Ever stared at a laser pointer and wondered why that specific shade of red looks the way it does? It isn't just a random choice by a manufacturer in a factory somewhere. That bright, crisp crimson usually sits right at the 650 nanometer mark. But if you’re trying to plug that value into a physics equation or a CAD program, "nanometers" won't cut it. You need the standard unit. Converting 650 nm to meters is one of those tiny mathematical hurdles that pops up in everything from high school lab reports to the engineering of fiber-optic networks.

It's a small number. Like, incredibly small.

To get the conversion out of the way immediately: 650 nanometers is exactly $6.5 \times 10^{-7}$ meters. In decimal form, that is 0.00000065 meters.

The math behind the tiny shift

Most people get tripped up by the "nano" prefix. In the SI system (International System of Units), prefixes are powers of ten. "Nano" comes from the Greek word nanos, meaning dwarf. It represents one-billionth of a unit. So, one nanometer is $1 \times 10^{-9}$ meters.

When you have 650 of them, you’re basically doing a simple multiplication: $650 \times 0.000000001$.

If you’re doing this for a homework assignment or a quick engineering spec, just move the decimal point nine places to the left. Start at the end of 650. Move it three spots, and you’re at 0.650 micrometers (microns). Move it another six spots, and you’ve arrived at your meter value. Honestly, it’s easier to just remember that you’re dealing with seven zeros after the decimal if you include the one before the point, but most pros just use scientific notation because writing out all those zeros is a recipe for a typo.

Why does 650 nm matter anyway?

You might think 650 nm is just a random point on a graph. It isn't. This specific wavelength is a "sweet spot" for several massive industries.

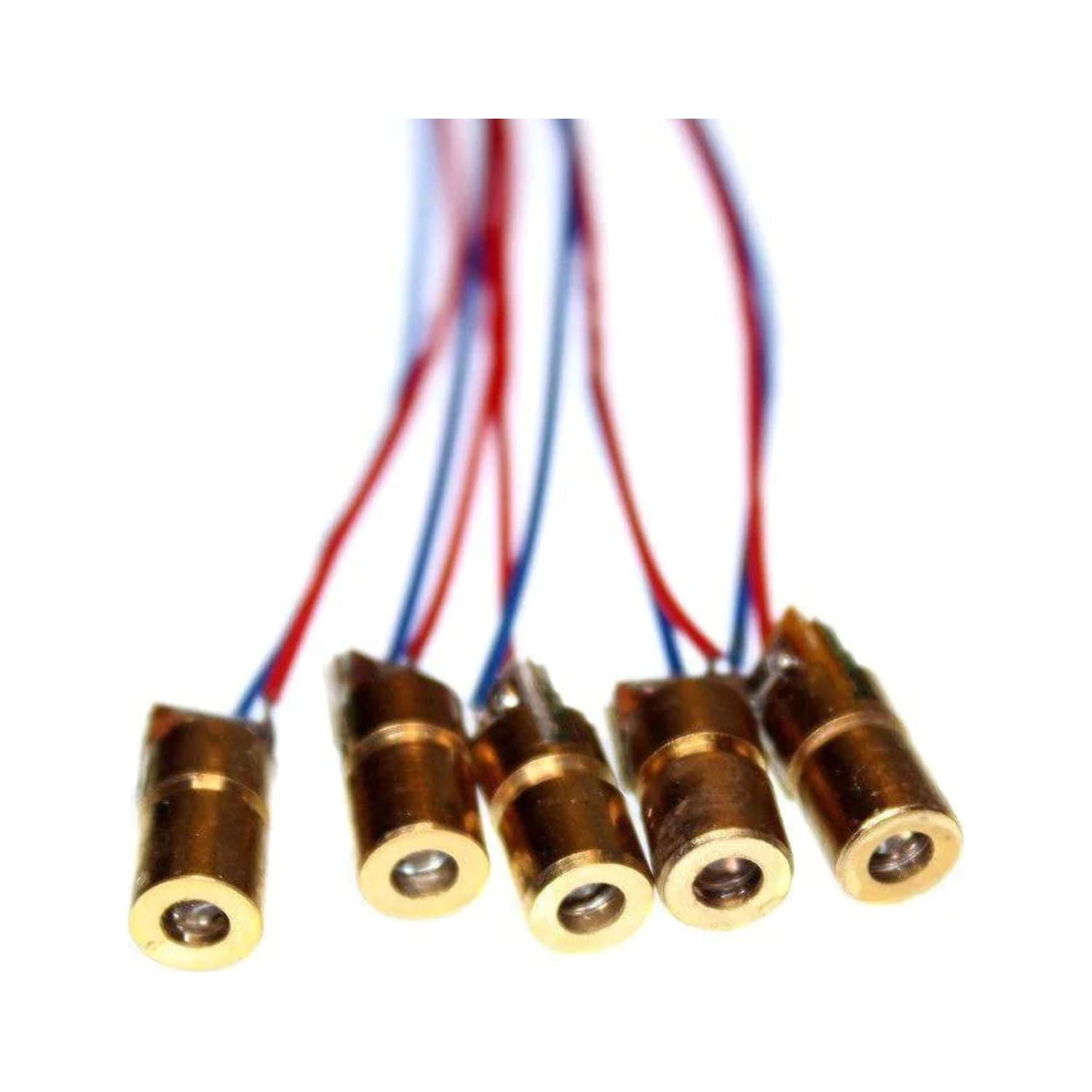

Take DVD players. Remember those? The red laser used to read a standard DVD operates at roughly 650 nm. Engineers chose this because it was a wavelength short enough to focus on the tiny pits of data on a disc, but long enough that the laser diodes were cheap and reliable to produce in the late 90s and early 2000s. If they had used a longer wavelength, the "spot" of the laser would have been too big, and we wouldn't have been able to fit 4.7 GB on a single side.

