You're standing on a street corner in Makati, staring at a sky that looks like bruised velvet. Your phone says it's 0% chance of rain. Suddenly, the heavens open up. In seconds, you're soaked. You check the app again. Still 0%. If you've lived through a monsoon season in Manila or a typhoon in Samar, you know this frustration. It's not that the satellites are blind. It's because weather radar in Philippines is a massive, complex, and sometimes broken puzzle that most people don't actually understand.

Weather forecasting here isn't just about looking at clouds from space. Satellites are great for seeing the big picture, like a 500-kilometer wide typhoon spinning in the Pacific. But for the "where should I park so my car doesn't float" kind of detail, you need ground-based radar.

The Doppler Reality Check

PAGASA (the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration) operates a network of Doppler radars across the archipelago. We're talking about massive domes sitting on hillsides from Aparri down to Zamboanga. These things work by shooting microwave pulses into the atmosphere. When those pulses hit a raindrop, they bounce back. By measuring the "shift" in that frequency—the Doppler effect—meteorologists can tell not just where the rain is, but how fast it’s moving and whether it’s rotating. This is literally the difference between "it might rain" and "get to high ground because a tornado-like wind is forming."

But here is the kicker.

The Philippines is a geographical nightmare for radar. We have over 7,000 islands and a spine of mountains (the Sierra Madre and the Cordilleras) that act like giant walls. If a radar station is sitting on one side of a mountain, it can't see what's happening on the other. This is called "beam blockage." It’s why you might see a clear radar sweep for your area while you're actually standing in a downpour. The radar is literally looking over the top of the storm or hitting a mountain instead of the rain.

💡 You might also like: When Was the Clock Invented? The Messy Truth About How We Started Telling Time

Why the Tech Often "Fails" Us

Ever noticed the PAGASA website shows a radar "under maintenance" right when a tropical depression is hovering? It's easy to get angry. Honestly, it’s frustrating. But the hardware is incredibly sensitive. These stations—like the ones in Hinatuan or Guiuan—are often the first things hit by 250 km/h winds. When Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) made landfall in 2013, it essentially vaporized the radar equipment in its path.

Maintaining weather radar in Philippines isn't just a software update. It’s about sending technicians to remote, rugged peaks to fix hardware that has been hammered by salt air, humidity, and extreme heat.

The network currently consists of about 18 to 20 operational stations, depending on the month. Some use C-band, which is good for long-range, and others use S-band, which is better at "seeing" through heavy rain without the signal getting absorbed. If you're looking at a weather map and see huge gaps, it's usually because a station is being calibrated or it's waiting for a part that has to be shipped from abroad. It's a constant battle against the elements.

Reading the Map Like a Pro

Most people look at a radar image and just see "red means bad." That’s a start, but it's localized. You have to look at the "reflectivity" scale, measured in dBZ.

- 20 dBZ: Light mist. You probably won't even need an umbrella.

- 35-40 dBZ: Proper rain. This is where the gutters start to fill.

- 50+ dBZ: Intense rainfall, likely with hail or extreme wind. If you see a "hook" shape in these colors, that's a sign of rotation.

Don't just look at the colors. Look at the animation. If the blobs of rain are growing in size while staying in the same place, that's "stationary" rainfall. That's the stuff that causes the flash floods in places like Marikina or Cebu City. If the blobs are moving fast, the rain will be heavy but short-lived.

The Mystery of the "Clear" Sky

Sometimes you'll see "clutter" on the radar. This is when the beam bounces off buildings, birds, or even swarms of insects. This is why sometimes the PAGASA Twitter (X) feed will show a "cleaner" version of the radar than the raw data you find on third-party apps. Meteorologists use algorithms to filter out the noise. If you're using a generic global weather app, it might not be using those local filters, leading to "ghost rain" on your screen.

The Future: Better Than It Used to Be?

We’ve actually come a long way. Ten years ago, the radar coverage was spotty at best. Today, through partnerships with JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) and massive government investment, the coverage is much more "seamless."

We are seeing the rollout of X-band radars in urban areas. These are smaller, short-range radars that fill in the "blind spots" left by the big Doppler stations. They are perfect for catching those sudden, violent afternoon thunderstorms in Metro Manila that seemingly come out of nowhere.

