You’ve seen them everywhere. Those swirling, muscular fish tattooed on biceps or painted onto silk scrolls. But honestly, sitting down to create a drawing of a carp is a massive reality check for most artists. It looks easy until you realize you’re basically trying to draw a flexible armored tube that’s constantly in motion.

It’s about the flow. If you get the curve of the spine wrong by even a few millimeters, the whole thing looks like a dead trout rather than a powerful creature fighting its way up a waterfall.

Most people start with the head. That’s a mistake. When you’re tackling a drawing of a carp, particularly the Cyprinus rubrofuscus (the hardy species we usually call Koi), you have to think about the gesture first. It’s all about that "S" curve.

The Anatomy Most People Get Wrong

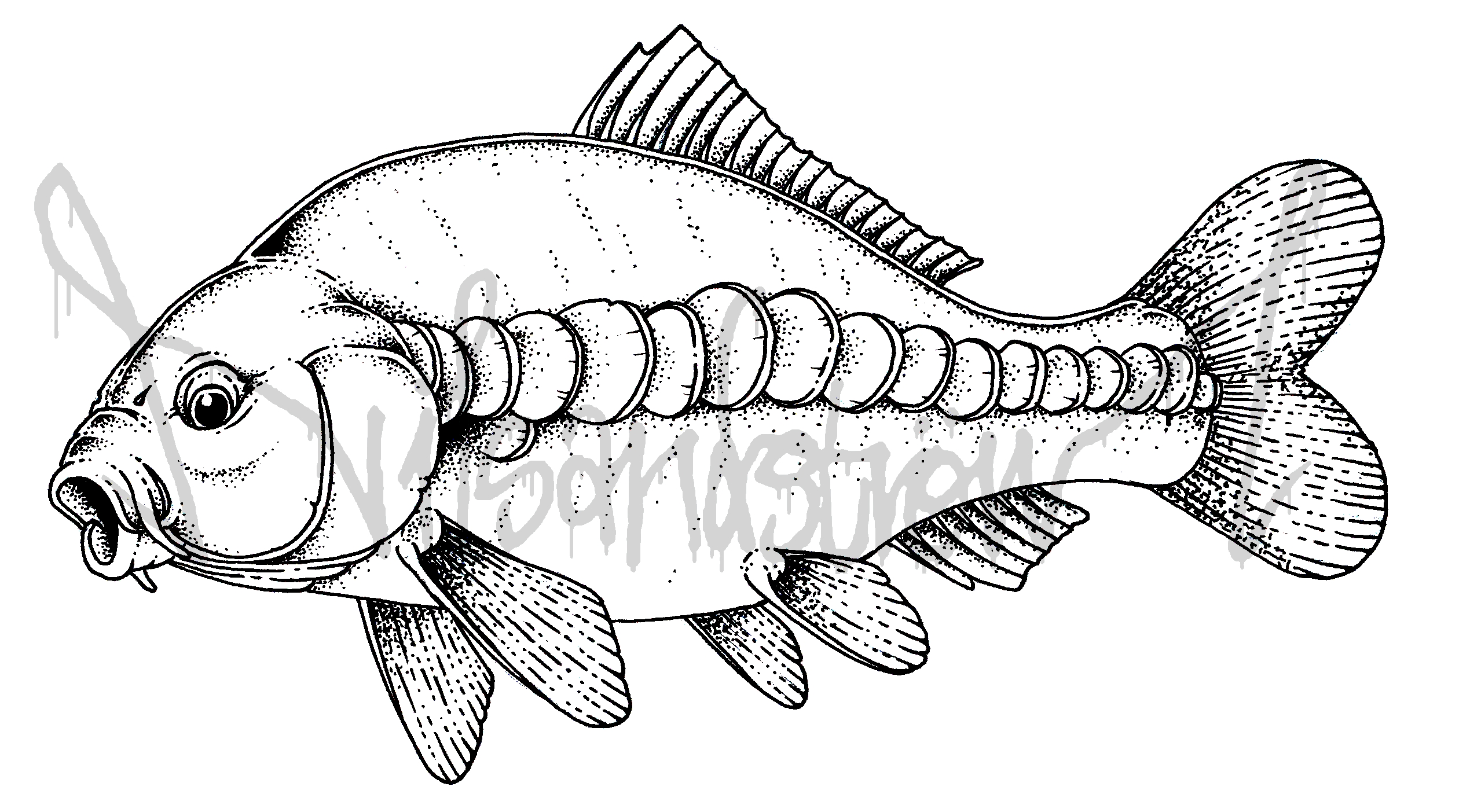

The skeletal structure of a carp is surprisingly complex. They aren't just ovals with fins. A real carp has a chunky, heavy-set body. If you look at the work of masters like Katsushika Hokusai, you’ll notice they emphasize the "hump" just behind the head. This isn't just an artistic choice; it’s a biological reality of how these fish build muscle to navigate high-pressure currents.

