You’ve probably seen them in textbooks. A bunch of pipes, a big concrete dome, and some steam coming out of a tower. Honestly, most people look at a nuclear power reactor diagram and assume it’s basically just a giant, dangerous tea kettle. In a way, they aren't wrong. At its core, nuclear power is just a very sophisticated method of boiling water to turn a turbine. But the devil is in the details, and those details are what keep the lights on—and the radiation contained.

People get confused because there isn't just "one" type of reactor. If you’re looking at a diagram of a Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR), it’s going to look fundamentally different from a Boiling Water Reactor (BWR) or a CANDU model. It’s like comparing a diesel engine to a gasoline one; they both move the car, but the plumbing is different.

The Core Components You’ll See in Every Nuclear Power Reactor Diagram

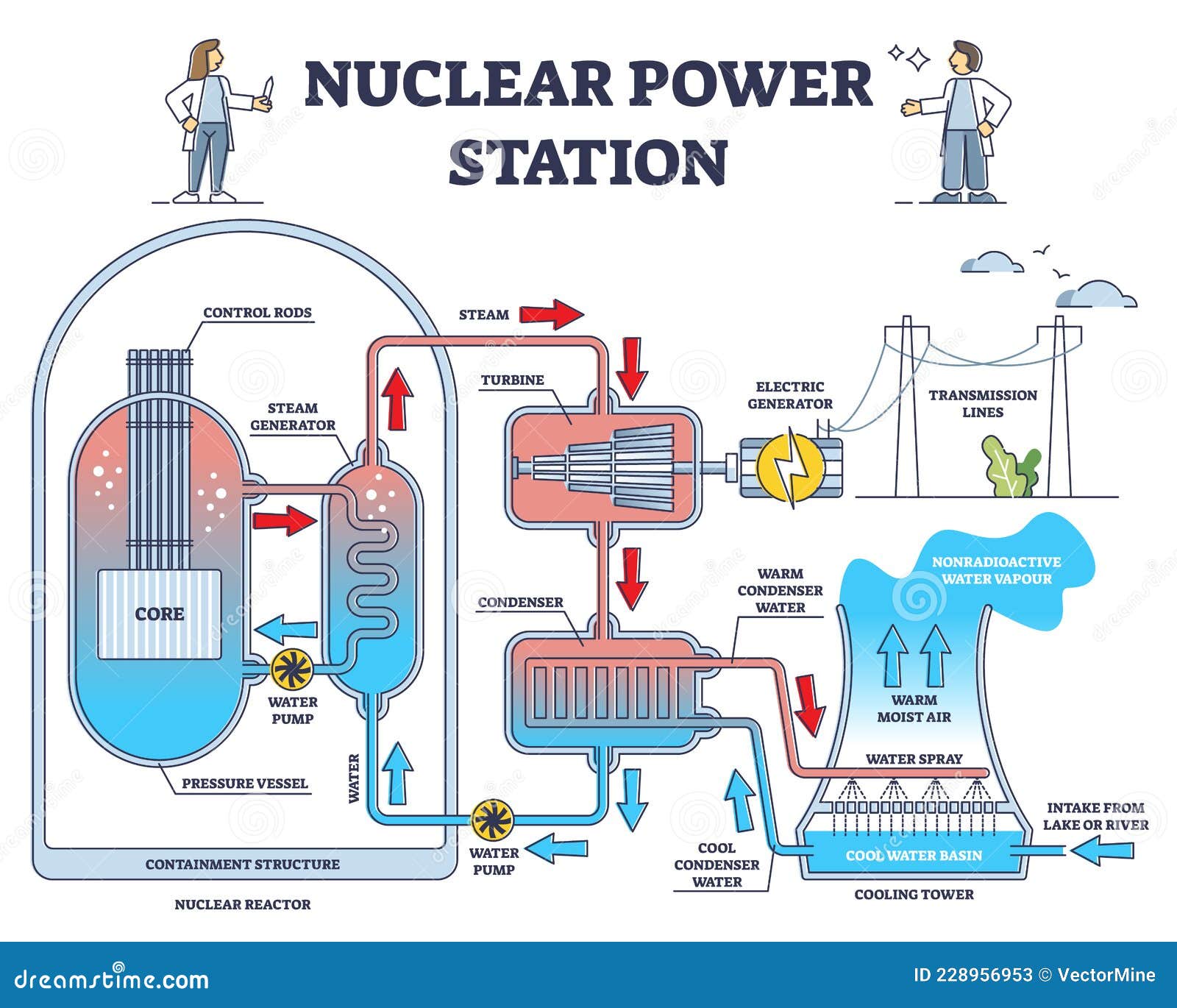

Despite the variety, some things are universal. Every nuclear power reactor diagram starts with the core. This is where the magic—or the physics, rather—happens. Inside the core, you have fuel assemblies. These aren't just loose piles of uranium. They are meticulously engineered rods, usually filled with ceramic pellets of Uranium-235.

When a neutron hits a U-235 nucleus, it splits. This is fission. It releases a massive amount of heat and more neutrons. If you don't control those neutrons, things get spicy way too fast. That’s why every diagram features "control rods." Think of these as the brakes on a car. Made of materials like boron or cadmium, they soak up neutrons. Slide them in, the reaction slows down. Pull them out, and the power climbs. It’s a delicate balance that operators at plants like Byron or Wolf Creek manage every single second.

The Moderator: The Unsung Hero

Here is something most people miss. To keep a reaction going, neutrons actually need to slow down. Fast neutrons are bad at hitting the "target" nucleus. So, you need a moderator. In most American reactors, this is just regular old water. In others, it’s graphite or heavy water. If a diagram shows a "moderator," it's explaining why the physics doesn't just stop or explode instantly. It’s the "Goldilocks" component that makes the energy usable.

Why the Loops Matter

