You’ve been lied to. Or, at the very least, your third-grade geography teacher unintentionally misled you with that giant, glossy poster pinned above the chalkboard.

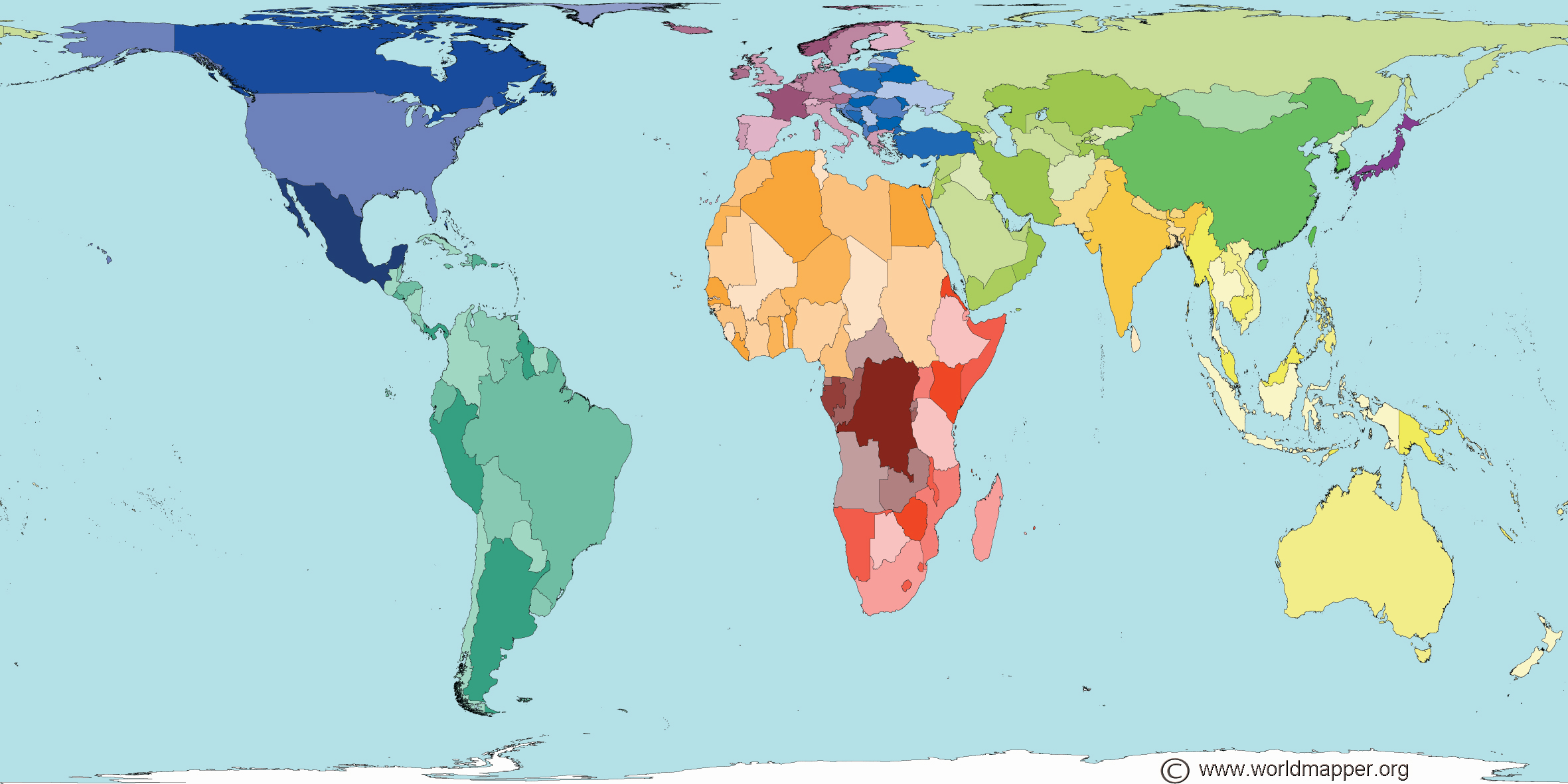

Most people grow up thinking Greenland is roughly the size of Africa. It looks like it on a standard classroom map, right? In reality, Africa is about 14 times larger than Greenland. You could fit Greenland, the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa’s borders and still have room for a coffee break. The reason for this massive visual error is a mathematical headache that has plagued cartographers for centuries: you simply cannot create a map of world to scale on a flat piece of paper.

Mathematics is stubborn. If you try to flatten a sphere—like our Earth—onto a 2D surface, something has to give. Think of it like trying to gift-wrap a bowling ball without wrinkling the paper. You can’t do it. You either have to tear the paper or stretch it. In the world of map-making, those "stretches" are called distortions. They change the shape, the area, the distance, or the direction of landmasses.

