Honestly, it’s hard to watch Richard Donner’s 1997 film Conspiracy Theory in the 2020s without feeling a little bit itchy. You’ve got Mel Gibson playing Jerry Fletcher, a taxi driver who isn't just "out there"—he’s basically living in a self-made prison of newspaper clippings and padlocked refrigerators. Back in the late nineties, this was seen as a fun, slightly paranoiac thriller. Fast forward to now? It feels less like a quirky character study and more like a terrifyingly accurate blueprint of how the internet has reshaped our collective brain.

The movie didn't just capitalize on a trend. It defined a vibe.

We’re talking about a time when The X-Files was the biggest thing on TV and everyone was looking at the millennium with a mix of excitement and "oh no, the computers are going to kill us" dread. But Conspiracy Theory did something different. It took the concept of the "lone nut" and asked: What if the guy who thinks the water supply is poisoned is actually right?

The Anatomy of Jerry Fletcher’s Madness

Jerry is a mess. That’s the core of the conspiracy theory movie 1997 experience. He’s a New York City cabbie who spends his nights rambling to his passengers about NASA, the UN, and various secret agencies. His apartment is a fortress. He literally has a canister of orange juice locked inside a box with a combination lock. It’s a great visual gag, but it’s also a deeply sad look at what happens when someone loses their grip on reality—or has reality hidden from them by force.

