You're huffing. Your chest feels like a drum set in a heavy metal solo. Maybe you're glancing at your Apple Watch or Fitbit every thirty seconds, wondering if that 165 bpm reading means you're a fitness god or about to see stars. Honestly, most people just guess. They see a high number and think, "Cool, I'm working hard," or they see a low one and feel like they're failing. But what is a good pulse rate during exercise actually looks different for a 22-year-old marathoner than it does for a 55-year-old just trying to lower their blood pressure.

It's not a single number. It's a moving target.

If you want the short version, a "good" rate is usually between 50% and 85% of your maximum heart rate. But that's kinda like saying a good temperature for food is "not frozen." It doesn't tell the whole story. Your heart is an adaptable muscle, and its rhythm tells you exactly which energy system you're burning through—whether it's fat, glycogen, or pure desperation.

The 220-Minus-Age Myth and Better Math

We've all heard the formula. Take 220, subtract your age, and boom—there is your max heart rate. It’s everywhere. It’s in high school PE textbooks and plastered on the stickers of old treadmills. But here’s the thing: that formula was never meant to be a gold standard. It was actually derived from a compilation of about 10 different studies in the 1970s, and it can be off by as much as 10 to 12 beats per minute for a lot of people.

If you're 40, the math says your max is 180. But you might hit 192 and feel fine, or you might hit 175 and feel like you're meeting your ancestors.

Researchers like those at the Mayo Clinic and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) often suggest the Tanaka formula for a slightly more accurate "at-home" estimate. You take your age, multiply it by 0.7, and subtract that from 208. It sounds nerdy, but for older adults especially, it tends to be way more reliable.

Why your resting heart rate matters first

Before you even start sweating, look at your pulse while you're drinking coffee—or better yet, right when you wake up. A lower resting heart rate (RHR) usually means a more efficient heart. Athletes like Miguel Induráin, a legendary cyclist, reportedly had a resting heart rate in the high 20s. For us mere mortals, 60 to 100 bpm is normal. If your RHR starts climbing over a few weeks, it's actually a huge red flag that you're overtraining or getting sick. Your body is telling you it hasn't recovered before you even tie your shoes.

Understanding the Zones: Where the Magic Happens

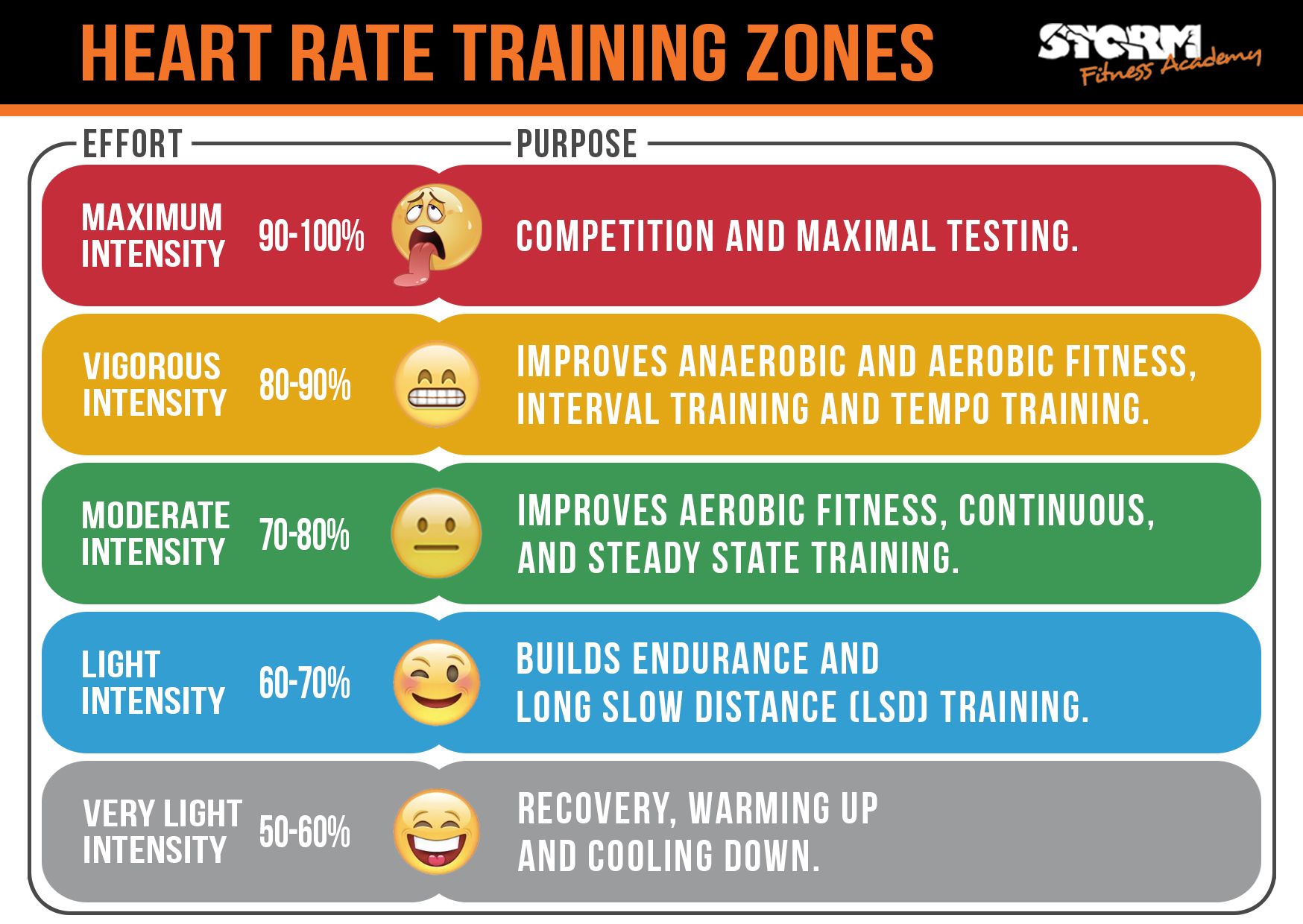

When we talk about what is a good pulse rate during exercise, we have to break it down by intensity. You don't want to be at 90% of your max for a 45-minute jog. You'll crash.

