You’re sitting on your porch in upstate New York, maybe sipping some coffee, and suddenly a layer of fine, grey dust settles over everything. Your windows rattle. The ground shakes because of blasting at the nearby quarry. This wasn't a one-time thing for Oscar Boomer and his neighbors in the 1960s; it was daily life next to the Atlantic Cement Company plant in Albany County.

They did what anyone would do. They sued.

But what happened next changed the DNA of American property law and environmental regulation forever. Most people think if someone is polluting your land, you just make them stop. Boomer v. Atlantic Cement Co. proved that in the eyes of the law, sometimes a paycheck is "good enough," even if the smoke never clears.

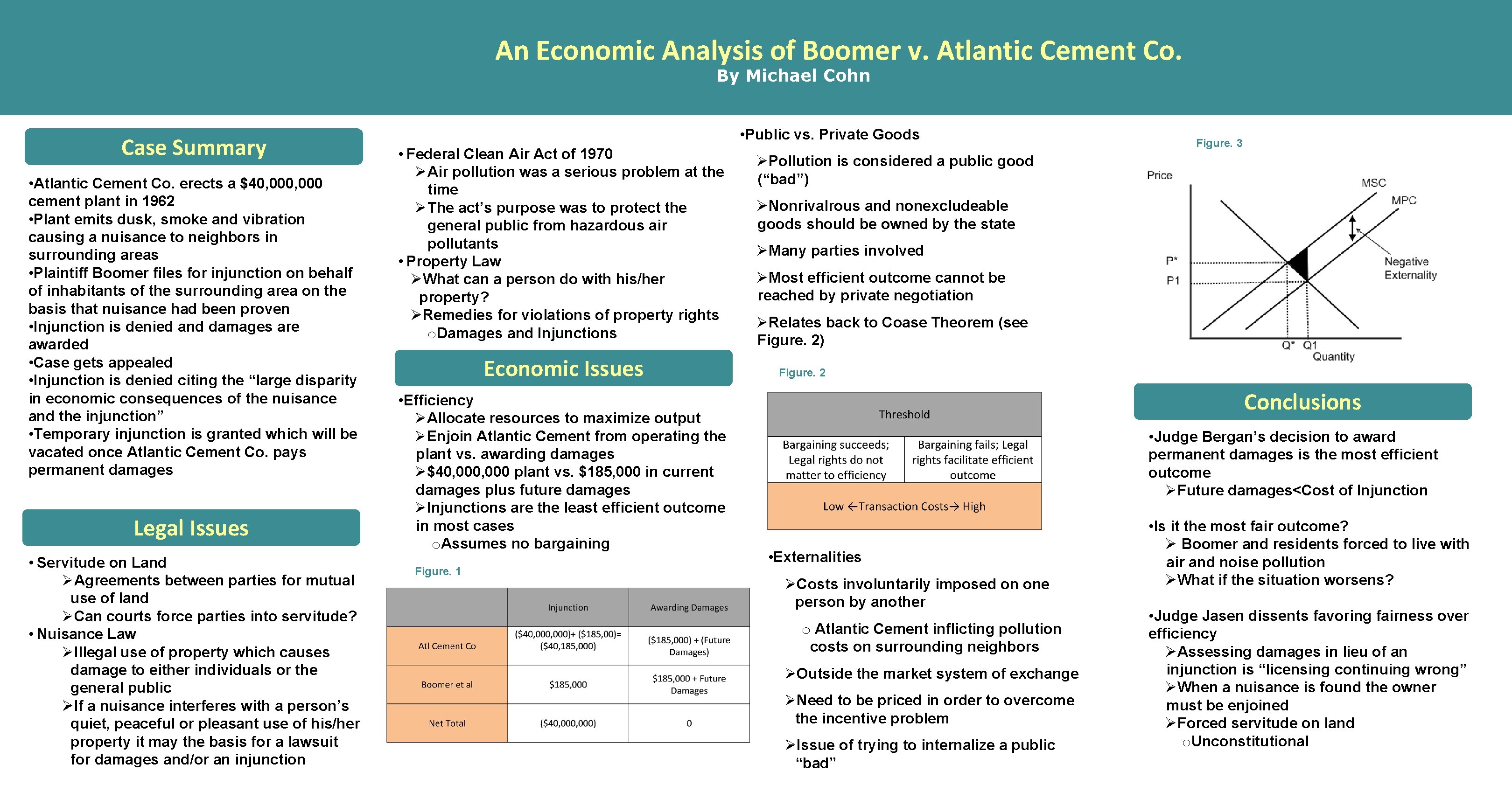

The Massive Mismatch: $45 Million vs. $185,000

To understand why this case is such a big deal, you have to look at the sheer scale of the conflict. On one side, you had a group of eight property owners. Their total permanent damages—the actual loss in their property value—was pegged at about $185,000.

