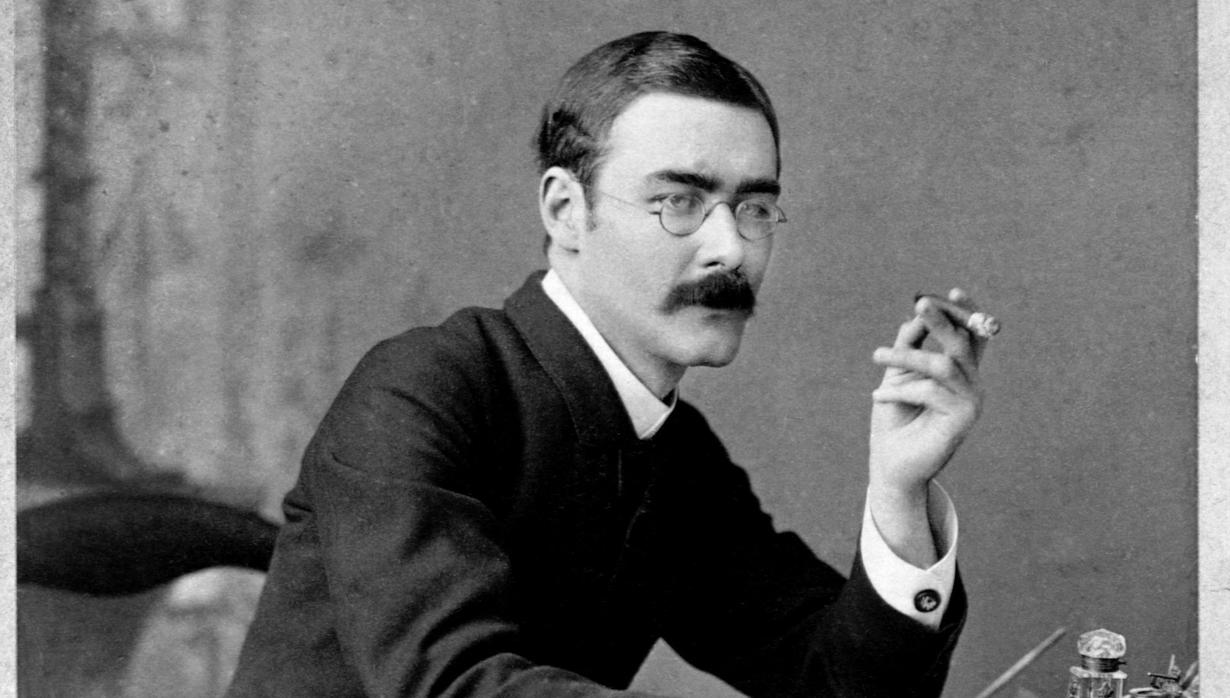

You know the name. You probably grew up with the songs from the Disney movie or maybe you had to memorize that "If—" poem in middle school. But if you actually sit down and ask who was Rudyard Kipling, the answer is a lot messier than a talking bear or a catchy rhyme. He was a rockstar. Truly. In the late 1800s, he was basically the most famous writer on the planet, a Nobel Prize winner who turned down a knighthood because he thought he was above it.

He was also a man deeply out of step with the world he helped create.

He was born in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1865. That’s the starting point. If you want to understand his writing, you have to understand that he felt like a stranger everywhere. To the British in England, he was a "colonial" with a weird accent and strange ideas. To the people in India, he was a representative of the British Raj—the occupying force. He lived in this weird, uncomfortable middle ground, and that tension is exactly what made his stories so electric.

The lonely child who invented Mowgli

People forget that The Jungle Book wasn't just a fun animal story. It was born out of a pretty traumatic childhood. When Kipling was six, his parents sent him from the warmth of India to a "harrowing" foster home in Southsea, England. He called it the "House of Desolation." He was bullied. He was lonely. He almost went blind because no one realized he needed glasses.

That feeling of being an outsider? That’s Mowgli.

Mowgli isn't just a kid who hangs out with wolves; he’s a boy who doesn’t belong to the pack and doesn’t belong to the village. He's stuck between two worlds. When Kipling eventually returned to India as a young journalist in his late teens, he was looking for a home he’d lost. He spent his nights wandering the streets of Lahore, drinking in the sights and smells, and writing feverishly for the Civil and Military Gazette.

He worked like a dog. Honestly, the output was insane. He was churning out poems and short stories that captured the grit of soldier life and the mysticism of the Indian landscape. He didn't write about "the noble officer"; he wrote about the sweaty, swearing, terrified private in the trenches. That’s why the public loved him. He felt real.

Why we still argue about who was Rudyard Kipling

We have to talk about the elephant in the room: imperialism. You can’t discuss Kipling without mentioning "The White Man's Burden." It's a phrase that has aged incredibly poorly. To a modern reader, it’s cringey at best and openly racist at worst.

💡 You might also like: Actor Most Academy Awards: The Record Nobody Is Breaking Anytime Soon

But here’s the nuance that experts like Charles Allen (who wrote Kipling Sahib) point out: Kipling was a man of the British Empire, through and through. He believed in the "civilizing mission." He thought the British were bringing order to chaos. He was wrong, of course, but he wasn't just a cartoon villain. His relationship with India was a weird mix of genuine love and condescending paternalism.