If you look at a nuclear power reactor diagram for a PWR, you’ll notice two distinct loops of water. This is a crucial safety feature. The water that touches the radioactive fuel (the primary loop) never actually touches the turbine. It stays inside the containment building. It’s under immense pressure—about 155 atmospheres—so it doesn't boil even though it's screaming hot, often over 300°C.

This hot, high-pressure water goes to a heat exchanger. It’s basically a radiator. It gives its heat to a second loop of water. This second loop is the one that turns into steam and spins the turbine. By keeping these separate, engineers ensure that if a pipe leaks in the turbine hall, it isn't radioactive water hitting the floor. It’s just steam.

Boiling Water Reactors (BWRs) are simpler, but also a bit more "intimate" with the radiation. They only have one loop. The water boils right there in the reactor vessel and goes straight to the turbine. It’s more efficient, but it means the entire turbine hall becomes a high-radiation zone during operation. You can see this clearly when you compare the two side-by-side in a nuclear power reactor diagram. The BWR diagram looks much cleaner, with fewer pipes, but the maintenance is a whole different beast.

👉 See also: Why Every Diagram of How a Turbo Works Usually Misses the Point

Cooling Towers: The Biggest Misconception

We have to talk about the towers. You know the ones. The iconic, hourglass-shaped concrete giants. Most people see those in a nuclear power reactor diagram and think that’s where the "nuclear" stuff is. Nope. Those are just cooling towers.

Their only job is to cool down the water from the condenser so it can be reused. The "smoke" you see coming out? Pure water vapor. It’s basically a man-made cloud. In fact, many plants don't even have them. If a plant is near a massive body of water, like the Seabrook Station in New Hampshire, they just use ocean water for cooling and skip the towers entirely. If you see a diagram without the big curvy towers, don't panic. It just means there's a river or ocean nearby doing the heavy lifting.

The Containment Structure: The Last Line of Defense

Look at the thickest line on your nuclear power reactor diagram. That’s the containment building. This isn't just a shed. We’re talking several feet of steel-reinforced concrete. It is designed to withstand a direct hit from a literal jet airliner.

