You walk into the Museum of Modern Art in Midtown Manhattan, and there it is. It’s smaller than you’d expect, tucked away among other heavy hitters of the 20th century. But Broadway Boogie Woogie doesn't sit still. It vibrates. It’s basically a map of a city that was vibrating with jazz, neon lights, and a frantic energy that Piet Mondrian had never really experienced before he landed in New York in 1940. Honestly, for a guy who spent decades painting rigid black lines and static primary colors, this painting was a massive "pivot" before people even used that word. It's the visual equivalent of a heart rate monitor after three espressos.

Most people see Mondrian as the guy who made those minimalist rectangles you see on high-end tissue boxes or Yves Saint Laurent dresses. But Broadway Boogie Woogie is different. It’s his final masterpiece. It’s the sound of the 1940s translated into oil on canvas.

The Chaos Behind the Squares

When Mondrian fled Europe during World War II, he wasn't just moving to a new apartment. He was escaping a continent that was literally falling apart. He arrived in New York and fell head-over-heels for the grid. The streets. The lights. The yellow cabs. It was the first time in his career that his internal artistic logic—the obsession with the right angle—matched the external world perfectly.

You've gotta understand how rigid he used to be. For years, he followed "Neo-Plasticism," which was basically a strict set of rules. No diagonals. No curves. Only primary colors. Then he hears boogie-woogie music in a Harlem club.

Suddenly, those thick black lines he’d used for twenty years? Gone.

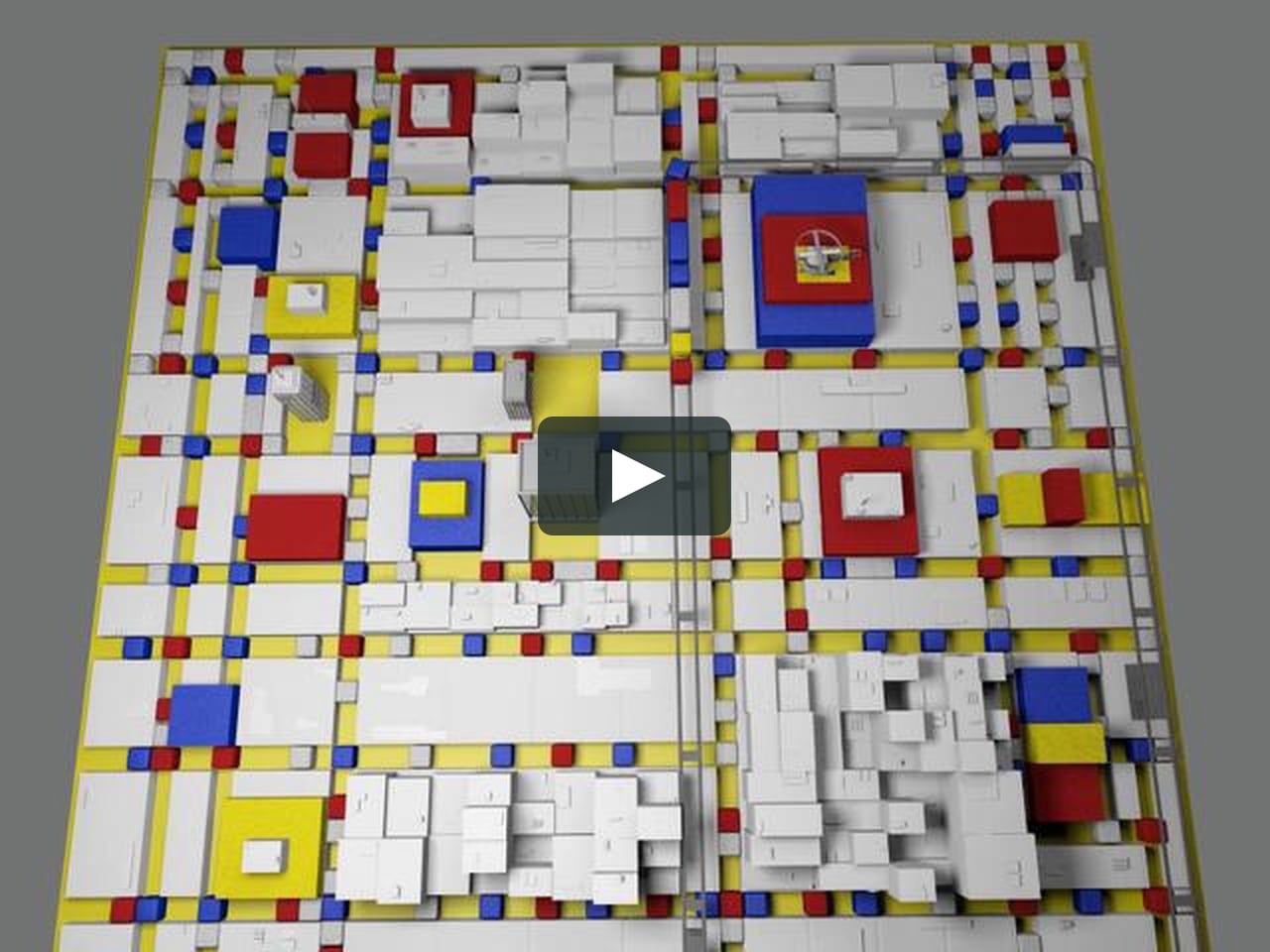

He replaced them with lines made of colored blocks. Yellow, red, blue, and gray squares are stitched together like a digital circuit board or a frantic street map. If you stare at it long enough, the yellow lines start to pulse. That wasn't an accident. Mondrian was trying to capture the "optical flicker" of New York at night. It’s the blinking lights of Broadway theaters and the staccato rhythm of a piano player’s left hand.

