You're sitting in a meeting. Your company needs a new software vendor, and your cousin just happened to launch a tech startup that does exactly what you need. You know he's good. You want him to succeed. But you're also the one signing the contract. That's it. That's the friction.

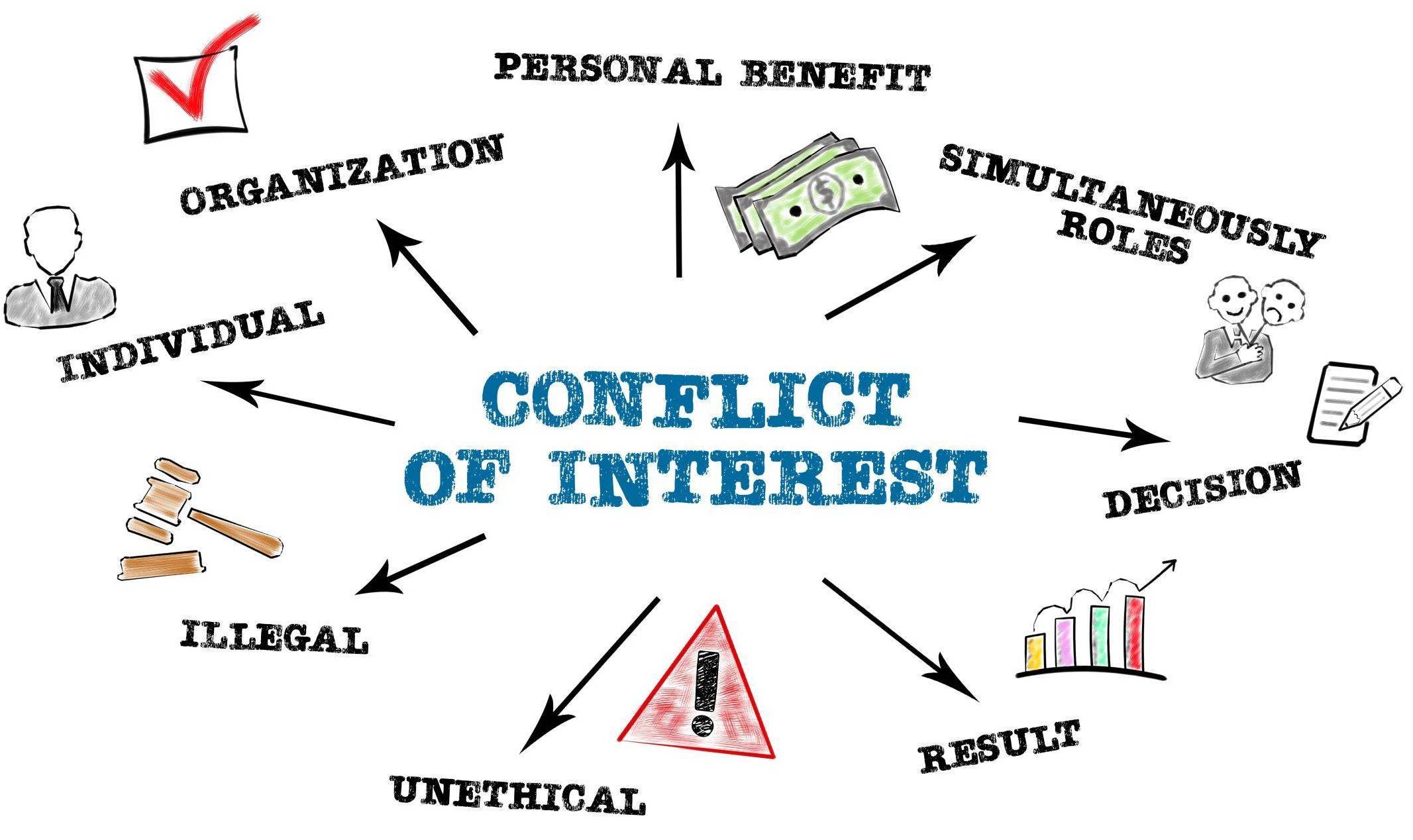

Basically, a conflict of interest happens when your personal loyalties or private interests get in the way of your professional duties. It’s that awkward middle ground where doing what’s best for "you" or "yours" might not be what’s best for the people who pay your salary or trust your judgment. People usually think it involves a suitcase full of cash under a bridge. Honestly? It’s usually much more boring—and much more common—than that.

