You probably remember that old Punnett Square from high school biology. The one where two brown-eyed parents have a 25% chance of producing a blue-eyed baby. It feels clean. It feels mathematical. It’s also mostly wrong. Or at least, it’s a massive oversimplification that ignores how human biology actually works in the real world.

If you’re looking at an eye color genetic chart today, you’re likely trying to predict what your future kid will look like or why you ended up with "hazel" eyes when your siblings have piercing blue ones. The truth is that eye color isn't a single-switch light. It’s more like a complex dimmer system controlled by a dozen different hands at once.

Eye color is polygenic. That’s a fancy way of saying multiple genes are invited to the party. While we used to think it was just about "dominant" versus "recessive," researchers have identified at least 16 different genes that play a role in determining the hue of your iris.

The Big Players: OCA2 and HERC2

If we’re being honest, most of the heavy lifting is done by two genes located close to each other on chromosome 15. These are the "celebrities" of the eye color genetic chart.

The OCA2 gene produces a protein called P protein, which is involved in the maturation of melanosomes. Melanosomes are cellular structures that produce and store melanin. If you have a lot of melanin in your iris, you have brown eyes. Very little? You get blue.

Then there’s HERC2. Think of HERC2 as the master switch for OCA2. A specific mutation in HERC2 can basically "turn off" the OCA2 gene, leading to a lack of pigment. This is why scientists like Dr. Hans Eiberg from the University of Copenhagen have famously suggested that every blue-eyed person on Earth shares a single common ancestor who lived 6,000 to 10,000 years ago. Before that mutation, everyone had brown eyes. Period.

It’s wild to think about.

But even with OCA2 and HERC2, things get messy. There are other genes like ASIP, IRF4, SLC24A4, and TYR that act as modifiers. They can tweak the amount of pigment or how light scatters within the eye, giving us those "in-between" colors like green, amber, or grey.

Why the Simple Charts Fail

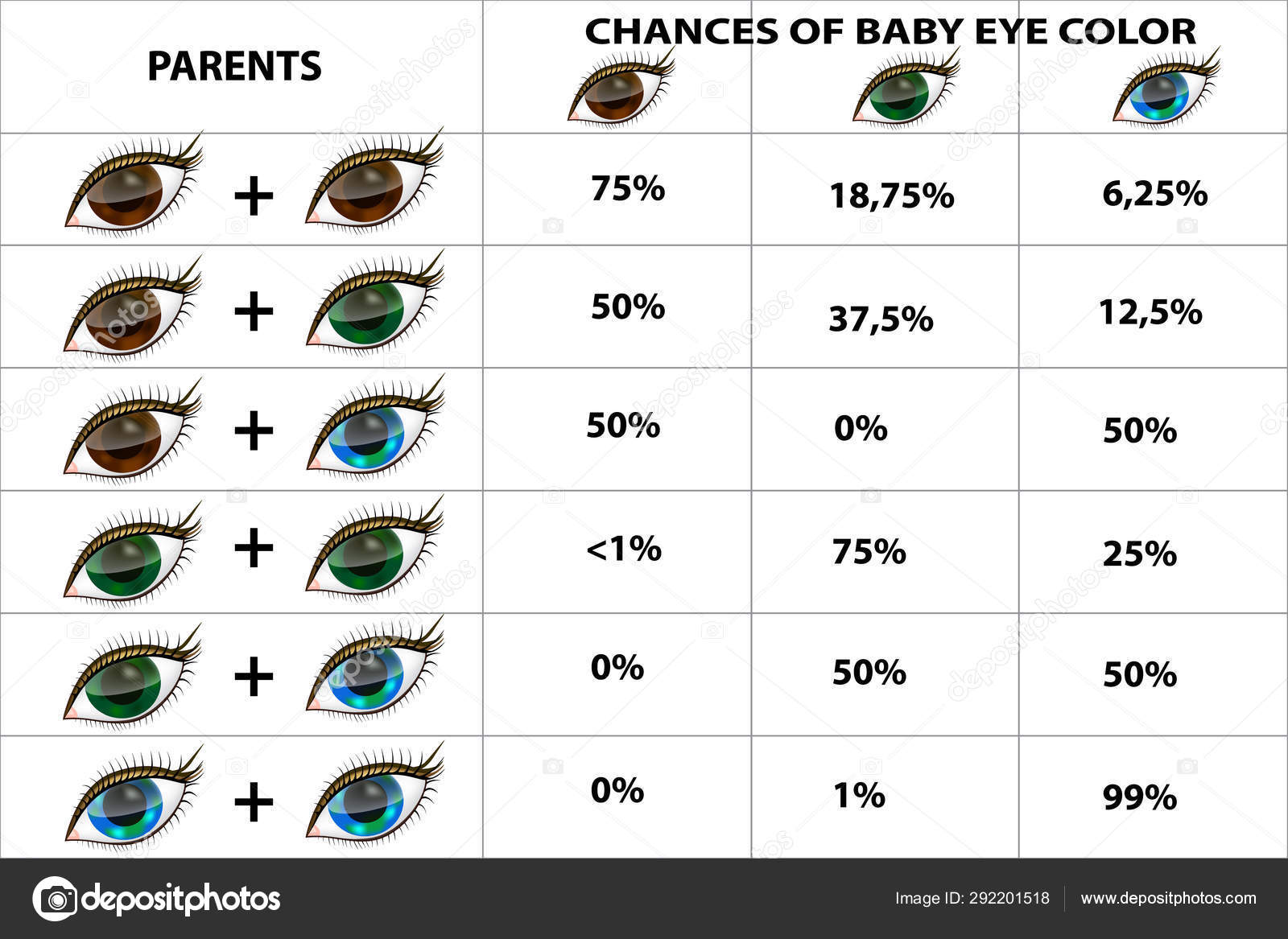

Most people go to a "calculator" or a basic eye color genetic chart and see something like this:

- Brown + Brown = 75% Brown, 18% Green, 6% Blue

- Blue + Blue = 99% Blue, 1% Brown

While these percentages are okay for a rough guess, they don’t account for the "genetic outliers." Have you ever seen two blue-eyed parents have a brown-eyed child? According to the old-school rules, that’s impossible. But it happens.

