You probably learned the basics in third period chemistry. An atom looks like a tiny solar system. There’s a sun in the middle called the nucleus, and some planets orbiting around it. It's a clean image. Simple. But honestly? It’s also mostly wrong. When people ask which subatomic particles are found in the nucleus, the textbook answer is protons and neutrons. That's the baseline. If you're taking a middle school quiz, stop there and you'll get the A.

But if you actually peer into the heart of an atom, things get messy. Fast.

The nucleus isn't just a static bag of marbles. It is a vibrating, chaotic, high-energy environment held together by forces so powerful they defy common sense. We call the main residents nucleons. These are your protons and neutrons. However, if you really want to understand what's happening at the center of your being—and the center of every coffee mug, star, and smartphone on Earth—you have to look at the "glue" and the "ghosts" that live there too.

The heavy hitters: Protons and Neutrons

Basically, the nucleus is where all the "stuff" is. While electrons are incredibly important for chemistry and electricity, they have almost no mass. If an atom were the size of a football stadium, the nucleus would be a small marble in the middle, yet that marble would weigh 99.9% of the entire stadium's mass.

Protons are the identity markers. They carry a positive electrical charge. The number of protons determines what element you’re looking at. One proton? You’ve got Hydrogen. Six? That’s Carbon. If you manage to shove a 79th proton into a nucleus, you’ve literally made gold. This is the atomic number. It’s the DNA of the universe.

Then you have neutrons. As the name suggests, they’re neutral. No charge. They were the hardest to find because they don't react to electric fields. James Chadwick finally pinned them down in 1932, long after we knew about protons. You might think they’re just "extra weight," but they are actually the peacemakers.

Think about it: protons are all positively charged. In physics, like charges repel. If you try to jam a bunch of protons together, they want to fly apart with incredible violence. Neutrons act as a sort of nuclear buffer. They provide extra "Strong Nuclear Force" without adding more electromagnetic repulsion. Without neutrons, the universe would basically just be a giant cloud of lone protons (hydrogen) because nothing else could stay stuck together.

What’s inside the nucleons?

