If you pick up a copy of Jules Verne’s masterpiece today, you might expect a dusty, slow-moving relic of Victorian literature. You’d be wrong. Honestly, the most shocking thing about 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea isn't the giant squid or the underwater hunting trips; it’s how much Verne actually got right about the future of technology and human isolation.

He wrote this in 1870.

Think about that for a second. While the world was still figuring out basic electricity and steam engines were the peak of sophistication, Verne was dreaming up a self-sustaining, electric-powered "submarine boat" that could cruise the ocean floor indefinitely. It wasn't just a fantasy; it was a blueprint. People often confuse the "leagues" in the title with depth. They think Pierre Aronnax and Captain Nemo were literally four miles straight down. They weren't. A league is a unit of distance, roughly three miles. The "20,000" refers to the distance traveled horizontally while submerged. If they had gone 20,000 leagues deep, they’d have come out the other side of the planet and kept going into space.

The Real Genius Behind the Nautilus

Captain Nemo is basically the original anti-hero. He's brilliant, wealthy, and deeply traumatized by the colonial politics of the surface world. When we first meet the Nautilus through the eyes of Professor Aronnax, it’s described as a "long, spindle-shaped object" that the world thinks is a giant narwhal. It's funny how history repeats itself; today we have "UAPs" and "unidentified submerged objects" that baffle the Navy, and back in the 1860s, Verne was playing with that exact same sense of maritime dread.

The Nautilus wasn't magic. Verne spent pages—sometimes too many pages, if we're being real—explaining the mechanics. He utilized the "sodium battery" concept. He understood that the ocean was a massive reservoir of energy. While his contemporaries were burning coal and choking on smog, Nemo was harvesting the sea. This reflects a level of ecological foresight that feels incredibly modern. Nemo views the surface world as a place of tyranny and the ocean as the only place where a man can be truly free. "The sea does not belong to despots," he famously says. It’s a sentiment that resonates with anyone who’s ever wanted to just delete their social media and disappear into the wild.

Why We Keep Coming Back to the Abyss

There is something inherently terrifying about the deep ocean. Even now, we’ve mapped more of the moon’s surface than we have the seafloor. Verne tapped into that "sublime" fear—the mixture of awe and absolute terror. The famous battle with the giant squid (or poulpe) in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea remains a benchmark for creature features.

👉 See also: Cuatro estaciones en la Habana: Why this Noir Masterpiece is Still the Best Way to See Cuba

Interestingly, Verne was influenced by real-world sightings. In 1861, the French dispatch steamer Alecton actually encountered a giant squid near Tenerife and tried to capture it. They even managed to get a harpoon into it before the creature slipped away, leaving only a piece of its tail behind. Verne took that kernel of truth and turned it into a nightmare. He didn't just invent monsters; he extrapolated from the biological reality of his time.

The book isn't just about monsters, though.

It’s about the cost of genius. Nemo lives in a museum of his own making. The Nautilus is filled with masterpieces of art and a library of 12,000 books. He’s surrounded by the best of humanity while rejecting humanity itself. This contradiction is what makes the story more than just an adventure novel. It’s a psychological study. Aronnax is caught between his fascination with the science and his horror at Nemo’s occasional acts of cold-blooded violence, like when the Captain rams a ship to seek revenge for his lost family.

Modern Science vs. Verne’s Vision

Is the science of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea actually accurate? Sorta.

Verne was a stickler for research. He read the works of oceanographers like Matthew Fontaine Maury, often called the "Father of Modern Oceanography." When Nemo describes the currents and the salinity of the water, he’s using the cutting-edge data of the 19th century. Of course, some of it is pure fiction. You can’t just walk around on the ocean floor at 30,000 feet in a simple diving suit without being crushed by the atmospheric pressure. Biology also works differently than Verne imagined; he populated the deeps with way more life than actually exists in the high-pressure, nutrient-poor zones of the midnight sea.

✨ Don't miss: Cry Havoc: Why Jack Carr Just Changed the Reece-verse Forever

But the spirit of the invention was spot on.

- Submarines now use air scrubbers to stay submerged for months.

- We use sonar (though Verne’s version was more visual).

- Electric propulsion is the gold standard for stealth.

The Nautilus was a precursor to the USS Nautilus, the world's first operational nuclear-powered submarine, launched in 1954. Life imitating art? Absolutely. The Navy even kept a copy of the book on board.