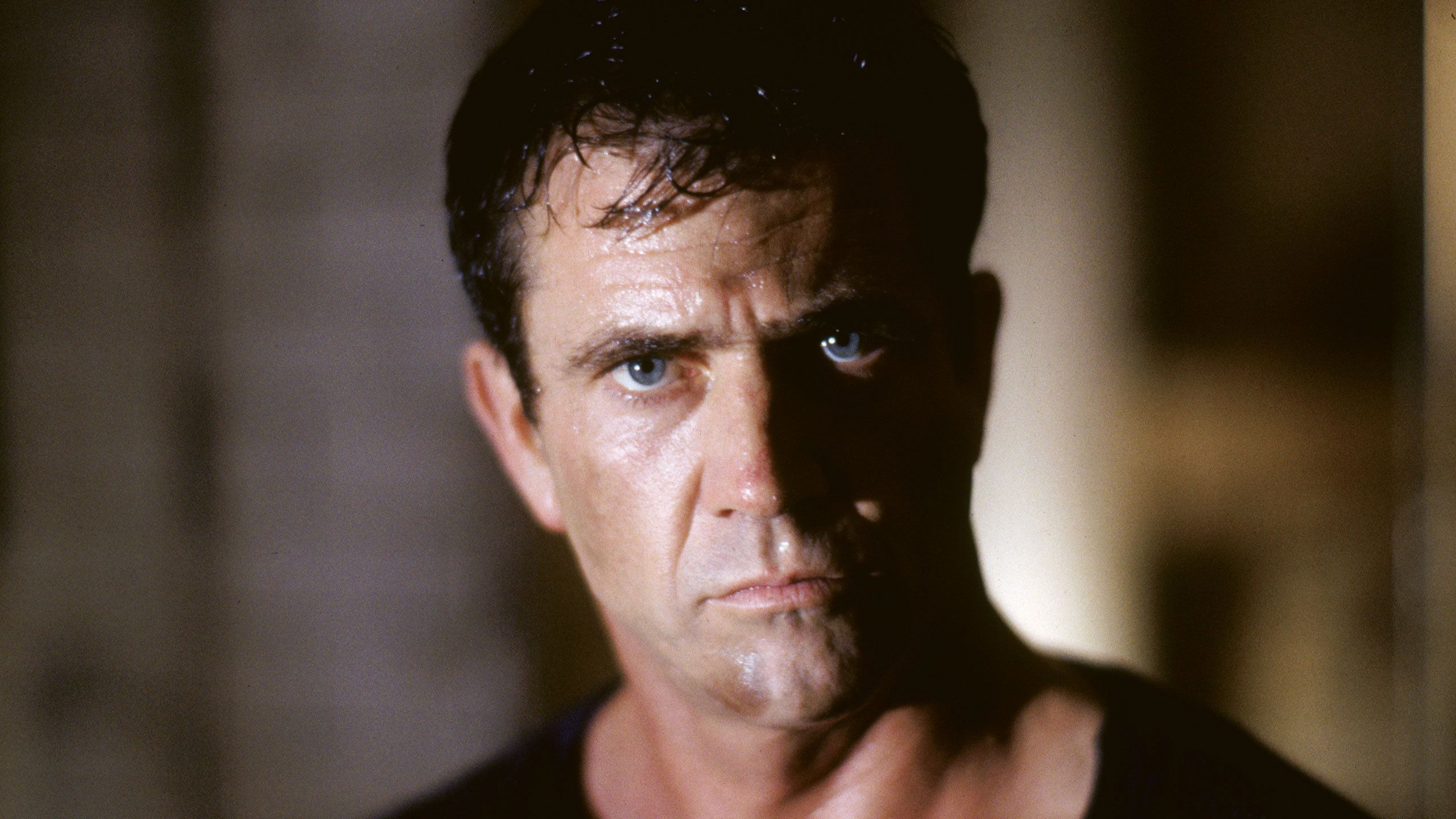

Gibson plays it with this frantic, high-wire energy. It’s a lot. You’ve got the stuttering, the wide eyes, and that constant physical restlessness. Then you have Julia Roberts as Alice Sutton, a Justice Department attorney who becomes the unwilling focus of Jerry’s obsession.

The dynamic is weird. Looking back, the "stalker" vibes are pretty heavy, but the movie frames it through the lens of a mystery. Jerry doesn't know why he’s drawn to her, just that he is. And Alice, who is grieving her father’s unsolved murder, represents the "rational" world that Jerry is trying to penetrate. It’s a classic 90s setup: the wild card meets the suit.

What’s fascinating is how the film treats Jerry’s newsletter. He publishes "Conspiracy Theory," a mimeographed zine that he mails out to five people. Just five. In 1997, that was the limit of a fringe voice. Today, Jerry would have a Substack with 50,000 subscribers and a three-hour podcast sponsored by a vitamin company. The scale has changed, but the psychology is identical.

Why the MKUltra Connection Matters

If you’ve seen the film, you know it isn't just about general paranoia. It’s specifically about MKUltra. This isn't a spoiler—the movie reveals pretty early on that Jerry’s fractured mind is the result of actual government experimentation.

This is where the film bridges the gap between fiction and horrifying fact. MKUltra was a real CIA program that ran from the 1950s through the early 70s. They were looking for mind control techniques. They used LSD, sensory deprivation, and hypnosis on unwitting subjects. When Conspiracy Theory 1997 hit theaters, this wasn't ancient history; it was a scar on the American psyche that was still relatively fresh in the public consciousness.

📖 Related: Why Superman vs the Elite Still Matters for Every DC Fan

- The movie uses the "Gerhardt" character (played with chilling calm by Patrick Stewart) to represent the institutionalized evil of these programs.

- He isn't a mustache-twirling villain; he’s a bureaucrat.

- That’s what makes the "conspiracy theory movie 1997" so effective—the villains believe they are doing necessary work for the state.

People often forget that the film was a massive production. We’re talking an $80 million budget in 1997 dollars. That’s huge. Warner Bros. wasn't making an indie flick; they were making a blockbuster about state-sponsored trauma.

Breaking Down the Donner-Gibson Synergy

Richard Donner and Mel Gibson were the ultimate duo of that era. They’d already done the Lethal Weapon series. They had a shorthand. You can see it in the way the camera moves—Donner knows exactly how to capture Gibson’s frantic movements without losing the audience.

The cinematography by John Schwartzman is also worth a shout-out. New York looks cold. Not "pretty" cold, but gritty, blue-tinted, and claustrophobic. Even the wide shots of the city feel like they’re hiding something. It’s a far cry from the glossy, hyper-saturated NYC we see in Marvel movies today.

One of the best scenes is the escape from the hospital. Jerry is strapped to a gurney, sedated, and he still manages to bite a guy’s nose off. It’s visceral. It’s messy. It’s quintessentially Donner. He wasn't afraid of making his protagonist look ugly or desperate.

The Problem With the Ending (Maybe)

If there’s a critique of the conspiracy theory movie 1997, it’s that it tries to have its cake and eat it too. The first two acts are a tight, psychological thriller. The third act? It becomes a full-blown action movie. Helicopters, gunfights, the whole nine yards.