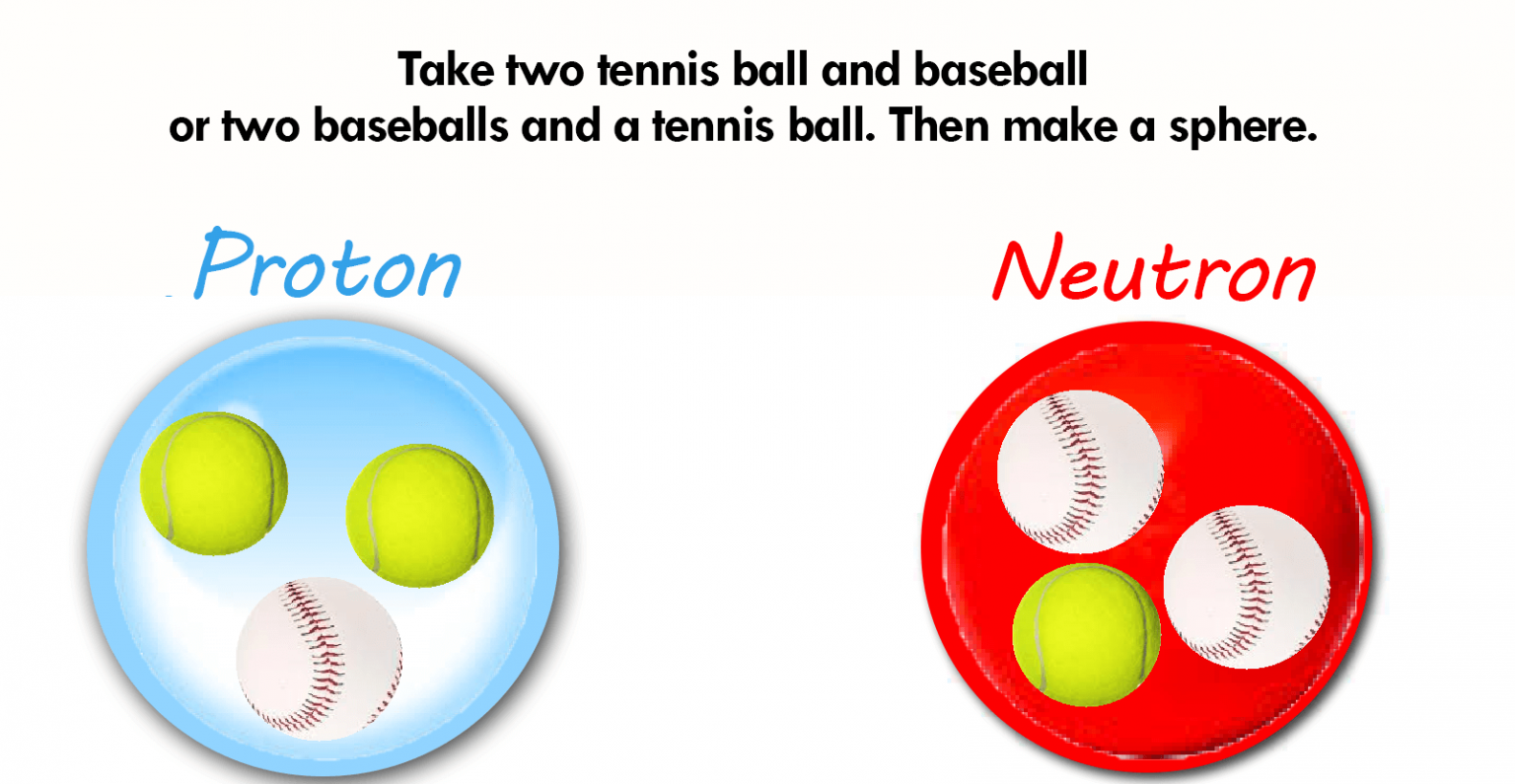

Here is where the "standard" answer to which subatomic particles are found in the nucleus starts to fall apart. Protons and neutrons aren't solid. They aren't fundamental. They are made of even smaller bits called quarks.

Specifically, they are made of Up quarks and Down quarks.

- A proton is two Ups and one Down.

- A neutron is one Up and two Downs.

But wait. If you add up the mass of those three quarks, you only get about 1% of the mass of the proton. Where is the other 99%? It’s in the energy of the gluons.

The Sticky Stuff: Gluons and Mesons

Gluons are carrier particles. They "carry" the strong force. They are constantly zipping between quarks, "gluing" them together. In a very real sense, the nucleus is mostly made of binding energy. When we talk about nuclear energy, we are talking about tapping into that frantic, high-speed exchange.

There is another particle you’ve probably never heard of called the pion (or pi-meson). Hideki Yukawa, a Japanese physicist, predicted these in the 1930s. He realized that for protons and neutrons to stick to each other (not just holding themselves together internally), they had to be tossing something back and forth. Pions are those "baseballs" being thrown between nucleons.

So, technically, at any given microsecond, a nucleus is full of quarks, gluons, and a cloud of virtual pions. It’s not a quiet neighborhood. It’s a mosh pit.

The weirdness of "Virtual Particles"

Quantum field theory tells us that the vacuum isn't empty, and neither is the nucleus. Because there is so much energy packed into such a tiny space, "virtual" particles are constantly popping in and out of existence.

You’ve got pairs of quarks and anti-quarks appearing and annihilating in less than a billionth of a trillionth of a second. They don't stay. They don't add to the "count" of particles in a way that changes the element, but they contribute to the internal pressure and magnetic properties of the nucleus.

📖 Related: Why a Rugged Keyboard Case for iPad is Actually Worth the Extra Weight

If you're asking which subatomic particles are found in the nucleus from a purely physical perspective, you have to acknowledge this "sea" of temporary residents. It’s like a crowded subway station; there are the people who live there (protons and neutrons) and a thousand people just passing through (gluons, pions, virtual pairs).

Why the "Neutron Star" matters to this conversation

To see these particles in their most extreme state, we look to the sky. When a massive star dies, its gravity is so strong it crushes the atoms. The electrons get squeezed into the protons.

When a negative electron hits a positive proton, they cancel out and turn into a neutron (and a neutrino). The result is a Neutron Star. It is essentially one giant atomic nucleus the size of a city. It is the densest object in the known universe besides a black hole. A sugar cube of this "nucleus material" would weigh about a billion tons.

This helps us realize that the distinction between these particles is often just a matter of energy and pressure. Under enough stress, the boundaries between "this particle" and "that particle" get very blurry.

The limits of what we know

We still don't fully understand the "EMC Effect." Back in the 80s, researchers at CERN noticed that quarks inside a large nucleus (like Lead) behave differently than quarks inside a single proton (like Hydrogen).

Why? We don't really know.

It suggests that when nucleons are packed together, they might "overlap" or change their internal structure. This is the cutting edge of nuclear physics. We are realizing that the nucleus isn't just a collection of independent parts; it's a collective system that changes based on who else is in the room.

Summary of the "Resident" List

To keep it straight, here is the hierarchy of what lives in that tiny central core:

- The Residents: Protons and Neutrons (Nucleons).

- The Components: Quarks (Up and Down).

- The Workers: Gluons (carrying the strong force).

- The Intermediaries: Pions (keeping the nucleons stuck together).

- The Guests: Virtual particle-antiparticle pairs.

Practical Steps for the Curious

If you're looking to go deeper than a blog post, you should check out the Jefferson Lab resources or the Brookhaven National Laboratory website. They are currently using particle accelerators to "map" the inside of the nucleus.

- Check out a Table of Isotopes. It’ll show you how changing the number of neutrons (the "peacemakers") changes the stability of the nucleus. Some versions of an element are stable, while others are "radioactive" because they have too many or too few neutrons to keep the peace.

- Look up "Binding Energy Per Nucleon" graphs. This explains why we can get energy from splitting big atoms (fission) like Uranium, but also from fusing small atoms (fusion) like Hydrogen. It all comes down to how tightly those particles in the nucleus are packed.

- Explore "The Standard Model." This is the "map" of all subatomic particles. It’ll help you see where the nucleus fits into the bigger picture of leptons, bosons, and quarks.

Understanding the nucleus is basically understanding the engine room of reality. It's dense, it's violent, and it's held together by forces that make gravity look like a joke. Next time you look at a periodic table, remember that those numbers aren't just math—they're a count of the tiny, vibrating residents of a world we can barely see.

---