Let’s talk about the barbels. Those little whisker-like appendages near the mouth? They aren't just for show. They’re sensory organs. In a realistic drawing of a carp, these should look soft and fleshy, not like stiff wires. They usually hang downward or trail slightly back if the fish is "moving" in your piece.

Then there’s the eye. It’s not a human eye. It doesn't have a visible white sclera in the way ours do. It’s a dark, glossy orb that reflects the environment. If you add a tiny white "catchlight" in the wrong spot, you lose the underwater effect instantly.

Scale Logic and the "Chainmail" Trap

Scale patterns are where 90% of artists give up. They start off strong near the head, get bored by the mid-section, and by the tail, it looks like a mess of scribbles. Don't do that.

Think of the scales as a grid that wraps around a cylinder. They follow the perspective. The scales on the side facing you are large and wide, while the ones wrapping toward the belly or the spine should appear narrower and more compressed. This is what creates the 3D effect.

Technically, you’re looking at a "cycloid" scale pattern. They overlap like roof shingles. If you’re working with graphite, vary your pressure. The scales near the lateral line—that faint line running down the side of the fish—often catch the light differently because of the sensory pores located there.

Why the Fins Are the Soul of the Piece

If the body is the engine, the fins are the sails. For a drawing of a carp to feel alive, the fins need to look translucent. This is especially true for the caudal fin (the tail).

In traditional Japanese Irezumi style, the fins are often depicted with sharp, rhythmic lines to show movement. But if you’re going for realism, you need to study the fin rays. These are the bony "ribs" inside the fin. They aren't perfectly straight. They branch out as they reach the edge of the fin, almost like the veins in a leaf.

- The dorsal fin (on the back) usually has a stiff, serrated leading ray.

- The pectoral fins (near the "shoulders") act like rudders.

- Flowing, "butterfly" varieties have much longer, delicate fins that behave like silk in water.

I’ve spent hours watching carp in ponds. They don't move their whole bodies constantly. They glide. A single flick of the pectoral fin can rotate the entire fish. When you’re sketching, try to capture that tension. One fin might be tucked tight against the body while the other is flared out wide. That’s how you tell a story with a single image.

Composition and the "Water Effect"

A common mistake is drawing the fish in a vacuum. A drawing of a carp needs context. Even if you aren't drawing a full pond, you need to imply the water.

How? Bubbles. Swirls. Distortions.

Water refracts light. If part of the tail is deeper in the water than the head, it should be slightly less detailed and cooler in tone. Use "lost and found" edges. This is a technique where some outlines of the fish literally disappear into the background, letting the viewer’s eye finish the shape. It creates a sense of depth that a hard outline never could.

The Cultural Weight of Your Sketch

You aren't just drawing a fish. You’re engaging with a symbol that’s over a thousand years old. In Chinese mythology, the carp that could leap the "Dragon Gate" on the Yellow River was transformed into a dragon. This is why so many drawings of carp include splashing water and steep inclines. It represents perseverance.

If you’re drawing a Koi specifically, the colors matter. A Kohaku (white body, red spots) carries a different vibe than a Hajiro (black body with white fin tips). Even in a black-and-white pencil drawing, you can suggest these colors through value. The red spots should be a medium grey, while the white areas are the bright highlights of the paper itself.

Practical Steps to Master the Form

Stop trying to draw a "fish." Start drawing shapes.

Begin with a curved centerline. This represents the spine. Then, build the volume around it using "rib" circles. This ensures your carp doesn't look flat. Once you have the 3D form, map out the "insertion points" for the fins. Most beginners attach fins to the outline of the fish, but they actually grow out from the musculature slightly inside the body.

🔗 Read more: Why Black People Make Love Differently: Culture, Connection, and Intimacy Explained

Next Steps for Your Practice:

- Gesture Mapping: Spend ten minutes doing 30-second "bean" shapes. Just capture the curve and the direction of the head.

- Scale Grid: Practice drawing a cylinder and wrapping a diamond grid around it. This is the muscle memory you need for the body.

- Negative Space: Look at a photo of a carp and try to draw only the water around it. It sounds weird, but it’s the fastest way to understand the silhouette.

- Value Study: Focus on the transition from the dark back to the pale belly. This gradient is what gives the fish its weight.

Don't worry if the first few look like bloated goldfish. Carp are chunky. They’re supposed to look powerful, not sleek like a barracuda. Keep your lines fluid and remember that in nature, there are no perfect straight lines. The more you let your hand flow with the "water," the more natural the result will feel.