Walk into any modern tech startup and you’ll likely see it. A sleek, silver rocket. A glass-domed city. Maybe a robot with a chest full of blinking lights. It’s funny because, honestly, we’re living in the "future" now, yet our collective imagination is still stuck in a loop. We are still obsessed with 1950s science fiction art.

Think about it.

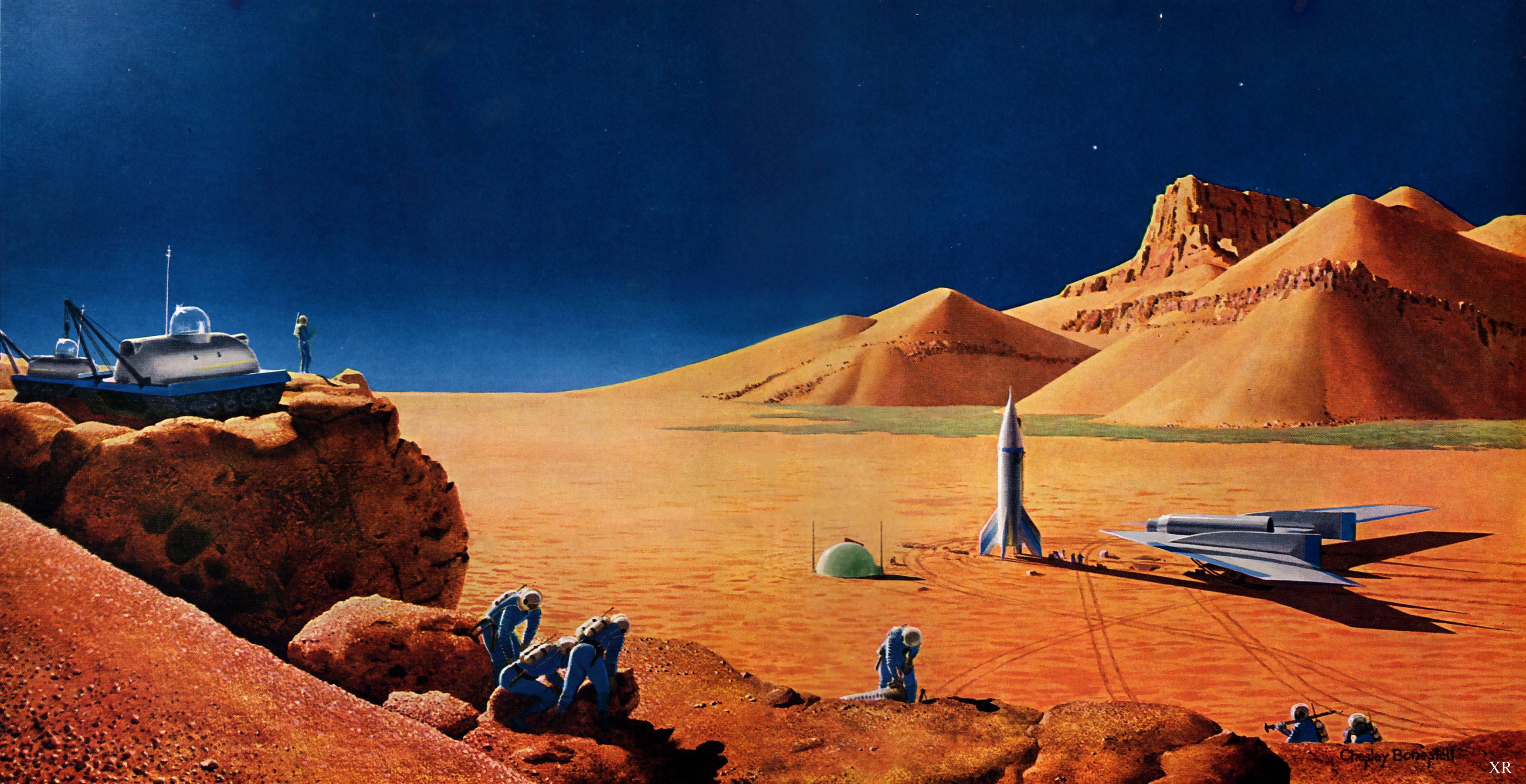

The decade was a pressure cooker. You had the post-war boom, the terrifying shadow of the mushroom cloud, and the sudden, frantic realization that we were actually going to put a man on the moon. It wasn't just about drawing cool ships. It was about survival and curiosity. Artists like Chesley Bonestell or Frank Kelly Freas weren't just guessing; they were basically architects of a tomorrow that felt five minutes away.

The Blueprint of the Space Race

If you want to understand where this all started, you have to look at Collier’s magazine. Specifically, the "Man Will Conquer Space Soon!" series from 1952. This wasn't some niche hobbyist stuff. This was mainstream. Chesley Bonestell, who is basically the grandfather of modern space art, teamed up with scientists like Wernher von Braun. They didn't just paint "pretty stars." They calculated orbits. They looked at how light would actually hit the craters of the moon.

Bonestell’s work was so realistic that it tricked the public's brain. Before the first satellite ever beeped in orbit, people felt like they’d already been there. His 1949 book, The Conquest of Space, with Willy Ley, basically served as a visual NASA pitch deck before NASA even existed.

✨ Don't miss: America's Got Talent Semi-Finals: The Heartbreak and Hype Nobody Talks About

It’s wild.