How Broadway Boogie Woogie Broke All the Rules

For the art history purists, this painting was a bit of a shock. It felt like Mondrian was loosening his tie.

Think about it.

He spent his whole life trying to reach "universal beauty" through total stillness. Then he gets to New York, sees a taxi, hears some jazz, and decides that movement is the ultimate truth. In Broadway Boogie Woogie, the balance is dynamic, not static.

There’s no central point.

Your eye just jumps from one little red square to a blue one, then follows a yellow line until it hits a larger block of color that feels like a city park or a building. It's decentralized. This was huge. It influenced everyone from the Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock—who, funnily enough, Mondrian actually helped discover—to modern web designers who use grid-based layouts today.

Why the Colors Look Different

Wait, look closer at the actual paint.

If you see it in person at MoMA, you’ll notice the texture isn't perfect. Mondrian was a tinkerer. He didn't just paint it in one go. He used pieces of colored tape to plan the composition, moving them around for months until the "rhythm" felt right. There are layers of paint that show he was struggling to get the exact vibration he wanted.

Some critics, like Robert Hughes, noted that this painting represents a "triumph of the spirit" over the darkness of the war. While Europe was burning, Mondrian was painting the most optimistic, bright, and rhythmic thing he had ever created. It’s almost a middle finger to the destruction happening across the Atlantic.

The Jazz Connection

You can’t talk about this painting without talking about the music. Mondrian was obsessed. He didn't just like jazz; he lived it. He once said that boogie-woogie was the musical equivalent of his art because it destroyed the melody (the "old way") and replaced it with pure rhythm.

- The Left Hand: In boogie-woogie piano, the left hand keeps a steady, driving bass line. You can see this in the long, continuous yellow lines that frame the canvas.

- The Right Hand: The right hand does the improvisational, jumpy stuff. That’s the little red and blue squares that interrupt the yellow lines.

It’s literally a score you can see.

Honestly, it’s kind of funny thinking about this skinny, elderly Dutch man in a suit, dancing alone in his white-walled studio to record players. But that’s exactly what happened. He was finding a way to make paint do what the music did—move without going anywhere.

The Technical Reality

Let's get into the weeds for a second. The painting is roughly 50 by 50 inches. It’s a square. This is important because it removes the "landscape" or "portrait" bias. It’s an object.

The color palette is restricted, but the way he uses white is brilliant. The white isn't just "background." It’s the space between the buildings. It’s the air. It’s what allows the colors to breathe. If the whole thing was covered in squares, it would be too much. It would be noise. Because of the white space, it’s music.

Some people argue that Broadway Boogie Woogie is actually a map. If you look at it from a bird's-eye view, you can almost see the intersections of 42nd Street. But it’s more than a map. It’s the feeling of being at those intersections. It’s the sensory overload of a 1940s New Yorker who just realized that the future is fast, loud, and incredibly bright.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

If you're looking to actually appreciate this piece or apply its logic to your own life/creative work, here's the play:

Go to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in NYC. Don't just look at the postcard. You need to see the physical height of the paint. The way the yellow interacts with the white ground changes depending on the lighting in the room. Stand about six feet back, then move to two feet. The "flicker" effect only happens when you're at the right distance.

Study the Grid. If you’re a designer or architect, look at how Mondrian creates "weight" without using big shapes. He uses frequency. More small squares in one area make that part of the "street" feel busier. It’s a masterclass in visual hierarchy.

Listen to Albert Ammons or Meade Lux Lewis. These were the guys Mondrian was listening to while he painted this. Put on "Boogie Woogie Stomp" and look at a high-res image of the painting. The connection isn't metaphorical; it's literal. The syncopation in the music is the exact same syncopation in the placement of the blue squares.

💡 You might also like: Weather for Anderson Missouri: What Locals Know That Your App Doesn't

Look for the "Unfinished" Legacy. Mondrian died shortly after finishing this (and left "Victory Boogie Woogie" unfinished). Compare the two. You’ll see how he was moving even further toward breaking the lines apart. Broadway is the bridge between his old, strict style and a future he didn't live to see.

Analyze the lack of Black. For most of his career, black lines were his "skeleton." In this painting, he realized he didn't need them. Use this as a creative prompt: what's the one thing you think is "essential" to your work? Try removing it and see if the work survives. For Mondrian, removing black lines made his work more alive than ever.

The painting remains a reminder that even late in a career, it's possible to completely reinvent yourself. Mondrian was 71 when he finished this. He wasn't looking back; he was looking at the lights of the city and trying to keep up.