Inside this dome, the pressure is actually kept slightly lower than the outside atmosphere. Why? Because if there’s a tiny crack, air leaks in, rather than radioactive gas leaking out. It’s a simple pressure trick that acts as a massive safety net. When you see the "containment" label on a diagram, realize that it’s the most expensive and robust part of the entire facility.

Modern Variations: SMRs and Beyond

The diagrams are changing. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are the new kids on the block. Companies like NuScale are designing reactors that are tiny compared to the behemoths of the 1970s.

In an SMR nuclear power reactor diagram, everything is integrated. The steam generators and the core are often in the same vessel. They use natural circulation. This means they don't even need pumps to move the water; gravity and heat differentials do it for them. If the power goes out, the physics of the reactor naturally shuts it down and cools it off without any human intervention. It's "passive safety."

👉 See also: How to Transfer from One Mac to Another Without Losing Your Mind (or Data)

Then there are Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs). These diagrams look wild. Instead of solid fuel rods, the fuel is actually dissolved in liquid salt. If the reactor gets too hot, a "freeze plug" at the bottom melts, and the liquid fuel drains into a storage tank where it naturally cools down and stops reacting. No meltdown possible. It’s a total shift in how we visualize nuclear safety.

Why We Still Use Old Designs

You might wonder why we still use 50-year-old designs if SMRs are so cool. It’s basically about money and regulation. Building a new nuclear plant is a multi-billion dollar bet. Most of the plants operating today, like those managed by Exelon or NextEra Energy, were built when the regulatory environment was different. They are workhorses. They have high capacity factors, meaning they run 90% of the time. Solar and wind can't do that yet without massive batteries.

Understanding the Risks Through the Diagram

When things go wrong, the nuclear power reactor diagram helps explain why. In Three Mile Island, a valve got stuck. The diagram shows where that valve was—in the secondary loop. Because the operators couldn't "see" what was happening in the primary loop, they made moves that made the problem worse.

At Chernobyl, the diagram would show a RBMK reactor. These used graphite as a moderator and had a "positive void coefficient." Basically, if the water turned to steam, the reaction sped up instead of slowing down. Most Western reactors have a "negative void coefficient." If the water disappears, the reaction dies. It’s a fundamental design difference that makes a Chernobyl-style explosion physically impossible in a PWR or BWR.

Actionable Insights for Reading Reactor Schematics

If you're looking at a nuclear power reactor diagram for school, work, or just out of curiosity, keep these points in mind to decode what you're seeing:

✨ Don't miss: Finding a macbook air 13 case that actually protects your laptop without ruining it

- Follow the water: Find where the water turns to steam. If it happens in the core, it's a BWR. If it happens in a separate heat exchanger, it's a PWR.

- Identify the "Cold Leg" and "Hot Leg": These are the pipes leading to and from the reactor vessel. The hot leg is always the one coming out of the top of the core.

- Look for the Pressurizer: In a PWR diagram, there’s a small tank that looks like a hat on the primary loop. That’s the pressurizer. It keeps the water from boiling.

- Check the redundant systems: Real engineering diagrams will show multiple "trains" of cooling. If one pump fails, two more are waiting in the wings.

- Distinguish between the "Nuclear Island" and the "Balance of Plant": The nuclear island is the radioactive stuff inside the dome. The balance of plant is the regular electrical stuff like turbines and transformers that you'd find in a coal or gas plant.

Nuclear power is complicated, sure. But the basic layout hasn't changed much in decades because the physics of boiling water is pretty consistent. Whether it's a massive Gen III+ reactor or a tiny modular unit, the goal is always the same: controlled heat, converted to motion, converted to the electricity charging your phone right now.

Next time you see a nuclear power reactor diagram, don't just see a mess of lines. Look for the loops. Find the containment. Trace the path from the uranium pellet to the power line. Once you see the logic of the heat transfer, the whole thing stops being a "black box" and starts being a masterpiece of mechanical engineering.