You look at those paintings and see these massive, wheel-shaped space stations. It’s elegant. It’s terrifying. It’s also wildly different from the grimy, "lived-in" sci-fi we got later in the 70s with Star Wars. This was the era of the "clean" future. Everything was polished chrome and optimism, even if that optimism was masking a deep-seated fear of nuclear annihilation.

Magazines, Pulps, and the "B-Movie" Aesthetic

While Bonestell was being "serious," the pulp magazines were having a total blast. Magazines like Astounding Science Fiction, Galaxy, and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction were the lifeblood of the genre. This is where 1950s science fiction art got weird and colorful.

Ed Emshwiller (often signing as "Emsh") and Frank Kelly Freas were the kings here. Freas had this incredible ability to inject humor and humanity into aliens. You’ve probably seen his work without realizing it. He’s the guy who painted the "sad robot" holding a dead pilot for Astounding in 1953—an image so iconic that Queen literally put it on the cover of their News of the World album decades later.

Contrast that with the "Bug-Eyed Monsters" (BEMs).

The 50s loved a good BEM. It was a trope for a reason. These covers usually featured a giant, green, multi-limbed creature clutching a woman in a metallic bikini. It’s easy to dismiss this as kitsch. But look closer. The technical skill in the airbrushing and the composition is often top-tier. Artists like Earle Bergey were masters of the human form, even if they were putting that form in ridiculous, logic-defying space suits.

🔗 Read more: Behind Her Eyes Series: Why That Ending Still Disturbs Everyone

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Raygun Gothic" Style

People often lump all 50s sci-fi into one "cheesy" bucket. That’s a mistake.

There’s a specific sub-genre called Raygun Gothic. It’s all about those fins. You see it in the cars of the era—the Cadillac Eldorado with the massive tailfins—and you see it in the rockets. The belief was that everything needed to be aerodynamic, even in the vacuum of space where aerodynamics literally don't matter.

It was a vibe.

It was about speed. Modernity. Moving away from the dusty, earthbound struggles of the Great Depression and World War II. If it looked like it was moving 1,000 miles per hour while standing still, it was "the future."

The Dark Side of the Chrome

We can't talk about 1950s science fiction art without talking about the Bomb.

The Cold War was the backdrop for every single brushstroke. When you see those paintings of domed cities, they aren't just for aesthetics. They are bunkers. They represent a desire to be shielded from a radioactive atmosphere. The "alien invasion" trope was almost always a thin veil for the "Red Scare."

Artists like Richard Powers took a different route. Instead of the literal rockets and robots, he went surreal. His covers for Ballantine Books in the mid-50s looked like Salvador Dalí went to Mars. It was abstract. He captured the psychological dread of the era—the feeling that the world was changing so fast we couldn't even recognize ourselves in the mirror anymore.

Powers' work suggests that the future isn't just a place we go; it’s a place that might break our brains.

The Technology of the Art Itself

How did they actually make this stuff?

No Photoshop. No digital tablets.

It was gouache. Oil. Airbrush. Lots and lots of masking tape.

Artists had to be incredibly precise. To get those glowing "plasma" effects or the reflection of a nebula on a brass helmet, they had to understand light physics. They were often working on tight deadlines for very little pay, churning out masterpieces for a few hundred bucks that would eventually sell at auction for tens of thousands.

Take a look at the "Future Cities" often depicted in Popular Mechanics. These weren't just fantasies; they were often based on actual architectural proposals. The artists were bridges between the engineering world and the public's imagination. They made the impossible look inevitable.

Why We Can't Let Go

So, why does 1950s science fiction art still hold such a grip on us?

Maybe it’s because it represents the last time we were truly, unironically excited about the future. Today, our sci-fi is mostly dystopian. It’s all "the world is ending" and "the robots are going to kill us."

In the 50s, the robots might have been scary, but they were also cool.

📖 Related: The Roswell Delirium Cast: Why This 80s Fever Dream Works

There was a sense of agency. The idea was that if we just built a big enough rocket, we could solve any problem. That "can-do" spirit is baked into every line and every neon-colored starfield. It’s a nostalgic future. A "future that never was," as some call it.

Actionable Ways to Explore 1950s Science Fiction Art Today

If you’re looking to actually dive into this world, don't just look at Pinterest. Go to the sources.

- Hunt for "Heritage Auctions" catalogs. They often have high-res scans of original pulp art that show the actual brushstrokes and white-out marks. Seeing the "flaws" makes the art feel much more real.

- Check out the "Art of Chesley Bonestell" documentary. It’s a deep dive into how his work influenced the actual moon landing.

- Look for "The Art of Richard Powers" by Jane Frank. If you want to see the weird, surreal side of the decade, this is the gold standard.

- Visit the Museum of Flight in Seattle. They often have exhibits specifically on the intersection of 50s concept art and real aerospace engineering.

The best way to appreciate this stuff is to look at it through the eyes of someone in 1955. Forget what you know about SpaceX or the ISS. Imagine you’ve never seen a photo of Earth from space. Now, look at a Bonestell painting.

It’s not just art. It’s a map to a place we’re still trying to reach.

To truly understand the impact of this era, start by comparing the concept art for the 1956 film Forbidden Planet—specifically the Krell underground machinery—to modern industrial design. You’ll see the DNA of the 1950s in everything from the original iMac to the latest Cybertruck. The future, it turns out, was designed seventy years ago.