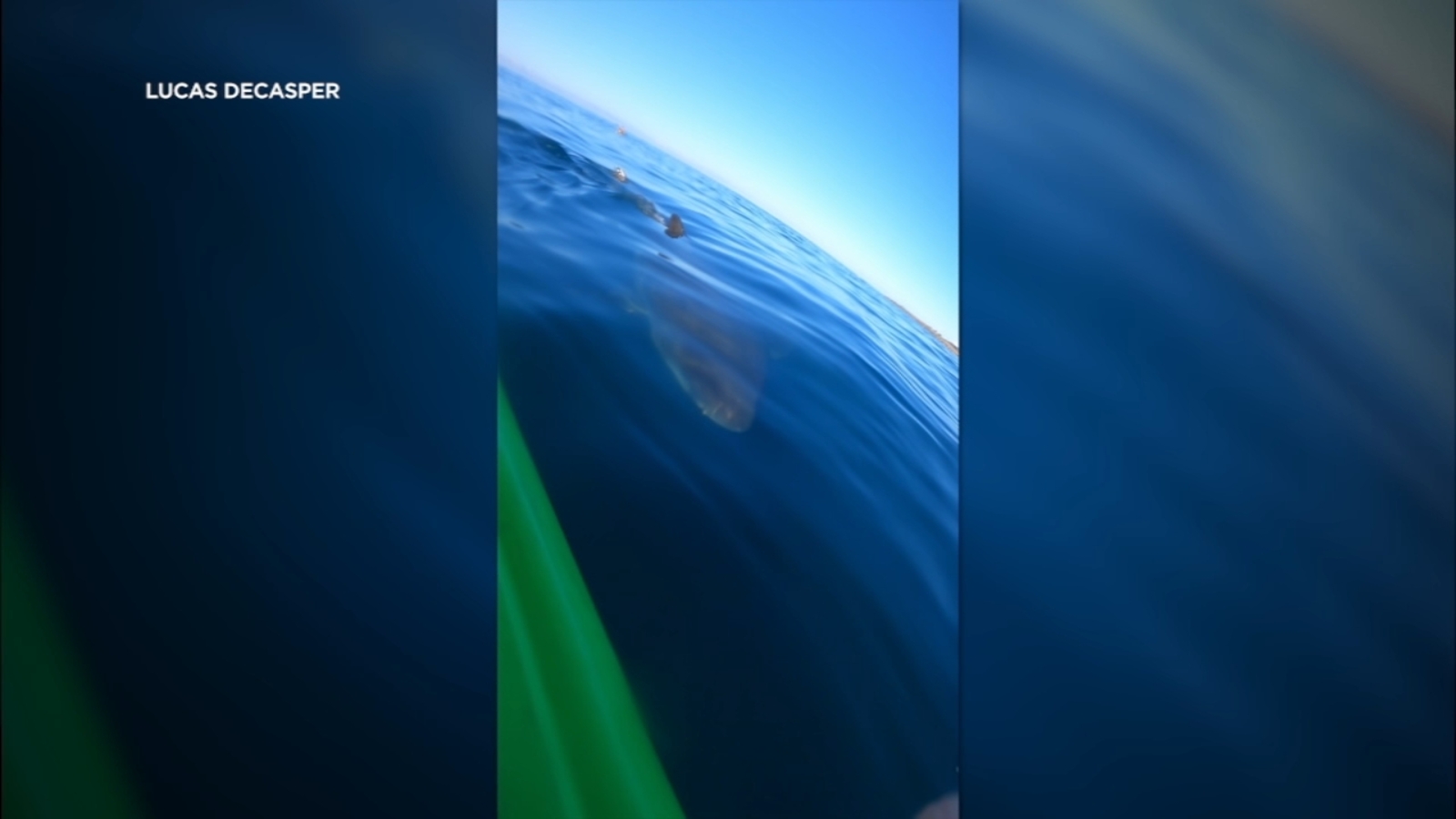

You’ve seen the footage. It’s usually grainy, shot on a vibrating GoPro, and features a rhythmic slap-slap-slap of a plastic paddle against the Pacific. Then, the shadow appears. It’s a dark, torpedo-shaped silhouette that makes the 12-foot kayak look like a toothpick. When a great white follows kayak enthusiasts, the internet loses its mind, but the reality for the person in the seat is a weird mix of adrenaline and total, paralyzing stillness.

It’s not just a movie trope.

Most people think these encounters are "attacks" in the making. They aren't. If a 2,000-pound Carcharodon carcharias wanted to eat a kayaker, the video would be over in four seconds. Instead, these interactions often last for twenty minutes or more. The shark just hangs there. It lingers. It drifts five feet behind the stern, matching the kayaker's pace with terrifying precision. Why? Because you’re the most interesting thing that’s happened to that shark all day.

The Science of Curiosity vs. Predation

Great whites are essentially toddlers with chainsaws for teeth. They are incredibly tactile. Since they don't have hands, they use their mouths and their electro-reception to understand the world. When a great white follows kayak setups, it’s usually performing what biologists call "investigatory behavior."

Dr. Chris Lowe from the CSU Long Beach Shark Lab has spent years tracking these animals. His research shows that juvenile and sub-adult great whites often frequent "nurseries" in shallow water—exactly where people like to paddle. These sharks are often just as nervous as the humans are. They’re checking out the vibration of your hull. Your paddle strokes create low-frequency pressure waves that mimic a wounded fish, but once the shark gets close, it realizes you don't smell like a seal. You smell like polyethylene and sunscreen.