It isn't always about being "corrupt." You can have a conflict of interest without ever doing anything wrong. The conflict is the situation itself, not necessarily the bad choice that follows.

The Core Concept: Why Neutrality Breaks Down

When we talk about what is a conflict of interest, we are talking about a breakdown in trust. Imagine a doctor who gets a "research grant" from a pharmaceutical company to promote a specific drug. When she writes you a prescription, is she thinking about your health, or is she thinking about that grant? Even if the drug is actually good for you, the relationship with the company creates a shadow of doubt.

This isn't just a corporate thing. It’s everywhere. It shows up in government, in non-profits, and even in your local PTA.

The legal world often looks at this through the lens of "fiduciary duty." That sounds like jargon, but it just means you have a legal or ethical obligation to act in someone else’s best interest. When your own interest starts pulling in the opposite direction, the "fiduciary" part starts to crack.

There are usually three types of these conflicts: actual, perceived, and potential.

An actual conflict is when you’re currently in a position where your personal interest is influencing your work. A potential conflict is when you have an interest that could influence you later. Then there’s the perceived conflict. This one is a nightmare for HR departments. It’s when it looks like you have a conflict, even if you’re being totally honest. In the eyes of the public or your coworkers, perception is often reality. If it looks like you’re biased, the damage to your reputation happens anyway.

Real Examples That Aren't Just Hypotheticals

Let's look at some real-world friction.

🔗 Read more: Enterprise Products Partners Stock Price: Why High Yield Seekers Are Bracing for 2026

Take the case of Enron. It’s the classic example every business student learns. Their CFO, Andrew Fastow, created private companies that did business with Enron. He was basically sitting on both sides of the table—representing Enron and representing his own private entities. That’s a massive, systemic conflict of interest that eventually helped sink the entire company.

In 2018, the health world saw a major stir when the chief medical officer of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Dr. José Baselga, resigned. Why? He hadn't disclosed millions of dollars in payments from drug and health equipment companies in his research papers. It didn't mean his science was definitely wrong. It just meant that nobody could be sure if his findings were objective or bought.

Then there’s the "Revolving Door" in politics. This is a huge talking point in Washington. You have regulators who work for the government, overseeing big banks or tech companies. Then, they quit and take a high-paying job at the very companies they were just regulating. Or vice versa. It makes people wonder: were they being tough on that company, or were they "interviewing" for their next big paycheck while on the taxpayer's dime?

It’s Not Just About Money

We often focus on the "interest" part as being a pile of money. It isn't always.

Sometimes it’s about power. Sometimes it’s about family (nepotism). Sometimes it’s just about ego.

If you're a manager and you're dating someone who reports to you, that’s a conflict of interest. Even if you give them a bad performance review, people will wonder if you were trying to "prove" you weren't biased. If you give them a good review, people will say it’s because you’re dating. You literally cannot win. The relationship itself is the conflict.

The Self-Dealing Trap

Self-dealing is a specific flavor of this. It happens when a person in a position of authority uses their power to steer business toward themselves or their own side businesses.

Think about a city council member who votes to build a new park right next to a plot of land they own. The park might be great for the city. It might be exactly what the neighborhood needs. But because the council member stands to make a killing when their property value spikes, they shouldn't be the one voting on it.

💡 You might also like: Dollar Against Saudi Riyal: Why the 3.75 Peg Refuses to Break

Gift-Giving and the "Grey Area"

This is where most people get tripped up. Is a $20 Starbucks card from a vendor a conflict of interest? Probably not. Is a three-day "educational seminar" in Maui a conflict? Yeah, probably.

