You’ve probably seen them. Those sleek, computer-generated anatomical models in doctor's offices or on Instagram. They show muscle as bright red, bone as pristine white, and maybe—if they’re fancy—a thin, translucent saran-wrap layer over the top. It looks clean. It looks organized. It’s also a total lie.

If you actually looked at a real, live picture of fascia in the body, you wouldn’t see a tidy plastic wrap. You’d see a chaotic, shimmering, wet web of fibers that looks more like a spiderweb covered in morning dew than a piece of anatomy equipment. For decades, medical students literally cut this stuff away to "get to the good parts." They treated it like packing peanuts in a shipping box. But it turns out the packing peanuts are actually the biological computer that keeps you moving.

The Problem With the "Saran Wrap" Myth

Most people think fascia is just a bag that holds muscles. It’s not. It’s a three-dimensional collagenous matrix that weaves through everything. Literally everything. It surrounds every single muscle fiber, every nerve, every organ, and even dives into the bones. Dr. Jean-Claude Guimberteau, a French hand surgeon, changed everything when he put an endoscopic camera under the skin of a living person.

His footage didn't show the dry, white sheets you see in a textbook. Instead, he captured a "Multimicrovacuolar Collagenic Absorbing System." That’s a mouthful, but basically, it’s a sliding, gliding, chaotic mess of micro-threads that hold fluid.

When you see a standard picture of fascia in the body from a cadaver study, you’re looking at something dead. Dried out. In a living human, fascia is essentially a liquid crystal. It’s saturated with water and hyaluronic acid. This stuff is what allows your skin to slide over your muscles when you twist your arm. Without it, you’d be a statue.

💡 You might also like: Foods to Eat to Prevent Gas: What Actually Works and Why You’re Doing It Wrong

Why Your Lower Back Pain Might Be a Fascia Issue

Let's talk about the Thoracolumbar Fascia. It’s that big, diamond-shaped patch in your lower back. If you look at a medical picture of fascia in the body in that specific region, you’ll see it’s incredibly thick. It’s not just a passive layer; it’s a sensory organ.

In fact, research led by experts like Dr. Robert Schleip has shown that fascia has more nerve endings than muscle. It’s packed with nociceptors (pain sensors) and mechanoreceptors (movement sensors). This is why your back might hurt even if an MRI shows your spine and discs are perfectly fine. If that fascia becomes "fuzz"—a term popularized by anatomist Gil Hedley—it gets sticky.

Imagine two pieces of silk sliding against each other. That’s healthy fascia. Now imagine those same pieces of silk with a layer of dried honey between them. That’s what happens when you don't move. The fibers bond together. They dehydrate. When you finally try to move, the fascia yanks on those nerve endings. It hurts. It’s not a "pulled muscle" in the traditional sense; it’s a snagged web.

The Living Matrix: Collagen and Elastin

What are you actually looking at in a picture of fascia in the body? It’s mostly collagen (for strength) and elastin (for stretch).

📖 Related: Magnesio: Para qué sirve y cómo se toma sin tirar el dinero

- Type I Collagen: This is the steel cable. It’s what gives fascia its tensile strength.

- Elastin: This is the rubber band. It lets the tissue snap back after you move.

- Ground Substance: This is the "goo." It’s a gel-like substance that keeps the fibers lubricated.

If you’re sedentary, the "goo" becomes more like "glue." This is why you feel stiff in the morning. Your body has spent eight hours being still, and the fluid in your fascia has thickened. Movement literally thins that fluid out, turning the glue back into a lubricant. It’s a process called thixotropy. Think of it like a bottle of ketchup—you have to shake it or move it to get it to flow.

The Controversy of "Fascial Lines"