The shark stays because it’s trying to solve a puzzle. You’re a large, floating object that doesn’t behave like a prey item. You aren't darting away in a panic. You’re just... there.

📖 Related: Creative and Meaningful Will You Be My Maid of Honour Ideas That Actually Feel Personal

Real-World Encounters: The Cape Cod and California Hotspots

Take the 2023 encounter off the coast of Santa Cruz. A kayaker named Brian Correiar was literally knocked out of his boat by a great white. That’s a "follow" gone wrong. But more often, you get the experience of someone like David Shull, who filmed a large white shark trailing him for over half a mile in Southern California.

In Shull’s footage, you can see the shark’s dorsal fin break the surface. It’s calm. There’s no splashing. This is a predatory animal in "energy conservation mode."

- The "Shadowing" Phase: The shark stays 10–15 feet back.

- The "Close Approach": It might swim directly under the kayak to see the shape against the sun.

- The "Break Away": Usually, the shark loses interest and vanishes into the blue.

It’s worth noting that in places like Cape Cod, the dynamic is different. There, the water is murkier. Gray seals are everywhere. When a great white follows kayak users in the Atlantic, the risk of a "mistaken identity" bite is statistically higher because the shark has less time to visually confirm what you are before deciding to taste-test.

What Most People Get Wrong About Shark Following

Honestly, the biggest misconception is that the shark is "stalking" you like a slasher villain.

If a shark is following you, it’s actually a good sign. It means it hasn't decided to strike. Ambush predators like the great white rely on the element of surprise. They hit from below, at high speeds, often launching their entire bodies out of the water (breaching). If you can see the shark following you, you are likely not in the middle of a predatory strike. You’re in a negotiation.

👉 See also: Cracker Barrel Old Country Store Waldorf: What Most People Get Wrong About This Local Staple

Sharks have "Ampullae of Lorenzini." These are tiny pores on their snout that detect electrical fields. Your heartbeat, the friction of your boat against the water, and even the metal components in your fishing gear all scream "Look at me!" to a shark. It’s basically an irresistible curiosity lure.

Survival Tactics: If You Realize You’re Being Followed

Don't scream. Seriously. High-pitched noises and frantic splashing are the universal language for "I am a dying animal, please eat me."

If you find that a great white follows kayak path you’ve set, you need to become the most boring thing in the ocean.

- Stop Paddling. Or, at least, minimize the splash. Smooth, deep strokes are better than short, choppy ones.

- Keep Your Eyes on the Shark. Predators hate being watched. It’s why many divers wear masks with eyes painted on the back. If the shark knows you see it, you aren't an easy target.

- Maintain Your Position. Don't try to outrun it. You can't. A great white can hit 35 mph. You can hit... four? Maybe five? You win by being a sturdy, uninteresting object, not a fleeing prey animal.

- Paddle Toward Shore (Slowly). Keep a steady rhythm. Avoid the "surf zone" where sharks are used to seeing seals play.

The Psychological Toll of the "Follow"

Let’s be real: your heart is going to be hitting 180 beats per minute. The "thump" of a shark’s tail hitting the side of a plastic kayak is a sound you never forget. It sounds like a muffled bass drum.

Kayakers often report a "post-encounter high." It’s a mix of terror and a profound realization that we aren't at the top of the food chain once we leave the sand. But the data doesn't lie. Despite the thousands of people who kayak in shark-heavy waters every year, the number of actual bites is incredibly low. You are more likely to die from a falling vending machine or a lightning strike while putting your kayak on the roof rack.

✨ Don't miss: Converting 50 Degrees Fahrenheit to Celsius: Why This Number Matters More Than You Think

Actionable Steps for Your Next Paddle

If you’re heading out into known white shark territory—like the "Red Triangle" in Northern California or the waters off Gansbaai—prepare your gear and your mindset.

Check the Water Temp

Great whites love the "Goldilocks" zone. They prefer water between 54°F and 75°F ($12°C$ to $24°C$). If you’re in that range, you’re in their living room.

Avoid Seal Colonies

This seems obvious, but people forget. If you see a rock covered in barking seals, do not paddle near it. You are literally entering the "attack zone." The shark isn't following you because it likes you; it’s following you because you’re hanging out in its dining room.

Gear Up with Electronic Deterrents

Devices like the Sharkbanz or Shark Shield use powerful electromagnetic fields to overwhelm a shark’s sensitive snout. It’s like a "bad smell" for their electrical sense. It’s not 100% foolproof, but it’s a significant layer of protection if a great white follows kayak for too long.

Watch the Birds

If you see birds diving or "boiling" water, there’s baitfish. Where there’s baitfish, there are bigger fish. Where there are bigger fish, there’s usually a great white. Stay clear of active feeding frenzies.

The Buddy System is Non-Negotiable

A shark is far less likely to approach two kayaks than one. If you are followed, pull your kayaks together. Creating a larger "profile" makes you look like a massive, confusing organism that isn't worth the risk of an attack.

Ultimately, seeing a great white from a kayak is a rare privilege, even if it feels like a nightmare in the moment. You’re witnessing one of the world's last great apex predators in its natural element. Stay calm, keep your paddle low, and enjoy the story you’ll be telling for the rest of your life.