Most companies have a "de minimis" rule. It’s a fancy way of saying "this is too small to care about." Usually, it’s a dollar amount—like $25 or $50. If the gift is worth more than that, you have to report it or turn it down. The goal is to prevent "soft influence." You might not think a nice dinner will change your mind about a contract, but psychologists have shown that humans have a deep-seated "reciprocity bias." When someone does something nice for us, we feel an subconscious urge to do something nice back.

How Organizations Try to Fix It

You can't eliminate conflicts of interest. Humans have lives, families, and investments. The goal is to manage them.

Most big organizations use a few standard tools:

- Disclosure: This is the big one. If you have a potential conflict, you tell people. You put it on paper. "Hey, my brother-in-law owns the printing shop we are considering." By bringing it into the light, you take away its power to look like a secret scheme later.

- Recusal: This means you step out of the room. If the committee is voting on your brother-in-law’s printing shop, you don't vote. You don't even participate in the discussion.

- Adherence to Codes of Ethics: Most professional bodies (lawyers, doctors, accountants) have very strict rules about this. If a lawyer tries to represent both the plaintiff and the defendant in a lawsuit, they’ll lose their license faster than you can blink.

Why We Struggle to See Our Own Conflicts

Here is the weird part: most of us think we are immune to bias.

Social psychologists call this the "bias blind spot." We are very good at seeing when other people are being influenced by their interests, but we honestly believe we can stay objective. We tell ourselves, "I'm a professional. I can separate my personal feelings from my work."

The data says otherwise. Studies on medical professionals have shown that even small gifts—like pens or pads of paper with a drug's name on it—can subtly shift prescribing patterns. The doctors aren't lying when they say they are trying to be objective; they just don't realize their brain is being nudged.

This is why "perceived conflict" matters so much. If the public loses faith in the neutrality of an institution—whether it's the news, the courts, or a local business—it's incredibly hard to get that trust back. Once people start asking "What's in it for them?" the value of the work drops.

📖 Related: Cox Tech Support Business Needs: What Actually Happens When the Internet Quits

Identifying a Conflict in Your Own Life

If you’re wondering if you’re currently standing in the middle of a conflict of interest, ask yourself a few blunt questions.

First, if this situation was printed on the front page of the local newspaper, would you feel the need to explain yourself or defend your actions? If the answer is yes, you’ve got a conflict.

Second, does your personal gain (money, reputation, family favor) depend on a specific outcome of your professional work?

Third, would a "reasonable person" looking in from the outside think you were being biased?

It's better to over-disclose than to hide it. If you tell your boss about a potential issue early, it’s a "management challenge." If they find out about it later, it’s a "disciplinary issue."

Actionable Steps for Handling Conflicts

If you find yourself in a situation where your interests are crossing paths with your duties, don't panic. It doesn't mean you're a bad person. It just means you need to follow a process.

- Read the Policy: Check your employee handbook. Most companies have a specific section on "Conflicts of Interest" or "Gifts and Gratuities."

- Speak Up Early: The moment you realize there’s a connection between your private life and a work decision, tell your supervisor or HR representative. Do it in writing (email is fine) so there is a record.

- Step Away: Offer to recuse yourself from the specific decision-making process. If you're on a hiring panel and your old college roommate applies, say, "I know this person well, so I'm going to sit this one out to keep the process fair."

- Document Everything: If you are allowed to continue working on a project despite a disclosed conflict, keep meticulous notes on why certain decisions were made. Transparency is your best defense.

- Ask for an Outside Opinion: If you aren't sure if something counts as a conflict, ask a mentor or a legal professional who isn't involved in the situation. They can often see the "perception" issue that you might be blind to.

Managing these situations isn't about being perfect; it’s about being honest. The goal is to protect the integrity of the work and the trust of the people you serve. When in doubt, lean toward transparency. It's much cheaper than a damaged reputation.