🔗 Read more: The English to Aramaic Translator Google Search Won't Find

The Mercator Problem and Why Your Eyes Deceive You

Gerardus Mercator changed everything in 1569. He designed a map that was a godsend for sailors. If you drew a straight line between two points on his map, that line represented a constant compass bearing. For a 16th-century navigator tossing around in the Atlantic, that was literally a lifesaver.

But there’s a catch. A huge one.

To keep those lines straight for navigation, Mercator had to stretch the map toward the poles. This creates what we call "area distortion." The further a country is from the equator, the more bloated it looks. That’s why Europe looks massive and South America looks relatively small, even though South America is nearly twice the size of Europe.

Honestly, it’s kind of a mess.

We’ve become so used to this specific distortion that it shapes our geopolitical worldview. We perceive northern nations as "bigger" and therefore more dominant, while tropical regions near the equator are visually shrunken. It’s a tech-driven bias that has persisted for over 450 years.

Comparing the Contenders: Gall-Peters vs. Robinson

Because the Mercator projection is so skewed, other geographers tried to fix it. Enter the Gall-Peters projection. This is an "equal-area" map. It shows the relative sizes of countries accurately.

✨ Don't miss: Why Social Media Shouldn't Fact Check: What Most People Get Wrong About Online Speech

If you look at a Gall-Peters map of world to scale in terms of area, the world looks... weird. The continents look stretched vertically, like they’ve been pulled through a pasta maker. Africa looks like a long, hanging teardrop. While it’s more "fair" in terms of size, it’s terrible for shape. Brazil looks like it’s melting.

Then you have the Robinson projection. This was the "let's just compromise" map. National Geographic used it for years. It doesn’t get the area perfectly right, and it doesn't get the shapes perfectly right either. It just tries to make everything look "natural" to the human eye. It rounds the edges of the world. It’s a visual vibe rather than a mathematical truth.

The True Size of Our World

If you want to see how much you’ve been fooled, check out "The True Size Of" website. It’s a digital tool that lets you drag countries around a Mercator map.

- Drag the Democratic Republic of Congo up to Europe; it covers nearly the entire continent.

- Move the UK down to the equator; it becomes a tiny speck.

- Slide Antarctica to the equator; it turns from a world-swallowing white blob into a modest-sized island.

It’s jarring. Our brains are hardwired to trust what we see on the page, but when it comes to a map of world to scale, the page is always lying to you.

The Digital Solution: Are Globes the Only Answer?

In 2026, we have tools that 16th-century cartographers would kill for. We have Google Earth. We have real-time satellite imagery.

Digital globes solve the scale problem by staying in 3D. When you zoom out on a digital sphere, you are seeing the world as it actually exists in space. There is no distortion because there is no flattening. However, the moment you try to print that digital globe onto a phone screen or a poster, the math kicks back in. You’re back to making choices about what to distort.

📖 Related: DIRECTV Kids on iPad on YouTube: How to Actually Stream Without the Headache

Even modern GPS apps use a variation of Mercator (Web Mercator) because, for a person walking down a street, keeping the angles of street corners correct is more important than knowing if their city is visually shrunken compared to Greenland.

The AuthaGraph: The Closest We’ve Ever Gotten

In 2016, a Japanese architect named Hajime Narukawa created something called the AuthaGraphic World Map. It’s probably the most accurate map of world to scale ever made that can still be flattened.

He did this by dividing the globe into 96 triangles, projecting them onto a tetrahedron (a pyramid shape), and then unfolding that pyramid. It maintains the proportions of land and water much better than any other projection. It’s messy to look at because the North Pole isn't necessarily at the "top" in the way we expect, but it’s mathematically superior.

It reminds us that "up" is an arbitrary concept in space. We put North at the top because of historical European power, not because the universe has a ceiling.

Actionable Ways to See the World Accurately

Stop relying on the wall map in your office. If you want to actually understand how big the world is, you need to change your perspective.

- Use a physical globe. It is the only way to see the true distance between points like Anchorage and Moscow.

- Toggle your map settings. In Google Maps (desktop), zoom out until the map turns into a globe. This removes the Mercator distortion that occurs at high zoom levels.

- Compare by area, not by sight. Always look up the square mileage if you are comparing two regions for business or travel planning.

- Study the Dymaxion Map. Created by Buckminster Fuller, this map shows the world as one continuous island in one ocean. It’s great for understanding human migration patterns.

The reality is that every flat map is a trade-off. You trade truth for convenience. You trade size for direction. You trade beauty for accuracy. To truly see a map of world to scale, you have to stop looking at the paper and start looking at the math.

The next time you look at a map, look at the equator. Everything there is closer to the truth. The further your eyes wander North or South, the more you're looking at a mathematical fiction. Recognize that "big" on a map often just means "far from the center." Adjust your perspective accordingly.