On the other side stood the Atlantic Cement Company.

They had built a state-of-the-art, $45 million facility.

They employed over 300 people.

They were a massive part of the local tax base.

Before this case, New York followed a very strict rule: if a nuisance was "substantial," the court had to issue an injunction. An injunction is a legal "stop" sign. It would have meant shutting down a $45 million plant because of $185,000 in damage.

The court looked at that math and blinked.

💡 You might also like: Why the Old Spice Deodorant Advert Still Wins Over a Decade Later

Why the Court Broke the Rules

Honestly, the New York Court of Appeals was in a tight spot. If they followed the old precedent (set by cases like Whalen v. Union Bag & Paper Co.), they’d have to close the plant. Instead, they decided to do something pretty controversial. They granted a "conditional injunction."

Basically, the court told Atlantic Cement: "We’re ordering you to shut down... unless you pay these neighbors for all the past and future damage you’re ever going to cause them."

Once the company paid that lump sum, the "stop" order would be lifted. Permanently.

This shifted the whole vibe of nuisance law. It turned a property right—the right to not have dust dumped on your head—into a liability rule. You've basically got a situation where the court allowed a private company to "buy" the right to keep polluting.

The "Servitude on Land" Problem

The court called this payment a "servitude on the land." That sounds like fancy legal jargon, but here’s what it means in plain English: the right to pollute stayed with the land. If Oscar Boomer sold his house the next year, the new owner couldn't sue Atlantic Cement again. The "damage" had already been bought and paid for.

What Most People Get Wrong About Boomer

A lot of law students—and even some lawyers—think this case was a win for the environment because it acknowledged the pollution was a nuisance.

📖 Related: Palantir Alex Karp Stock Sale: Why the CEO is Actually Selling Now

It really wasn't.

It was a win for economic efficiency. The court openly admitted they weren't the right people to solve the "public" problem of air pollution. They argued that trying to fix the world's smog problems through private lawsuits was like trying to fix a leaky dam with a Band-Aid.

The Dissent That Predicted the Future

Judge Jasen was the lone voice of dissent, and he was pretty salty about the decision. He argued that the court was essentially granting Atlantic Cement the power of eminent domain—the power to take private property for public use—except this was for a private company’s profit.

He also pointed out a huge flaw: once the company paid the damages, they had zero incentive to ever fix the dust problem. Why spend millions on new filters if you’ve already paid for the right to be messy?

The Legacy: Law and Economics

This case is the poster child for the "Law and Economics" movement. It asks a cold, hard question: what is the most "efficient" outcome for society?

- Option A: Shut down the plant, lose 300 jobs, and lose $45 million in investment.

- Option B: Let the plant run, but make it pay the neighbors for their trouble.

The court chose Option B. This paved the way for modern environmental regulations where we often "price" pollution (like carbon credits) rather than just banning it outright.

👉 See also: USD to UZS Rate Today: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Insights: What This Means for You Today

If you're dealing with a "nuisance" today—whether it's a noisy Bitcoin mine next door or a factory blowing smoke—the ghost of the Boomer case is still hovering over the courtroom.

1. Documentation is everything.

The Boomer plaintiffs won because they could prove "substantial" damage. If you're facing a nuisance, keep a log. Take photos. Get air quality sensors. The law doesn't care about "kinda annoying"; it cares about "economically significant."

2. The "Balance of Equities" is real.

Courts almost always look at the economic impact. If your lawsuit threatens a major employer, don't expect a judge to shut them down on day one. They are much more likely to look for a "money solution" like the court did in 1970.

3. Understand the "Coming to the Nuisance" trap.

One thing that didn't sink the Boomer plaintiffs was the timing. But today, if you buy a house next to an existing cement plant and then complain about the dust, many courts will tell you that you "assumed the risk." Check the local zoning and industrial history before you sign a mortgage.

4. Permanent damages are a one-time deal.

If you ever settle a nuisance claim for "permanent damages," remember that you are likely devaluing your property for the next person who buys it. You are selling a piece of your property's future.

The Atlantic Cement plant (now owned by different entities over the years) is still there. The dust eventually got better because of federal laws like the Clean Air Act, not because of this specific lawsuit. It turns out, while the courts were busy balancing checkbooks, it took the government to actually clean the air.

To see how modern regulations handle these issues, you should look into the EPA's National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), which essentially took the job the Boomer court refused to do. Over time, these standards forced the technical innovations that Judge Jasen feared would never happen.