It happens because of "epistasis." This is where one gene masks or interferes with the expression of another. If a parent carries a "hidden" dominant brown gene that was suppressed by another genetic factor, they can pass that brown gene to their child. Suddenly, the "impossible" happens.

Also, look at green eyes. Green isn't actually a pigment. There is no "green" chemical in the eye. Green eyes are the result of a low level of brown melanin combined with something called Rayleigh scattering. This is the same phenomenon that makes the sky look blue. Light hits the iris, scatters, and when it mixes with a tiny bit of yellowish pigment (lipochrome), it looks green to the human eye.

The Mystery of Changing Eye Color

Babies are the ultimate example of why a static eye color genetic chart is just a snapshot, not a final verdict.

Most Caucasian babies are born with blue or grey eyes. This isn’t because they have "blue genes"—it’s because the melanocytes (pigment-producing cells) haven't been fully activated by light yet. It’s like a Polaroid photo that hasn't finished developing. Over the first three years of life, melanin builds up. A baby born with slate-grey eyes might end up with dark chocolate brown eyes by their third birthday.

🔗 Read more: Maine General Neurology Augusta Maine: What You Should Actually Expect

In some rare cases, eye color can even change in adulthood. This usually isn't a genetic shift but rather a physical one. Fuch’s heterochromic iridocyclitis or pigmentary glaucoma can change the appearance of the iris. If your eye color changes suddenly as an adult, don't check a chart—see an ophthalmologist.

Heterochromia and Other Oddities

Sometimes the body just decides to get creative. Heterochromia is when a person has two different colored eyes or multiple colors within the same eye.

- Complete Heterochromia: Think Max Scherzer or Kate Bosworth. One eye is totally blue, the other is brown or green.

- Sectoral Heterochromia: A "splash" of a different color in one iris.

- Central Heterochromia: A different colored ring around the pupil. This is actually super common and is often what people are seeing when they claim their eyes "change color" based on their clothes.

Genetically, this can be caused by mosaicism (where different cells have different genetic makeups) or simple trauma during development. It’s a reminder that DNA isn't a rigid blueprint; it’s more like a live performance where the actors sometimes ad-lib.

What About "Rare" Colors?

You’ll often hear people claim that "purple" or "red" eyes exist. Technically, in cases of severe albinism, the lack of melanin is so complete that the blood vessels at the back of the eye show through. This creates a reddish or violet hue.

But for the general population?

Green is widely considered the rarest "standard" color, found in only about 2% of the world.

Grey is also exceptionally rare and is often mistaken for blue, though grey eyes tend to have more collagen in the stroma, which changes how light reflects.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you're staring at your partner and trying to figure out if your kid will have your "ocean eyes," remember that you are carrying a library of genetic history you can't see. You might have brown eyes but carry the "blue" switch from a grandparent.

The most accurate way to look at an eye color genetic chart is to view it as a map of probabilities, not a contract.

- Look at the grandparents. This gives you a better idea of the "hidden" alleles you might be carrying.

- Understand the "Brown Dominance" rule. Generally, darker pigment is more likely to express because it requires fewer specific "off" switches.

- Prepare for the three-year wait. Don't paint the nursery to match the newborn's eyes. They will likely change.

- Value the modifiers. Hazel, amber, and grey eyes are the results of subtle genetic "volume knobs" being turned up or down.

Ultimately, your eye color is a unique signature of your ancestry. It tells a story of migrations, mutations, and the weird, wonderful way light interacts with matter. While a chart can give you a hint, the real magic happens in the unpredictable shuffle of DNA.

If you're curious about your own specific genetic makeup, modern DNA testing kits (like 23andMe or AncestryDNA) can actually look at your specific SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) on the OCA2 and HERC2 genes. They can tell you if you’re a "carrier" for certain colors. It’s much more precise than a paper chart, though even then, they’ll give you a "likelihood" rather than a 100% guarantee.

Science is still uncovering new genes that influence the subtle rings and patterns in the iris. We might never have a "perfect" chart, and honestly, that’s part of the beauty.

Practical Next Steps for Curious Parents or Students

- Audit your family tree: Track the eye colors of your parents and grandparents. If you see a lot of blue or green in the past, your chances of carrying those "recessive" traits are significantly higher, even if you have dark brown eyes.

- Use a digital simulator: Seek out polygenic eye color calculators online that allow you to input the phenotypes of multiple generations rather than just the parents.

- Consult a genetic counselor: If you are genuinely concerned about eye-color-related conditions (like ocular albinism), a professional can provide a medical-grade analysis of your genetic risks.

- Observe iris patterns: Take a high-resolution photo of your eye in natural light. Look for "crypts" (small pits) or "furrows." These physical traits are also hereditary and can be just as interesting as the color itself.