You remember the plastic yellow blocks from second grade. The cube. The pyramid. Maybe that weird translucent sphere that rolled off your desk and into the radiator. Back then, it was all about naming them. But if you actually sit down and look at how 3D shapes and vertices function in the real world—specifically in the code that runs your favorite video games or the structural engineering behind a skyscraper—the math gets a lot more interesting and, honestly, a little messier than those elementary school worksheets suggested.

Geometry isn't just a collection of static objects. It is the language of space.

What a Vertex Actually Is (And Why It Isn't Just a Corner)

We usually define a vertex as a "corner." That’s fine for a seven-year-old. But if you’re trying to understand the geometry of our universe, a vertex is a precise coordinate in a multidimensional system. It is the zero-dimensional point where edges meet. Think of it as a spatial anchor. Without the vertex, there is no shape; there is only infinite, directionless potential.

In a standard Euclidean cube, you have eight of these anchors. They aren't just decorative. In 3D modeling software like Blender or Autodesk Maya, these vertices are the only things the computer truly "sees." The flat faces and the straight lines (edges) are just instructions telling the computer how to connect those dots. If you move one vertex, the whole reality of the shape warps. It’s a ripple effect.

The Euler Characteristic: The Math That Shouldn't Work (But Does)

Leonhard Euler was a 18th-century Swiss mathematician who basically looked at a pile of shapes and realized something spooky. He found a consistency that applies to a massive variety of polyhedra. It’s called the Euler Characteristic.

The formula is $V - E + F = 2$.

📖 Related: 20 Divided by 21: Why This Decimal Is Weirder Than You Think

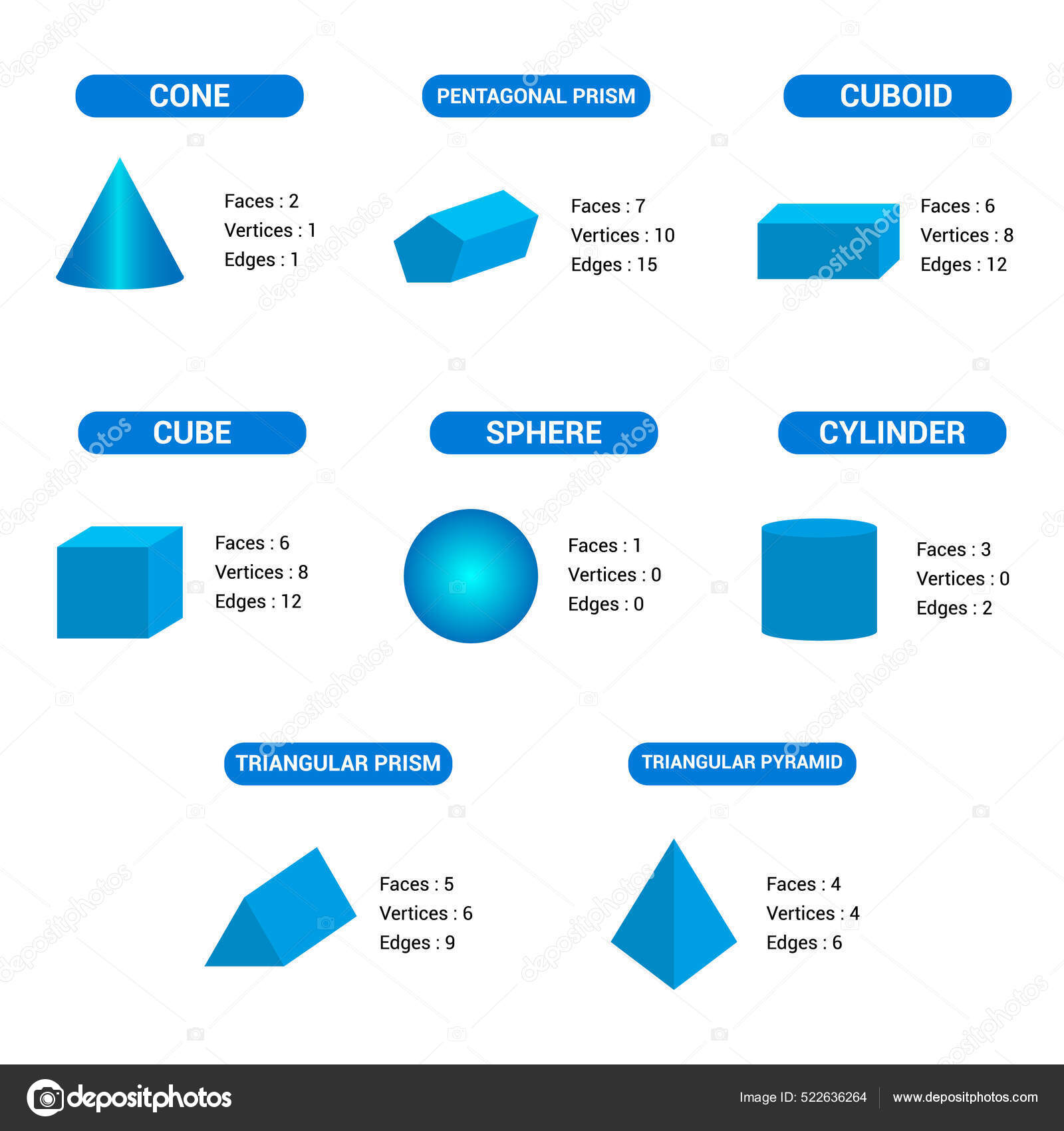

That stands for Vertices minus Edges plus Faces equals two. Try it on a cube. You have 8 vertices. Subtract 12 edges (8 - 12 = -4). Add 6 faces (-4 + 6 = 2). It works. It works for a triangular pyramid. It works for a complex dodecahedron. It’s one of those rare moments where the universe seems to have a built-in cheat code. However, there is a catch. This only applies to "convex" polyhedra. If you have a shape with a hole through the middle—like a 3D donut (a torus)—the math breaks. For a torus, $V - E + F = 0$. This branch of math is called topology, and it’s why mathematicians famously joke that they can’t tell the difference between a coffee mug and a donut. They both have one hole.