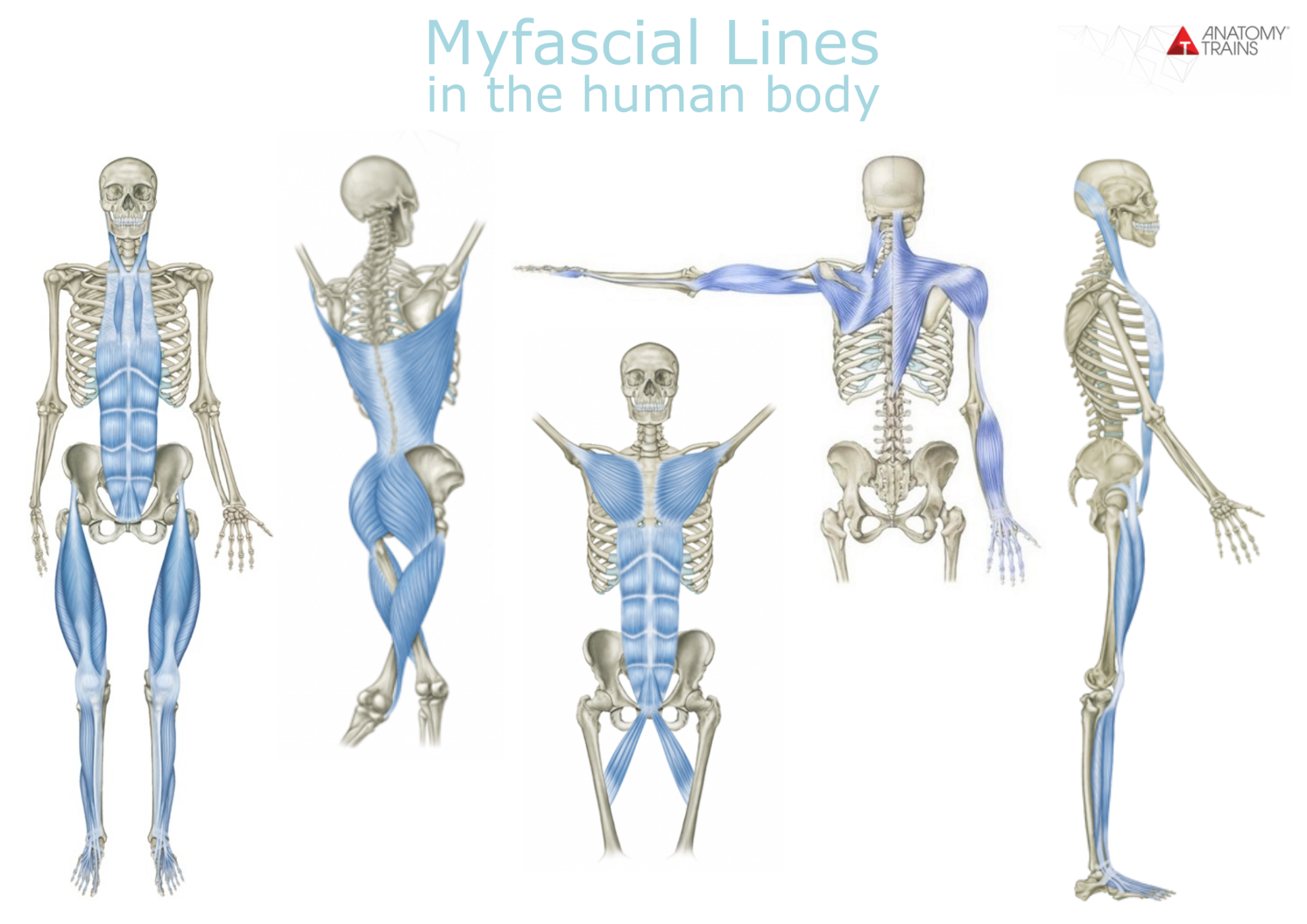

You might have heard of Tom Myers and his book Anatomy Trains. He suggests that fascia doesn't just wrap muscles but forms long, continuous tracks from your toes to your forehead.

While the imagery is compelling, it's a bit controversial in the scientific community. Some researchers argue that while these connections exist, we shouldn't treat them as literal "cables." However, if you look at a picture of fascia in the body during a specialized dissection, you can see the Superficial Back Line—a continuous sheet of tissue that connects the soles of your feet to your calves, hamstrings, sacrum, and all the way up to your brow.

This explains why some people find that rolling a tennis ball under their foot magically helps them touch their toes. You aren't stretching your hamstrings; you’re releasing the tension in the entire "train" of fascia.

👉 See also: Why Having Sex in Bed Naked Might Be the Best Health Hack You Aren't Using

It’s Not Just About Stretching

Everyone wants to "stretch" their fascia. But honestly? Fascia is incredibly strong. You aren't going to lengthen a collagen fiber by holding a yoga pose for thirty seconds. It would be like trying to stretch a seatbelt with your bare hands.

True fascial change happens through hydration and varied movement. Repetitive motion—like running the exact same way on a treadmill every day—can actually cause fascia to thicken in a way that limits mobility. You need "shear." You need to move in weird angles. Think of it like "wringing out" a sponge. You want to squeeze the old fluid out so fresh, nutrient-rich fluid can rush back in.

Real Insights for Fascial Health

If you want to keep your internal web healthy, looking at a picture of fascia in the body is just the start. You have to understand how it reacts to your environment.

- Hydration isn't just drinking water. You have to move to get that water into the tissue. Dehydrated fascia is brittle. Brittle fascia tears.

- Stop the "no pain, no gain" mentality with foam rolling. If you press too hard, your nervous system perceives a threat and causes the fascia to contract (yes, fascia can contract on its own—it contains myofibroblasts). Use a "gentle melting" sensation rather than trying to crush your IT band.

- Bounce a little. Fascia loves elastic recoil. Small, bouncy movements—like jumping rope or light plyometrics—help train the elastin fibers.

- Vary your geometry. Reach for things at different angles. Sit on the floor. Change your posture often.

Fascia is essentially the "system of systems." It’s the infrastructure of your physical being. When it’s healthy, you feel light and springy. When it’s bound up, you feel like you’re wearing a wet suit that’s two sizes too small. Respect the web.

Next Steps for Better Mobility:

Start by incorporating proprioceptive variety into your daily routine. This doesn't mean a new workout; it means changing how you do normal things. Brush your teeth while standing on one leg to engage the stabilizers in your feet and hips. Instead of static stretching, use slow, oscillating movements to "glide" your fascial layers against one another. Finally, prioritize interstitial hydration by taking short "movement snacks" every 30 minutes to prevent the fascial "fuzz" from setting in during long periods of sitting. This keeps the tissue supple and prevents the long-term thickening that leads to chronic stiffness.