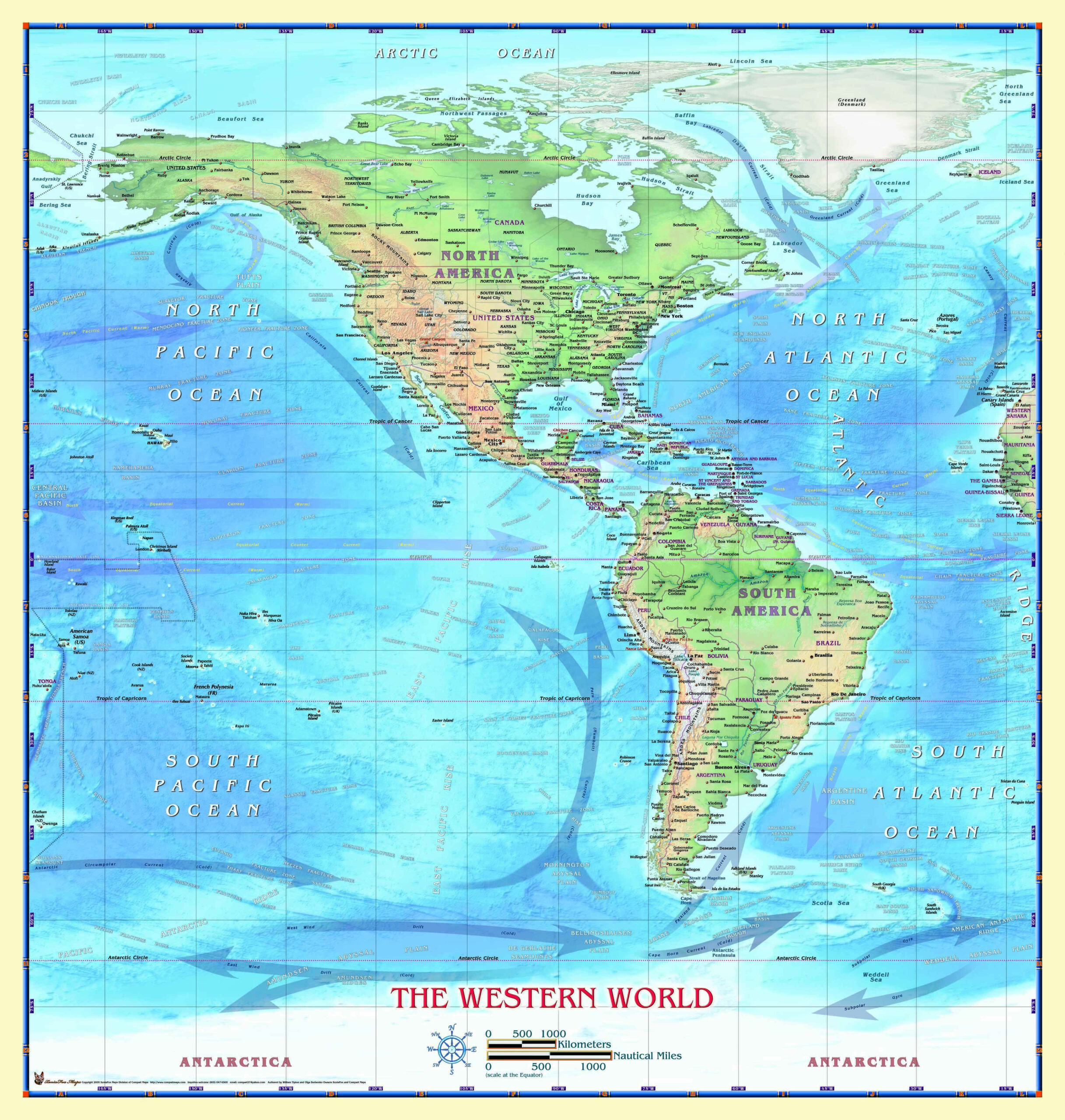

Map reading is a lost art. Honestly, most people just pinch and zoom on a smartphone screen until a blue dot tells them where to stand, but that doesn't help you understand the literal half of the planet we live on. When you look at a labeled map of western hemisphere, you aren't just looking at a drawing of landmasses. You’re looking at a specific geopolitical and cartographic slice of Earth that contains about 2 billion people and some of the most intense geographical diversity ever recorded.

It’s huge.

The Western Hemisphere technically starts at the Prime Meridian (0° longitude) and ends at the 180th meridian. This includes all of North and South America, a chunk of western Europe, a slice of Africa, and a massive portion of Antarctica. Most people just think "The Americas," but cartography is messier than that. If you're using a labeled map of western hemisphere for navigation or study, you've probably noticed that where the labels go—and what they prioritize—changes depending on who made the map.

✨ Don't miss: Why Halloween Costumes With Pigtails Are Actually The Easiest Way To Win October

The Weird Geography of the "Left" Side of the World

Ever wondered why the Atlantic Ocean looks so massive on some maps and like a narrow strip on others? It’s the projection. Most labeled maps you'll find online use the Mercator projection, which makes Greenland look like it’s the size of Africa. It isn't. Not even close. Africa is actually fourteen times larger than Greenland. This distortion matters because when you label a map, the text for "Greenland" ends up being as large as the text for "South America," giving students a totally warped sense of reality.

