You’re standing in front of an electrical panel or a server rack with a digital multimeter in hand. You touch one probe to the neutral wire and the other to the ground. You expect to see zero. Instead, the screen flickers and settles on 2.5V, 5V, or maybe even a startling 15V.

It feels wrong.

💡 You might also like: Why Jensen Huang Still Matters: More Than Just the Man in the Black Leather Jacket

In a perfect world—the one they draw in textbooks—neutral and earth are the same thing. They’re bonded together at the main service entrance. So, mathematically, the potential difference should be non-existent. But the real world is messy. Physics is messy. Neutral to earthing voltage is one of those pesky "real-world" metrics that tells you more about the health of your building’s electrical system than almost any other single reading.

Honestly, most people ignore it until the equipment starts acting up. You’ll see "ghost" resets on PLC controllers, or perhaps a sensitive medical imaging machine starts producing grainy results. Maybe your IT guy is complaining about "noisy" data lines. Most of the time, the culprit isn't a massive surge; it’s just this persistent, low-level voltage hanging around where it shouldn't be.

What’s actually happening in the wires?

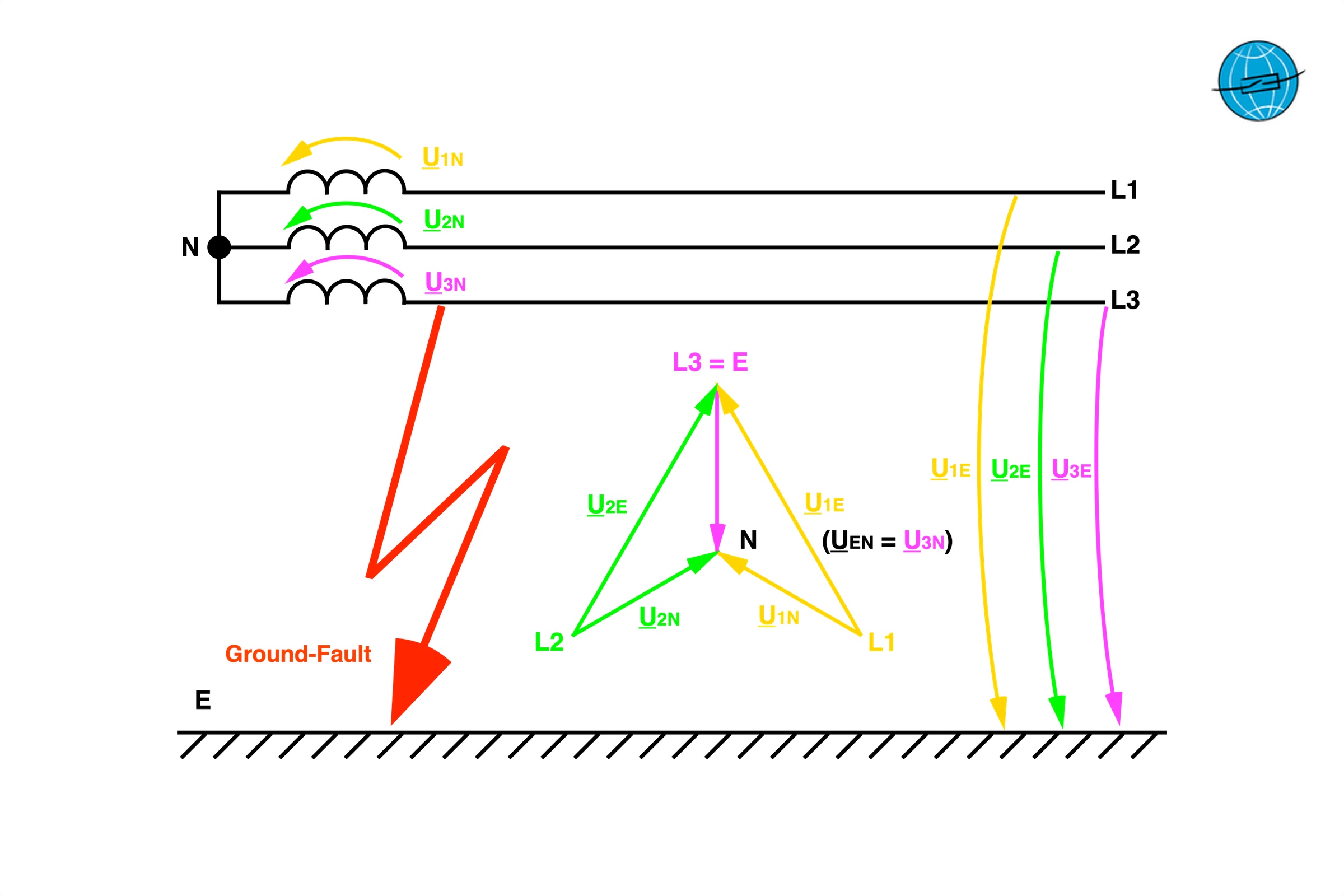

To understand why this voltage exists, we have to look at what the neutral wire actually does. The hot wire carries the current to the load. The neutral wire carries it back.

Earth, on the other hand, is the safety valve. It isn't supposed to carry current at all unless something has gone horribly wrong.

Because the neutral wire has resistance (every wire does, unless you're working with superconductors at liquid nitrogen temperatures), the current flowing through it creates a voltage drop. This is basic Ohm’s Law. If you have a long run of wire and a heavy load at the end of it, that neutral wire is going to "lift" above ground potential.

Think of it like a crowded hallway. If everyone is trying to walk back through the neutral hallway at once, there’s going to be some pressure. The earth hallway is empty. The "voltage" you’re measuring is just the difference in pressure between that crowded neutral path and the empty earth path.