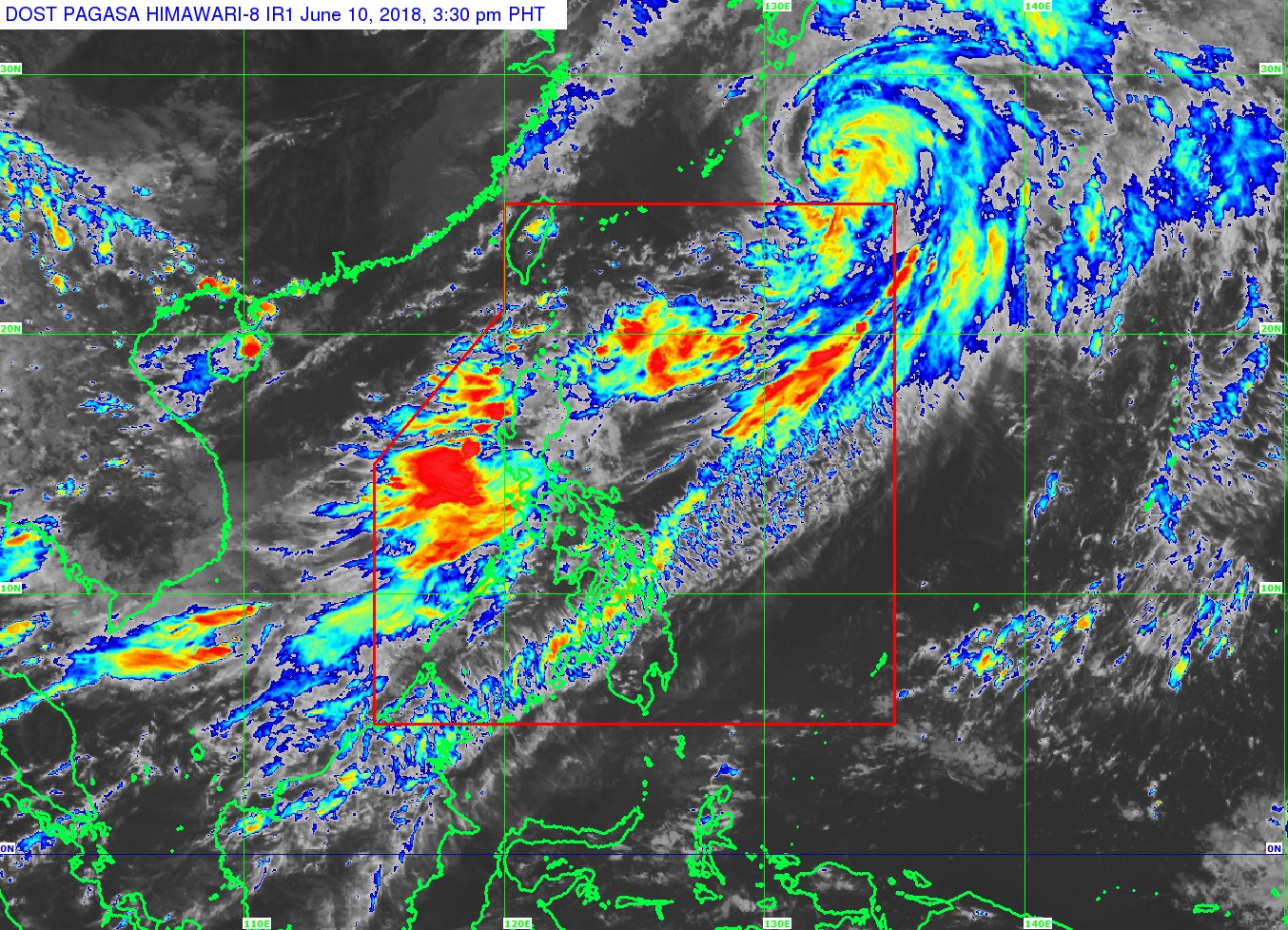

There's also the integration of Himawari-8 and Himawari-9 satellite data. This doesn't replace radar, but it acts as the scout. The satellite sees the storm coming from 36,000 kilometers up, and the weather radar in Philippines catches the "last mile" details as it hits the coast.

Actionable Steps for Staying Dry (and Safe)

Forget just checking the "rain percentage" on your default phone app. It’s often based on global models that don't understand Philippine topography.

- Use the PAGASA "Panahon" Website directly. Look for the "Operational Information" tab. It tells you which radars are actually working. If the Subic radar is down, don't trust the map for Zambales or Bataan.

- Download the RainCheckPH or Windy.com apps. Windy allows you to toggle between different radar sources. Compare the "ECMWF" model with the "GFS" model. If they both agree rain is coming, it’s 99% happening.

- Watch the "Loop" for 30 minutes. Don't just look at a static image. The direction of the "echoes" tells you exactly which neighborhood is next.

- Learn your local "Blockage." If you live in a valley, accept that your local radar might not see anything below 2,000 feet. Use your eyes. If the clouds are "low and fast," the radar is probably missing the bottom half of that storm.

- Check the "Nowcasting" alerts. PAGASA issues these specifically for thunderstorms. These are much more accurate than the 24-hour forecast because they are based on live radar movement.

The tech is getting better, but the Philippine atmosphere is chaotic. No matter how many S-band Doppler stations we build, the mountains will always hide a few secrets. Use the tools, but always keep one eye on the actual horizon.

Next Steps for Disaster Preparedness

Check the PAGASA radar map right now and identify the station closest to your province. Bookmark the direct link to that specific station's feed. In the event of a power outage or slow internet, having the direct link saved can save you minutes of loading time when you need to see if a flood-causing cell is heading your way. If the closest station is "Offline," find the next nearest one and learn to account for the "blind spot" created by the distance. Use this data in conjunction with the Project NOAH (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards) maps to see if your specific street is prone to the rainfall levels being shown on the radar. Awareness of your "radar environment" is the first step in avoiding the next big flood surprise.