✨ Don't miss: What Does Geodesic Mean? The Math Behind Straight Lines on a Curvy Planet

Then there’s the medical side of things.

Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT) often utilizes the 650 nm range. Why? Because human tissue has a "window" of transparency. Our skin, blood, and fat absorb different colors of light at different rates. At 650 nm, the light penetrates deep enough into the dermis to stimulate mitochondria without being instantly absorbed by the water in our cells or the hemoglobin in our blood. It’s a very specific biological handshake. Dr. Michael Hamblin, a well-known researcher formerly at Harvard Medical School, has published extensively on how this "red light" range influences cellular behavior, often referred to as photobiomodulation.

The color of the world

Visible light for humans roughly spans from 380 nm (violet) to about 750 nm (deep red).

At 650 nm, you are firmly in the "red" zone. It’s a bright, distinct red. If you go much higher, say toward 700 nm, the light starts to look "dimmer" to the human eye even if the power output is the same, because our eyes are losing sensitivity as we approach the infrared spectrum. If you go lower, toward 600 nm, the light starts looking orange.

So, when you convert 650 nm to meters, you aren't just moving decimals. You are defining a specific packet of energy. In physics, wavelength is inversely proportional to energy. Since red light has a longer wavelength than blue light (which is around 450 nm), it carries less energy per photon.

Common pitfalls in the conversion process

I’ve seen plenty of people confuse nanometers with micrometers (microns). A micron is $10^{-6}$ meters. If you accidentally convert 650 nm to $0.00000065$ microns, you’ve just missed the mark by a factor of a thousand. In the world of optics or semiconductor manufacturing, a thousandfold error is the difference between a working chip and a useless piece of silicon.

Another thing to watch for is the medium.

🔗 Read more: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

Light changes its wavelength depending on what it’s traveling through. The "650 nm" we talk about is the wavelength in a vacuum (or effectively, air). If that light enters a piece of glass or water, it slows down. Because the frequency remains constant, the wavelength actually shrinks. So, while the "color" (the frequency) stays the same, the physical length of the wave in meters changes. If you’re designing a lens or an underwater sensor, you have to account for the refractive index of the material.

Real-world application: Plastic Optical Fiber (POF)

Communication isn't all about glass fibers. In many home networks or automotive data links, we use Plastic Optical Fiber. Unlike the glass stuff used for transoceanic cables, POF is thick and rugged. It also happens to have a transmission "window" right around 650 nm.

Using 650 nm light in these fibers allows for the use of inexpensive LEDs rather than expensive, temperature-sensitive laser diodes. If you work in industrial automation, you've likely seen these red lights glowing at the end of a fiber optic cable. When you're calculating the attenuation (signal loss) per meter of that cable, you’re going to be using that $6.5 \times 10^{-7}$ meter figure in your loss equations.

How to use this value in calculations

If you’re a student or an engineer, you’re likely using the 650 nm to meters conversion to find frequency or energy.

The speed of light ($c$) is roughly $3 \times 10^8$ meters per second.

To find the frequency ($f$), you use the formula: $f = \frac{c}{\lambda}$

Where $\lambda$ is your wavelength in meters.

$f = \frac{3 \times 10^8}{6.5 \times 10^{-7}}$

This gives you a frequency of approximately 461 Terahertz. See? Without converting to meters first, the units won't cancel out, and your answer will be off by several orders of magnitude.

💡 You might also like: 1 light year in days: Why our cosmic yardstick is so weirdly massive

Actionable steps for precision

If you’re working on a project that involves this wavelength, don't just wing the math.

Double-check your units. Always convert to the base unit (meters) before plugging values into any standard physics formula.

Consider the source. Is your light source exactly 650 nm? Most cheap laser diodes have a tolerance of $\pm 10$ nm. A "650 nm" laser might actually be 658 nm. In most cases, this doesn't matter. But if you're doing precision interferometry or spectroscopy, that small shift matters a lot.

Use scientific notation. Stop writing 0.00000065. It's $6.5 \times 10^{-7}$. It's cleaner, harder to misread, and it’s how every professional calculator handles the data anyway.

Verify your material. If the light is passing through anything other than air, remember to divide your vacuum wavelength by the refractive index of the material ($n$) to find the actual physical wavelength inside that medium.

Converting 650 nm to meters might seem like a trivial task, but it is the bridge between the visible world we see and the mathematical reality of the universe. Whether you're timing a signal in a fiber optic line or calculating the photon energy for a skin treatment device, that decimal move is the most important step in the process.

Stay precise. Keep your units consistent. And maybe appreciate that the red light in your grocery store scanner is a wave of energy exactly 0.00000065 meters long.

Key Reference Check

- 1 nanometer (nm) = $10^{-9}$ meters

- 650 nm = $650 \times 10^{-9}$ meters

- Scientific Notation = $6.5 \times 10^{-7}$ meters

- Decimal = 0.00000065 meters

- Micrometers = 0.65 $\mu$m

When setting up your next project, ensure your software is set to the correct SI prefix. Most modern CAD and simulation tools (like Zemax or COMSOL) allow you to input "650nm" directly, but they perform the conversion to meters internally for the actual physics engine. If you're writing your own scripts in Python or MATLAB, define a constant for the nanometer multiplier to avoid hard-coding zeros and making a mistake that’s hard to find later.

For those in the manufacturing space, keep an eye on the "binning" of your LEDs or lasers. A 650 nm spec is often just a nominal value. If your application depends on a specific absorption peak, always ask the supplier for the spectral distribution graph.