The Problem With Spheres

Here is a fun fact that ruins the "corner" definition: a sphere has no vertices.

It also has no edges.

Strictly speaking, a sphere is a single, continuous face. In the world of 3D shapes and vertices, the sphere is the ultimate outlier. Because it lacks these "anchors," representing a sphere in digital space is actually impossible. If you zoom in far enough on a "sphere" in a video game, you’ll see it’s actually made of thousands of tiny flat triangles. This is called tessellation. To make a round object look round, we have to fake it by cramming so many vertices together that the human eye just gives up and sees a curve.

Platonic Solids and the Perfection Myth

Plato, the Greek philosopher, was obsessed with these things. He thought the entire universe was built out of five specific shapes because they were "perfect." To be a Platonic solid, every face must be the exact same regular polygon, and the same number of faces must meet at every vertex.

👉 See also: When Can I Pre Order iPhone 16 Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

There are only five:

- The Tetrahedron (4 faces)

- The Cube (6 faces)

- The Octahedron (8 faces)

- The Dodecahedron (12 faces)

- The Icosahedron (20 faces)

People used to think these shapes represented the elements—earth, air, fire, water, and the "aether." While that’s obviously scientifically bunk, these shapes do show up in nature constantly. Look at a grain of salt under a microscope. It’s a cube. Look at the structure of certain viruses, like the herpes simplex virus. It’s an icosahedron. Nature loves these shapes because they are the most efficient way to distribute energy and structural stress across a set of vertices.

Architecture and the Strength of the Vertex

Why are most houses built with rectangular frames but most massive domes built with triangles? It comes down to how 3D shapes and vertices handle pressure.

A rectangle is unstable. If you push on the side of a wooden square frame, it collapses into a parallelogram. The vertices have too much "wiggle room." But a triangle? A triangle is rigid. If you have three edges meeting at three vertices, you cannot change the angles without physically breaking the material. This is why the "Geodesic Dome," popularized by Buckminster Fuller, is so revolutionary. By creating a sphere-like structure out of a massive network of triangles, you create a building where the stress is distributed perfectly across every single vertex. You can build them incredibly thin and they’ll still support massive weight.

High-Dimensional Vertices: Thinking Outside the 3D Box

We live in three dimensions, but math doesn't have to. We can mathematically calculate the vertices of a Tesseract—a 4D hypercube. A 3D cube has 8 vertices. A 4D hypercube has 16.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your 3-in-1 Wireless Charging Station Probably Isn't Reaching Its Full Potential

It sounds like sci-fi, but this is how data science works. When companies like Netflix or Amazon suggest a movie or a product to you, they are essentially placing "you" as a vertex in a multi-dimensional space. They might use 500 different dimensions (age, location, past purchases, etc.) to define your "shape." The closer your vertex is to a movie's vertex in that 500-dimensional space, the more likely you are to see it in your "Recommended for You" section. Geometry isn't just about blocks; it's about relationships between points.

Common Misconceptions You Probably Have

Most people think "3D" means "solid." It doesn't. In geometry, we often talk about the surface of the shape. A cube isn't the wood inside the block; it's the boundary where the block ends and the air begins.

Another weird one: the Cylinder. Does a cylinder have vertices? If you go by the "intersection of three or more edges" rule, then no. A cylinder has two circular edges and one curved surface. No corners. Same for a cone, though a cone has an "apex." Is an apex a vertex? Technically, yes, but it’s a singular point where the surface folds back on itself. It’s a lonely vertex.

Actionable Insights: Using This Knowledge

If you’re a hobbyist, a student, or just someone who likes knowing how things work, here is how you can apply this:

- Digital Art and Design: If you are learning 3D modeling, focus on "topology." Good topology means placing your vertices in a way that allows the shape to deform without stretching. Avoid "N-gons" (faces with more than four vertices) because they render poorly.

- DIY Construction: If you are building a deck or a shed, always use cross-bracing to create triangles. You are essentially adding a vertex and an edge to turn a wobbly square into two rigid triangles.

- Data Visualization: When looking at complex charts, remember that every data point is just a vertex in a conceptual shape. Change the vertex, and you change the story the data tells.

The next time you look at a building or play a game, try to see the wireframe. See the points in space that hold the whole thing together. Once you start noticing 3D shapes and vertices, you realize that the world isn't made of "stuff"—it's made of coordinates.

To deepen your understanding, try downloading a free program like Blender. Create a simple cube and start moving individual vertices. You will quickly see how the relationship between those points dictates every single object in our physical and digital reality. Understanding the skeleton of the world is the first step to building something new within it.