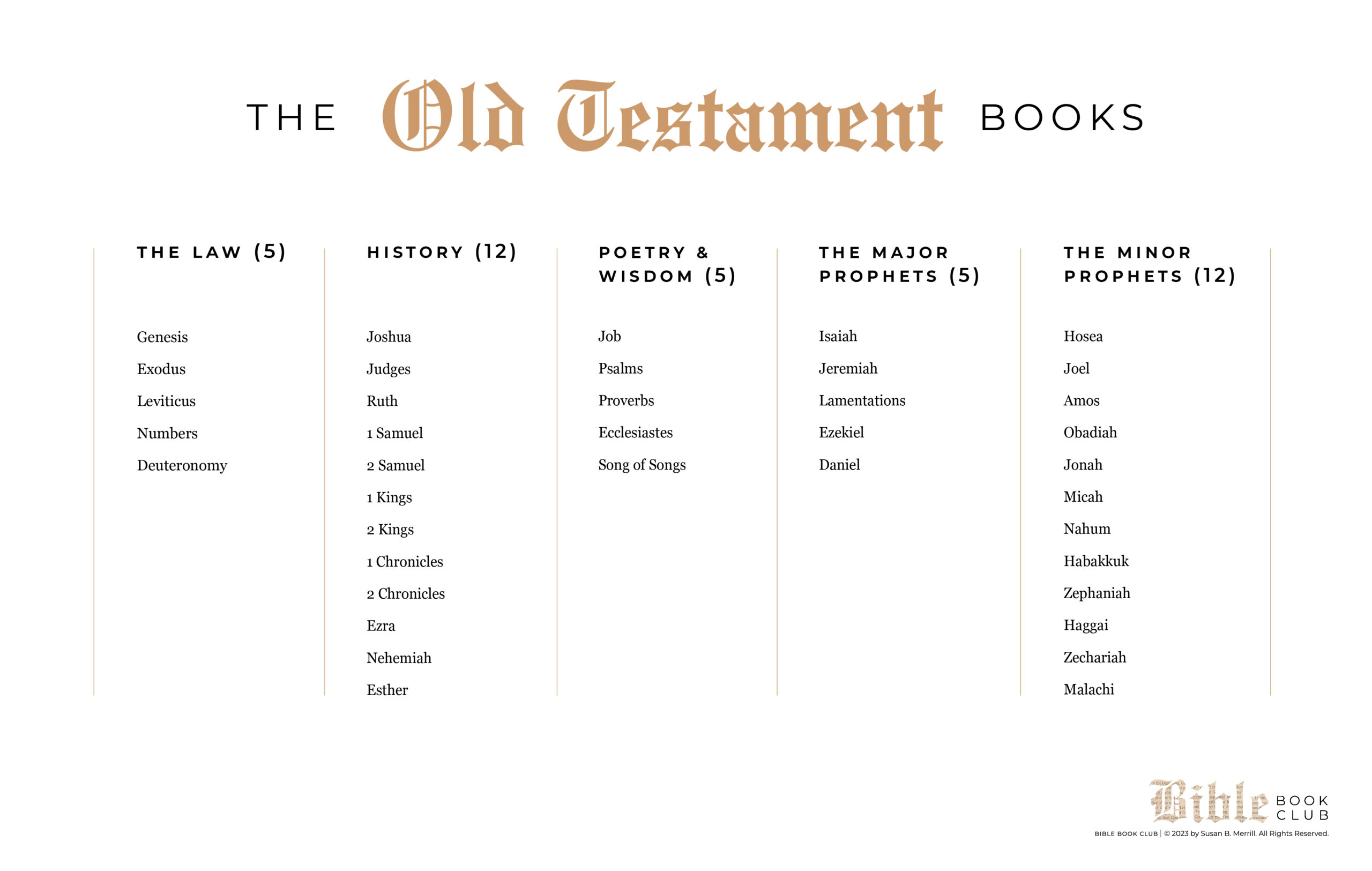

You’ve probably opened a Bible and seen that massive chunk of text at the beginning. It's the Old Testament. Most people think of it as just a long, dusty list of rules and ancient wars, but if you look at the list books of Old Testament creators actually settled on, there is a weird, almost cinematic structure to it. It isn't just a random pile of scrolls. It’s a library.

Honestly, the way we list these books today—starting with Genesis and ending with Malachi—is kind of a historical "remix." If you were a scholar in Jerusalem 2,000 years ago, your list would look totally different. You’d be looking at the Tanakh. The content is mostly the same, but the ending? Completely different vibe.

The Five Books of Moses: The Foundation

Everything starts with the Torah. This is the "Law," but that’s a bit of a boring translation for what it actually is. It's the DNA of the whole thing.

Genesis is the "prequel" to literally everything. You get the cosmos, then a lot of family drama with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It's messy. Then you hit Exodus, which is basically the heartbeat of Jewish identity. Moses, the plagues, the mountain—it’s high-stakes stuff.

Leviticus is where most modern readers give up. Let’s be real. It’s a manual for priests. It’s about blood, grain, and what to do with a moldy house. But for an ancient Israelite, this was the "how-to" for staying connected to the divine. Numbers follows it up with a lot of census data (hence the name) and forty years of wandering around a desert because people couldn't stop complaining. Finally, Deuteronomy is Moses’s long goodbye speech. He’s standing on the edge of the Promised Land, knowing he can’t go in, and he’s basically saying, "Please, don’t mess this up like your parents did."