Some critics at the time, like Roger Ebert, felt it leaned too hard into the "Hollywood" of it all. Ebert gave it two stars, saying the movie became a "conventional chase thriller" that lost interest in its own fascinating premise. He wasn't entirely wrong. When the mystery is solved, some of the tension evaporates. However, the chemistry between Roberts and Gibson carries it through the finish line.

Real-World Parallels That Refuse to Die

We have to talk about the "predictive" nature of this film. In the movie, Jerry talks about a secret group planning an earthquake. People laughed. Then, years later, you have folks on social media genuinely convinced that HAARP (the High-frequency Active Auroral Research Program) is controlling the weather.

✨ Don't miss: Why That Antoni Porowski Netflix Psycho Video Still Ranks as a Top-Tier Marketing Fever Dream

Jerry mentions the "black helicopters." This was a huge talking point for the militia movements of the 90s. The movie didn't invent these ideas; it curated them. It took the fringe flotsam of the USENET boards and put it on a 40-foot screen.

But the most "1997" thing about it is the technology. Jerry uses a computer that looks like a brick. He relies on physical newspapers. He has to physically mail his newsletter. There’s a tactile nature to his paranoia. He’s surrounded by paper. Today, that paranoia is digital. It’s in the algorithms. It’s much harder to lock your "digital" orange juice in a box.

A Legacy of Suspicion

Is Conspiracy Theory a masterpiece? Probably not. But it is a fascinating time capsule. It captures the moment right before the internet changed everything. It’s also one of the few big-budget films that actually treats the victims of government experimentation with some level of empathy, even if it wraps it in an action-adventure package.

The film's influence can be seen in everything from The Bourne Identity to Mr. Robot. The idea of the "unreliable narrator" who turns out to be the most reliable person in the room is a trope that we haven't gotten tired of yet.

If you’re going to revisit it, look for the small details. Look at how Jerry’s apartment is organized. Notice the way the soundtrack—composed by Wojciech Kilar—uses sharp, stabbing strings to mimic Jerry’s anxiety. It’s a masterclass in building a mood of sustained unease.

How to Watch Like a Pro

If you're diving back into this 90s classic, do yourself a favor and watch it through a modern lens. Don't just look for the plot holes. Look at the way the film handles the idea of "truth."

- Watch the background. Donner loved cluttering his frames with posters and signs that hint at Jerry's obsessions.

- Pay attention to the color palette. Notice how the world gets "warmer" as Alice starts to believe Jerry.

- Check out the "Catcher in the Rye" motif. It’s a classic trope for "triggered" assassins, but the way the movie uses it as a tracking device for the villains is actually pretty clever.

The best way to experience the conspiracy theory movie 1997 is to remember that in 1997, we thought the biggest threat was a secret group in a dark room. Now we know the biggest threat is often just the sheer volume of noise we produce ourselves.

💡 You might also like: Why The Undertaker at WrestleMania Is Still the Greatest Feat in Sports Entertainment

The movie ends with a bit of a "is he or isn't he" vibe regarding Jerry's survival and his continued surveillance of Alice. It’s a bittersweet note. It suggests that even if you win, you can never really "leave" the conspiracy. You just become a different part of it.

To get the most out of a rewatch, pair it with a documentary on the real MKUltra or the COINTELPRO operations of the FBI. Seeing how close the fiction sits to the reality makes the film's campier moments feel a lot more grounded. You’ll realize that Jerry Fletcher wasn't just a character; he was a manifestation of a very real American anxiety that hasn't gone away—it’s just moved into our pockets.

Check the credits for the song "Can't Take My Eyes Off You." It’s used throughout the film as a trigger and a theme. By the end, that cheerful pop song feels deeply ominous. That’s the magic of the 1997 film: it takes the familiar and makes it feel dangerous. Use a high-quality streaming service to catch the grain of the 35mm film; it adds a layer of grit that modern digital "conspiracy" thrillers often lack. Focus on the practical stunts, especially the chimney climb, which shows the physical toll of Jerry's desperation. This isn't just a movie about ideas; it's a movie about the physical weight of knowing too much.