He spoke Hindi. He knew the folklore. He respected the bravery of the soldiers he met, regardless of their skin color—look at his poem "Gunga Din." He portrays a water carrier as a hero who is "better" than the white narrator. Yet, in the same breath, he supported a system that denied those very people their freedom.

It’s this contradiction that makes him so frustrating to study today. He was a brilliant observer who was blinded by his own ideology.

The American years and the Vermont connection

Did you know Kipling lived in Vermont? It sounds fake, but it’s true. He married an American woman, Carrie Balestier, and they built a house called Naulakha in Dummerston.

This is where he wrote The Jungle Book.

Think about that for a second. The most famous book about the Indian jungle was written in the freezing snow of New England. He loved the privacy of America, but he eventually got into a legal feud with his brother-in-law (who was a bit of a drunk and a hothead) and fled back to England. He never really got over his time in the States, but he couldn't stay. He was always running from somewhere.

The Nobel Prize and the loss that broke him

In 1907, Kipling became the first English-language writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was only 41. To this day, he’s still the youngest person to ever receive it. He was at the absolute peak of his powers.

📖 Related: Ace of Base All That She Wants: Why This Dark Reggae-Pop Hit Still Haunts Us

Then came the Great War.

Kipling was a massive hawk. He pushed for the war. He used his writing to recruit young men to the front lines. He even used his influence to get his son, John, a commission in the Irish Guards, even though John had terrible eyesight and had been rejected by the military several times.

John went missing in action during the Battle of Loos in 1915. He was 18.

Kipling spent the rest of his life haunted by it. He and Carrie spent years searching for John’s body, visiting hospitals, and interviewing survivors. They never found him while they were alive (his grave wasn't identified until 1992). This loss changed Kipling's writing. It became darker, more haunted, and more complex. If you read his later stories like "The Gardener," you see a man absolutely shattered by guilt. He knew he had sent his son to his death.

The craft: Why his writing still works

Forget the politics for a second and just look at the prose. Kipling was a master of the "short, sharp shock." He didn't waste words.

- The Voice: He had an ear for dialect that was unmatched. He could make a cockney soldier sound like a real person, not a caricature.

- The Atmosphere: He could describe the heat of an Indian afternoon so well you’d swear you were sweating.

- The Economy: He learned his trade as a newspaperman. He knew how to hook a reader in the first ten words.

His poetry has a beat to it. It’s "balladry." It was meant to be read aloud, chanted, or sung. That’s why so many of his phrases have leaked into the English language. "The female of the species is more deadly than the male"? That’s Kipling. "East is East, and West is West"? Kipling. "The ship that found herself"? Also him.

Re-evaluating the "Prophet of Empire"

So, how do we handle him in 2026?

👉 See also: '03 Bonnie and Clyde: What Most People Get Wrong About Jay-Z and Beyoncé

Some people want to cancel him entirely. They see the imperialism and the "Burden" and they want to toss the books in the bin. Others want to ignore the bad stuff and just focus on the talking wolves. Both approaches are kinda lazy.

The reality is that Kipling was a genius who was also a product of a very specific, very flawed era. You can admire his ability to describe a sunset or a tiger's prowl while also acknowledging that his political views were harmful. We can hold both those things in our heads at once.

He was a man who felt deeply. He loved India with a passion that most British officials couldn't understand, but he also supported the boots on the ground that kept India under British thumbs. He was a father who lost his son to a war he cheered for. He was a Nobel laureate who felt like a failure.

Getting started with Kipling (The non-Disney version)

If you want to actually understand who was Rudyard Kipling, don't just watch the movie. You need to get into the dirt of his actual writing.

- Read Kim: This is widely considered his masterpiece. It’s a spy novel, a travelogue, and a spiritual journey all rolled into one. It captures the "Great Game" of espionage in 19th-century India better than anything else ever written.

- Check out the Plain Tales from the Hills: These are short, punchy stories about life in colonial India. They’re cynical, funny, and sometimes very dark.

- Listen to his poetry: Don't just read "If—" on a poster. Find a recording of "The Mary Gloster" or "Danny Deever." You’ll hear the rhythm that made him the most popular poet of his age.

- Visit the Sussex Downs: If you’re ever in England, go to Bateman’s. It was his home for the last thirty years of his life. You can see his Rolls Royce and the desk where he wrote. It feels heavy with history.

Kipling died in 1936. By then, the world he knew was already disappearing. The British Empire was crumbling, and the "modern" writers like T.S. Eliot and James Joyce had made his style look old-fashioned. But here we are, nearly a century later, still talking about him. You can’t kill a good story, and Kipling, for all his many faults, was one of the greatest storytellers who ever lived.

He remains a ghost in our cultural machine—reminding us of where we came from, the mistakes we made, and the power of a perfectly placed word. To understand him is to understand the messy transition into the modern world.

Actionable Next Steps

- Read "The Man Who Would Be King": It’s a short story about two rogues who try to become kings of a remote part of Afghanistan. It’s the perfect distillation of Kipling’s views on power, greed, and the impossibility of empire.

- Compare and Contrast: Watch the 1975 film adaptation of the same name starring Sean Connery and Michael Caine. It’s a rare example of a movie that captures the grit and the irony of the original text perfectly.

- Explore the Archive: Use the Kipling Society website. It is an incredible, old-school resource that has annotations for almost every single thing he wrote, helping you decode the Victorian slang and historical context that can be confusing today.