History and the "Former Prophets"

After the Torah, the list books of Old Testament transitions into what we call the historical books. This is where the action movie starts.

📖 Related: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

Joshua is the conquest. It’s gritty. Judges is worse—it’s a downward spiral of "everyone did what was right in their own eyes," which usually meant total chaos. Then, suddenly, you get Ruth. It’s a tiny, beautiful story about a widow from a foreign land. It feels out of place, right? But it’s there to bridge the gap to the monarchy.

Then comes the heavy hitters:

- 1 & 2 Samuel: The rise of Saul and David.

- 1 & 2 Kings: The golden age of Solomon and the subsequent split of the nation.

- 1 & 2 Chronicles: A retelling of the history, but with a more hopeful, religious spin.

It’s worth noting that in the Hebrew Bible, these aren't always split into "1 and 2." That was a later decision based on how much text could fit on a single physical scroll. Technology literally dictated the table of contents.

Wisdom Literature: The Soul of the Collection

This is where the Bible gets deeply personal. It’s not about nations or laws; it’s about the human condition.

Job asks why bad things happen to good people and never really gives a "neat" answer. It’s uncomfortable. Psalms is the ancient hymnal—150 poems ranging from "God is great" to "I hate my life, where are you?" Proverbs is the common-sense advice your grandpa would give you.

👉 See also: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

Then there’s Ecclesiastes. It’s the "existential crisis" book. The author basically says everything is "hevel"—vapor or smoke. You work, you die, and someone else spends your money. It’s surprisingly modern. And Song of Solomon? It’s a series of love poems that are so steamy that some ancient rabbis didn't even want young people reading it.

The Major and Minor Prophets

When you look at the list books of Old Testament, the Prophets take up a huge amount of space. We call them "Major" and "Minor" only because of the length of the scrolls, not because one is more important than the other. Isaiah is a massive 66 chapters. Obadiah is one page.

Isaiah is the visionary. Jeremiah is the "weeping prophet" because he watched his city burn down. Lamentations is his actual funeral dirge for Jerusalem. Then you have Ezekiel, who had some of the strangest visions in literature—wheels in the sky and valleys of dry bones coming to life. Daniel blends history with apocalyptic dreams, featuring lions' dens and giant statues.

The "Minor" prophets (the Book of the Twelve) are like a fast-paced montage of warnings and hope:

- Hosea: The prophet told to marry an unfaithful woman as a living metaphor.

- Joel: Locust plagues and the "Day of the Lord."

- Amos: A shepherd yelling at rich people for stepping on the poor.

- Obadiah: A short, sharp message to the nation of Edom.

- Jonah: The guy who got swallowed by a fish because he didn't want to do his job.

- Micah: A call for justice and mercy.

- Nahum: The downfall of Nineveh.

- Habakkuk: A dialogue with God about why evil people win.

- Zephaniah: A warning of coming judgment.

- Haggai: "Finish building the Temple already!"

- Zechariah: Wild visions of horsemen and lampstands.

- Malachi: The final word, dealing with corruption and the promise of a messenger.

The Big Confusion: Why the Order Matters

Here’s the thing. If you pick up a Jewish Bible (the Tanakh), it ends with 2 Chronicles. The last word is an invitation to go back home to Jerusalem. It’s an ending of return.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

But the Christian list books of Old Testament ends with Malachi. Why? Because Malachi ends with a prophecy about a "messenger" who will prepare the way. It’s a cliffhanger. By putting Malachi last, the Christian editors were setting the stage for the New Testament and the arrival of John the Baptist. Same books. Different order. Totally different psychological impact.

Nuance and Translation Gaps

You also have to consider the "Apocrypha" or "Deuterocanonical" books. If you’re Catholic or Orthodox, your list is longer. You’ve got Tobit, Judith, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and Wisdom of Solomon. Protestants dropped these during the Reformation because they weren't in the original Hebrew canon.

It’s a point of massive historical debate. St. Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate), was actually hesitant about including them, but the Church eventually leaned into them. It’s a reminder that this "list" wasn't handed down on a single stone tablet from the sky; it was curated over centuries by people trying to preserve what was most sacred.

Practical Steps for Exploring the Text

Don't just read the list from top to bottom. You'll get stuck in the "Leviticus Bog" and never come out.

Start with the narratives. Read Genesis, then jump to 1 & 2 Samuel. This gives you the "story" of the people.

Mix in the Wisdom. Read one Psalm a day. It keeps the heavy history from feeling too clinical.

Check out the "Minor" Prophets for short bursts. They are punchy, intense, and usually take less than 15 minutes to read.

Use a Study Bible. Look for one with notes by scholars like Robert Alter or John Walton. They explain the cultural context that we miss today—like why "taking off a shoe" was a legal contract or why certain animals were "unclean."

Understanding the list books of Old Testament is about recognizing the layers. It’s a library of law, poetry, history, and raw human emotion. If you look at it that way, it stops being a list and starts being a map of how ancient people tried to make sense of their world.