We have to talk about the "Four Hemispheres" problem. Earth is a sphere, so you can divide it any way you want. But the Western Hemisphere is defined by the Prime Meridian in Greenwich, London. This means a tiny bit of the United Kingdom, France, and Spain actually sit in the Western Hemisphere. If your labeled map doesn't show the edge of the Ivory Coast or the tip of Morocco, it’s technically incomplete.

Cartographers like Dr. Edward Said have historically pointed out how these maps shape our "imaginative geography." We tend to group everything in the West as a single cultural unit, but a labeled map shows the absurdity of that. You have the Arctic tundra of Nunavut, Canada, and the tropical rainforests of the Amazon, all sharing the same longitudinal slice.

The Major Labels You Can't Miss

If you're looking at a standard labeled map of western hemisphere, the big hitters are obvious: North America and South America. But the labels in between—Central America and the Caribbean—are where things get crowded.

- North America: Includes Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Greenland is geographically part of North America but politically tied to Denmark (Europe).

- South America: Twelve sovereign states and two dependent territories. Brazil is the giant here, taking up nearly half the landmass.

- Central America: That narrow bridge. It’s an isthmus. Specifically, the Isthmus of Panama is the literal "knot" holding the two continents together.

- The Caribbean: This is a nightmare for map labelers. You’ve got the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico) and the Lesser Antilles. Try fitting "Saint Vincent and the Grenadines" on a map the size of a postcard. It doesn't work well.

Why Longitude Dictates Your Life

The Western Hemisphere isn't just about land; it's about time. Because this hemisphere covers 180 degrees of longitude, it encompasses roughly half the world's time zones. When you look at a map labeled with time zones, you see the "zigzag" lines. These aren't straight because humans are complicated. Kiribati, for example, shifted the International Date Line in the 1990s just so the whole country could be on the same day at the same time.

Politics always wins over math.

Most maps of the Western Hemisphere will focus on the UTC-5 to UTC-8 range (Eastern Standard Time to Pacific Standard Time). But go further east to the Azores or further west to the Aleutian Islands, and the labels start to shift into territory that feels like the "edge" of the world.

Common Misconceptions About the Western Hemisphere

Most people get the "Middle East" confused with geography when it's actually a geopolitical term. Similarly, "Latin America" is often confused with the Western Hemisphere. They aren't the same. Latin America is a cultural and linguistic label. The Western Hemisphere is a hard geographic boundary.

- Is Hawaii in the Western Hemisphere? Yes. It’s around 155° West.

- Is New Zealand in it? No. It sits around 174° East, making it part of the Eastern Hemisphere.

- What about the Aleutian Islands? This is the ultimate trivia question. Some of the Aleutian Islands actually cross the 180th meridian, meaning part of Alaska (and therefore the US) is technically in the Eastern Hemisphere.

If your labeled map doesn't show that little "jog" in the line near Alaska, it's a simplified version. Professionals use the "International Date Line" as a functional boundary, but the 180th meridian is the actual geographic one.

The Role of Oceans in Mapping

A good labeled map of western hemisphere won't just name the countries. It has to name the water. You have the Pacific to the west and the Atlantic to the east. But the labels for the "Southern Ocean" (around Antarctica) and the "Arctic Ocean" are just as vital.

The Gulf of Mexico and the Hudson Bay are two massive bodies of water that define the climate for millions. Without the Gulf Stream—that warm current starting in the Gulf—Europe would be a frozen wasteland. The map shows the "where," but the currents tell the "why."

Digital vs. Paper Maps

Kinda weird to think about, but a paper map is static. It's a snapshot in time. Borders change. In the last 30 years, we’ve seen names change (like the shift from "Mount McKinley" to "Denali" on Alaskan maps). Digital maps like Google Earth or MapBox allow for "layers." You can toggle labels for topographic features, city populations, or even real-time weather.

But there’s something about a high-quality, printed labeled map. It forces you to see the spatial relationship between Bogota and Miami that a small screen hides. Did you know Bogota, Colombia, is actually further east than Miami, Florida? Most people would bet money it’s the other way around. Look at a labeled map; it'll prove you wrong.

How to Use This Knowledge

If you’re a student, a traveler, or just someone who likes knowing where things are, stop relying on GPS for the "big picture." GPS is great for finding a Starbucks. It’s terrible for understanding why the Panama Canal was built where it was.

Actionable Insights for Map Enthusiasts:

- Check the Projection: If you’re buying a wall map, look for a "Robinson" or "Winkel Tripel" projection. These minimize the distortion of land sizes so Brazil doesn't look smaller than Alaska (it’s actually much larger).

- Identify the "Dead Zones": Look at the labels for the Amazon Basin or the Canadian Shield. Notice the lack of cities. These are "geographic barriers" that have dictated human history for centuries.

- Trace the 100th Meridian: In the United States, this is the "dry line." To the east, it’s humid and green; to the west, it’s arid. A good labeled map often shows this transition in vegetation color.

- Verify Your Labels: Ensure your map includes the "Overseas Departments" like French Guiana. It’s a part of France (and the EU) located right on the north coast of South America. If it’s not labeled, the map is skipping the details.

Understanding the Western Hemisphere isn't just about memorizing capitals. It's about seeing the physical layout of the world and realizing how much the "where" affects the "how" of our lives. From the mountain peaks of the Andes to the sprawling Great Plains, the labels on the map are just the beginning of the story.

Go find a physical map. Trace the coastline with your finger. You'll notice things a screen will never show you. Geography is a physical reality, not just a digital data point. Knowing where you are in the hemisphere changes how you see your place in the world.