The Cultural Ripple Effect

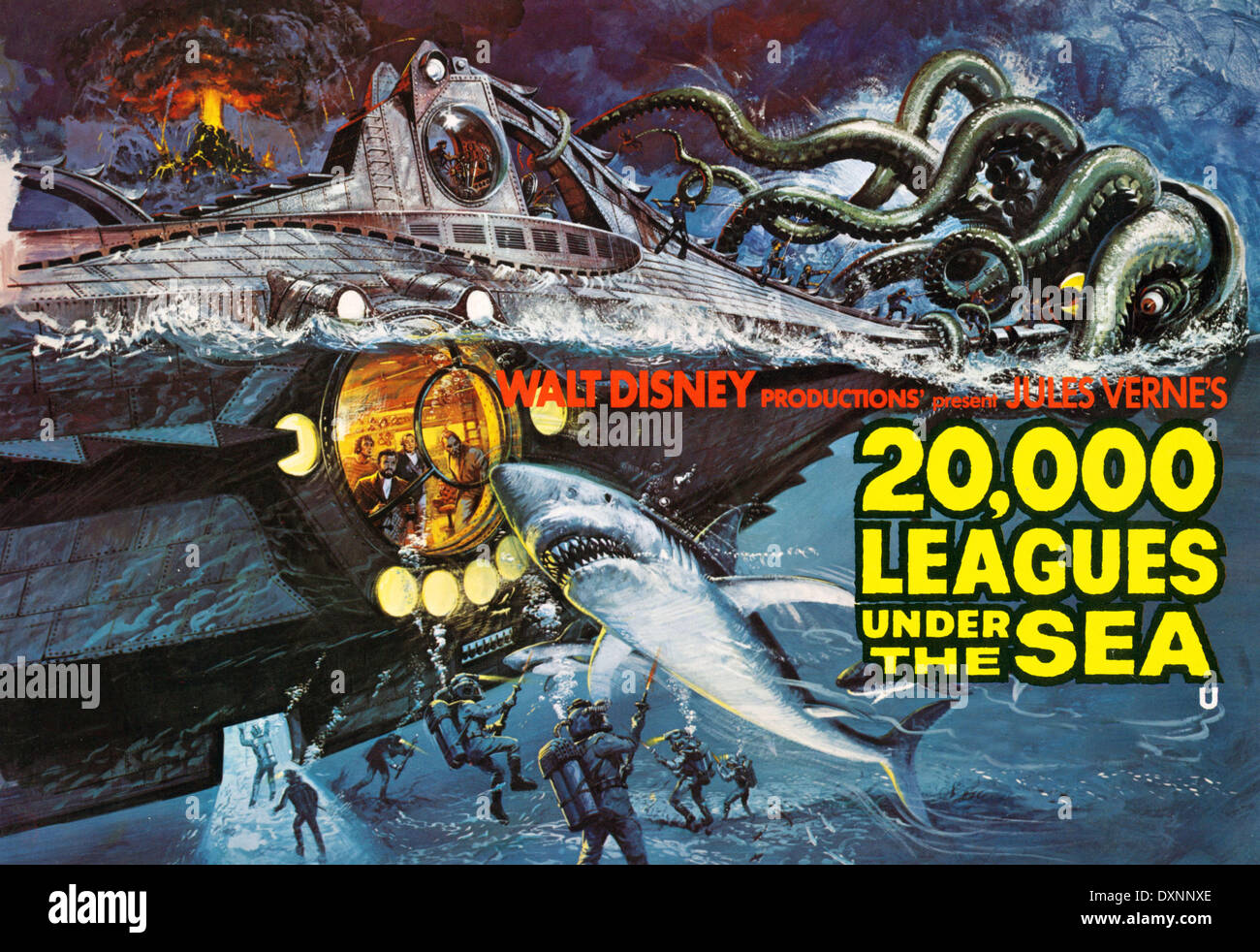

You can see the DNA of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea everywhere in modern entertainment. From the aesthetic of BioShock’s underwater city of Rapture to the character of Tony Stark, the "isolated genius with world-changing tech" trope started here. Disney’s 1954 film adaptation solidified the visual of the Nautilus—that riveted, Victorian-punk look that basically birthed the entire Steampunk genre. James Mason’s performance as Nemo gave the character a tragic, sophisticated edge that people still reference when writing complex villains.

But there’s a darker side to the legacy. Nemo’s rejection of society was a protest against imperialism. In the original manuscript, Verne wanted Nemo to be a Polish nobleman seeking revenge against the Russian Empire for the slaughter of his family during the January Uprising. His publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, was worried about offending the Russian market (and diplomatic relations), so Nemo’s origins were left vague until the sequel, The Mysterious Island, where he was revealed to be an Indian Prince (Prince Dakkar) fighting British colonial rule. This shift changed the subtext of the book from a European political squabble to a global anti-colonial statement.

Lessons From the Deep

If you're looking to revisit this world or explore the themes Verne laid out, there are a few ways to engage with the material beyond just reading the book. Honestly, the best way to understand the "vibe" of the Nautilus is to look at modern deep-sea exploration footage from organizations like NOAA or the Nautilus Live expeditions (named after the book, obviously).

🔗 Read more: Colin Macrae Below Deck: Why the Fan-Favorite Engineer Finally Walked Away

- Read the right translation. Many early English versions of the book were heavily "sanitized" or poorly translated, cutting out the scientific details and toning down Nemo’s politics. Look for the William Butcher translation for the most accurate experience.

- Watch the 1954 Disney film. Even if the effects are dated, the production design is legendary. The pipe organ scene alone captures the gothic, lonely atmosphere of the ship perfectly.

- Explore the Steampunk community. If you love the aesthetic of brass, rivets, and Victorian tech, this book is the holy grail.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea isn't a story about a boat. It’s a story about the boundaries of human knowledge and the danger of going too far alone. Nemo had the world at his fingertips, but he had no one to share it with, which is a warning that feels more relevant in our digital age than it ever did in 1870.

To truly appreciate the depth of Verne's work, compare his descriptions of the "Arabian Tunnel" or the South Pole (which he thought was an open sea, a common theory at the time) with modern maps. Seeing where he was right—and where he was wildly, spectacularly wrong—is half the fun. It reminds us that our own "cutting edge" science will probably look just as quaint and imaginative to people 150 years from now.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Aquanaut

If you want to dive deeper into the world of Jules Verne and marine exploration, start by tracking the real-life Nautilus. The Ocean Exploration Trust operates the E/V Nautilus, which live-streams deep-sea dives. It’s the closest thing we have to Nemo’s view of the world. Additionally, check out the work of Dr. Robert Ballard—the man who found the Titanic—who has often cited Verne as a primary inspiration for his career. Understanding the history of the submarine, from the Turtle during the American Revolution to the modern Ohio-class boats, provides the necessary context to see just how radical Verne's fictional ship really was.

Source References:

- Verne, J. (1870). Vingt mille lieues sous les mers.

- Miller, W. J. (2006). The Annotated Jules Verne.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) - Deep Sea History Archives.

- The Jules Verne Museum, Nantes, France.