How much voltage is too much?

This is where things get controversial. If you ask ten different electrical engineers, you might get twelve different answers.

The IEEE 1100 (often called the Emerald Book) used to suggest that 0.25V or less was the gold standard for sensitive electronic sites. That’s incredibly low. In a modern industrial setting, that’s almost impossible to achieve. Most experts today, including those following National Electrical Code (NEC) guidelines in the US, generally accept that under 2V at the outlet is healthy.

If you see 2V to 5V, it’s a gray area. It might be fine for a toaster, but it could make a high-end audio interface buzz like a beehive.

📖 Related: How to connect laptop and tv with hdmi cable: The Simple Fix for Most Setup Issues

Once you cross the 5V threshold? You’ve got problems.

At 15V or 30V, you aren't just looking at "noise" anymore. You’re looking at a potential safety hazard or a serious system fault. High neutral-to-earth voltage is frequently a symptom of an overloaded neutral, a loose connection, or—heaven forbid—a shared neutral between two different circuits that shouldn't be talking to each other.

The hidden danger of "Shared Neutrals"

Residential wiring often uses something called a Multi-Wire Branch Circuit (MWBC). Basically, two "hot" wires share one neutral. It’s an efficient way to save copper. But if those two hots are on the same phase instead of opposite phases, the current on the neutral doesn't cancel out. It doubles.

When that happens, the neutral gets hot. Not just electrically hot, but physically hot. The insulation can melt. Long before the fire starts, you’ll see your neutral to earthing voltage spike because the wire's resistance is through the roof.

I’ve seen offices where printers would reboot every time the air conditioner kicked on. Everyone blamed the power grid. It turned out to be a loose lug on the neutral bar in the sub-panel. A half-turn with a screwdriver dropped the neutral-to-earth voltage from 12V down to 1.2V, and the "haunted" printers suddenly started working perfectly.

Harmonics: The silent voltage booster

We can't talk about modern electricity without talking about Switched Mode Power Supplies (SMPS). These are in everything—your laptop charger, your LED lights, your TV.

Unlike an old-school lightbulb, these devices don't draw current in a smooth wave. They gulp it in quick, jagged bursts. These "nonlinear loads" create harmonics, specifically the 3rd harmonic ($180Hz$ in a $60Hz$ system).

💡 You might also like: Dyson Hair Dryer and Diffuser: What Most People Get Wrong

Harmonics are the ultimate party crashers. In a three-phase system, the normal $60Hz$ current usually cancels out on the neutral. But 3rd harmonics are "additive." They don't cancel; they pile up. You can end up with more current on the neutral wire than on the hot wires. This is a recipe for massive neutral-to-earth voltage readings and, eventually, a very expensive smell of burning electronics.

Measuring it correctly (Don't be fooled by "Ghost" Voltage)

You can't just jab a cheap meter into an outlet and trust the first number you see. High-impedance multimeters are so sensitive they can pick up "ghost voltage" or electromagnetic induction from nearby wires.

If you’re serious about diagnosing this, you need a meter with a "Low Z" (low impedance) mode. This puts a tiny load on the circuit, dissipating the stray induction so you see the real potential difference.

- Set your meter to AC Volts.

- Place the black probe in the ground slot (the round or U-shaped one).

- Place the red probe in the neutral slot (the wider vertical slot in the US).

- Observe the reading under load. Turn on the equipment that usually runs on that circuit. If the voltage jumps significantly when the machine starts, you have a high-resistance neutral.

How to fix high neutral to earthing voltage

If your readings are consistently above 2V-3V, you need to act. It isn't just about protecting your gear; it's about efficiency.

- Check the Bonds: Ensure the neutral-to-ground bond only exists at your main service entrance or at a "separately derived source" like a transformer. If someone bonded them again at a sub-panel (a common DIY mistake), you’ve created a parallel path for return current. This is dangerous and causes huge voltage swings.

- Tighten the Lugs: Electricity involves vibration. Over years, those screws in the breaker panel can back off. A loose neutral is a high-resistance neutral.

- Upsize the Neutral: In data centers or buildings with heavy LED lighting, engineers often double the size of the neutral wire to handle the harmonic load.

- Dedicated Circuits: For the really sensitive stuff—like a recording studio or a lab—run a dedicated circuit with its own insulated ground and its own neutral. Don't let the breakroom microwave share a return path with your $50,000 server.

Real-world nuance: The "0.0V" Trap

Interestingly, seeing exactly $0.000V$ can actually be a bad sign. It often means the neutral and ground are shorted together somewhere near the outlet. While that sounds "safe," it actually means your ground wire is now carrying return current, which it is never designed to do. You want to see a tiny bit of voltage—maybe $0.2V$ to $1.5V$. That indicates the two systems are distinct and functioning as intended.

Your Action Plan for Today

If you suspect your electrical "noise" is actually a voltage issue, start with a baseline.

First, measure the voltage at the outlet with nothing plugged in. Then, plug in a heavy load—like a space heater or a large laser printer—on the same circuit and measure again. A jump of more than 1 or 2 volts indicates that the wiring gauge might be too thin for the length of the run, or there's a failing connection somewhere in the walls.

Second, check your sub-panels. Make sure the green (ground) and white (neutral) wires are on completely separate bus bars and that those bars aren't touching.

Lastly, if you're consistently seeing over 5V and your connections are tight, call an electrician with a power quality analyzer. It's likely a harmonic issue or a problem with the utility's transformer outside. Catching it now is a lot cheaper than replacing a fried motherboard next month.

Understanding neutral to earthing voltage isn't just for electrical engineers. It's for anyone who wants their technology to last longer and run quieter. Keep those levels low, keep your connections tight, and stop letting your neutral wire act like a second hot.