Moderate Intensity (The "Zone 2" Obsession)

Lately, everyone is obsessed with Zone 2. And for good reason. This is usually 60% to 70% of your max heart rate. It feels easy. Too easy, sometimes. You can hold a full conversation about what happened on The Last of Us without gasping.

🔗 Read more: Is the Danger of UV Light for Nails Actually Real? What the Science Says

Why do it? It builds mitochondria. It teaches your body to burn fat for fuel instead of just burning through sugar. If you’re wondering why you’re always tired after a workout, you might be spending too much time in the "gray zone"—too fast to be recovery, too slow to be a sprint.

Vigorous Intensity (The Sweat Soak)

Once you cross into 70% to 85% of your max, things get spicy. This is where cardiovascular fitness improves the most. You’re breathing hard. Short sentences only. This is the range for "aerobic" capacity. If you're 30 years old, this is roughly 133 to 161 bpm.

The Red Line (Anaerobic)

Above 85%. You’re sprinting. You’re doing hill repeats. You can maybe sustain this for a minute or two before your legs feel like they're filled with lead. This is great for power, but honestly, if you're just exercising for general health, you don't need to live here.

Factors That Mess With Your Numbers

Your heart doesn't live in a vacuum. A "good" pulse rate on a Tuesday might be "dangerous" on a Friday if the conditions change.

- Dehydration: When you're low on fluids, your blood volume drops. Your heart has to beat faster to move that thicker blood around. This is called "cardiac drift." You might be running the same pace as usual, but your heart rate is 15 beats higher because you forgot to drink water.

- Heat and Humidity: This is a big one. If it’s 90 degrees out, your body sends blood to the skin to cool you down. That’s blood that isn't going to your muscles. Your heart rate will skyrocket even if you aren't working harder.

- Caffeine and Meds: That pre-workout powder? It’s basically liquid adrenaline. It’ll spike your pulse. Conversely, beta-blockers (often prescribed for blood pressure) act like a ceiling, making it almost impossible to get your heart rate up, even if you’re working your butt off.

- Stress and Sleep: A bad night's sleep is like adding weight to your invisible backpack. Your heart feels the strain.

The "Talk Test": The Low-Tech Truth

If you hate technology or your chest strap is rubbing you raw, use the talk test. It's surprisingly accurate.

If you can sing "Bohemian Rhapsody" while running, you're in a light-intensity zone.

If you can talk but not sing, you're at a good moderate pulse rate.

If you can only grunt out "water" or "help," you're at high intensity.

Researchers have actually validated this. A study published in the Journal of Sports Sciences showed that the point where speech becomes difficult correlates very closely with the ventilatory threshold—basically the point where your body starts producing more lactic acid than it can clear.

What is a Good Pulse Rate During Exercise for Seniors?

Age changes the plumbing. As we get older, our heart's electrical system changes and the heart wall can become a bit stiffer. For seniors, the goal often shifts from "peak performance" to "safe metabolic health."

The American Heart Association generally suggests that for someone who is 60, a target zone is roughly 80 to 136 bpm. But listen: if you have a history of heart issues, those "standard" numbers go out the window. You need a stress test from a cardiologist. They can tell you exactly where your "ischemic threshold" is—the point where your heart isn't getting enough oxygen. That is the one number you never want to hit.

How to Actually Use This Information

Stop obsessing over the exact beat, but start noticing the trends. If you're 50 years old and your pulse hits 170 while you're just walking briskly, something is up. Either your fitness is very low, or you're over-stressed.

On the flip side, if you're 25 and you can't get your heart rate above 130 while "running," you're probably just strolling.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Workout

First, find your estimated max heart rate. Use the Tanaka formula ($208 - (0.7 \times \text{age})$) because it's just better.

Next, define your goal for the day. If it’s a recovery day, stay under 70%. If it’s a "push" day, aim for that 80-85% sweet spot.

Buy a chest strap if you’re serious. Wrist-based sensors on watches are getting better, but they still struggle with "cadence lock"—where the watch confuses your footfalls for your heartbeat. A chest strap like the Polar H10 or Garmin HRM-Pro reads the electrical signal directly from the heart. It’s the gold standard for a reason.

Finally, watch your recovery heart rate. This is the most underrated metric. One minute after you stop exercising, check your pulse. It should drop by at least 15 to 20 beats. If it drops quickly, your heart is resilient and your nervous system is switching back to "rest and digest" mode efficiently. If it stays high for a long time after you stop moving, you might be pushing too hard or need to focus more on basic cardiovascular base-building.

Exercise is a stressor. The pulse rate is just the dashboard telling you how the engine is handling that stress. Don't let the numbers scare you, let them guide you. If you feel great but the watch says you're high, trust your body—but maybe slow down just a hair to be safe. If you feel like trash but the watch says you're low, go home. Your heart knows things your brain hasn't figured out yet.

Track your resting heart rate every morning for one week to establish a true baseline. Use a chest strap for one high-intensity session to see how it compares to your wrist-based monitor. Adjust your training zones based on the Tanaka formula rather than the 220-age shortcut.