Let’s be honest. Most people hear the phrase "in-kind income" and their eyes glaze over instantly. It sounds like something a tax lawyer would mumble while staring at a spreadsheet in a basement. But if you’re running a non-profit, managing a small business, or even just trying to stay on the right side of the IRS, it’s actually a huge deal. Basically, it’s the stuff you get for free—or at a deep discount—that usually has a real-world price tag attached.

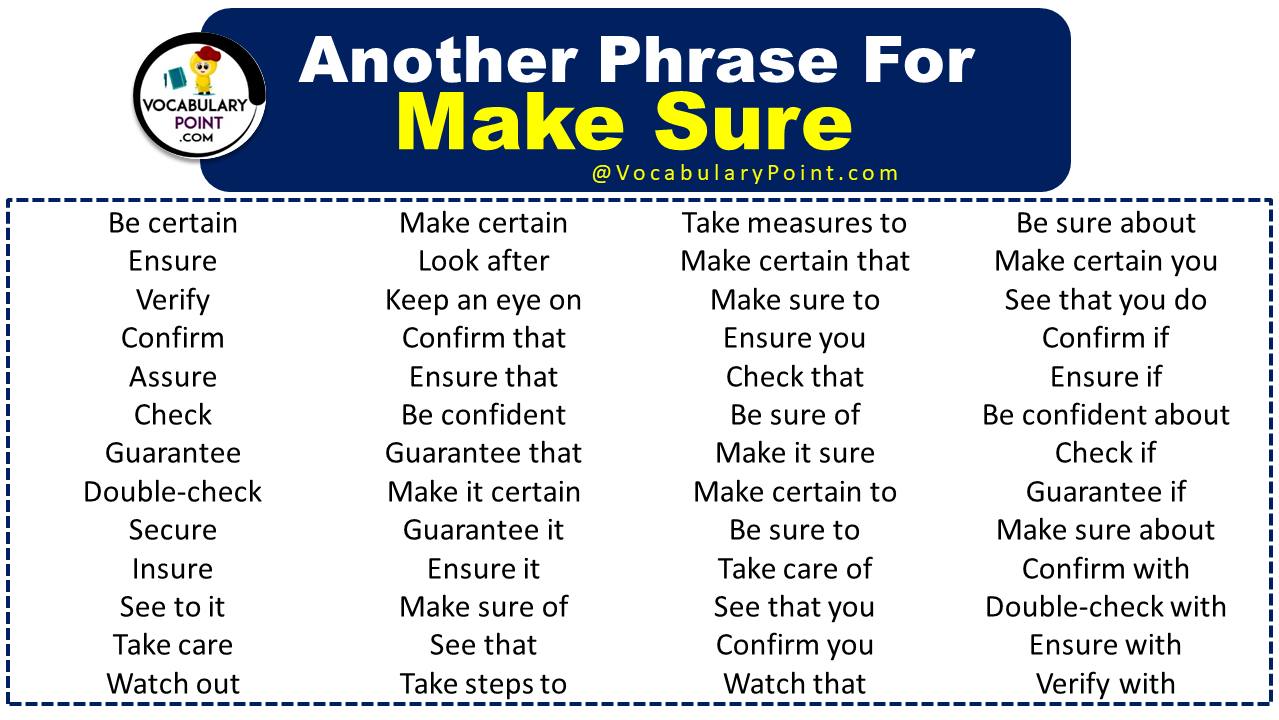

We’re talking about things like a free office space, donated professional legal services, or even that pile of high-end laptops a local tech firm handed over because they were upgrading. Because we want to make sure we have all in-kind income documented, we have to look past the cash register. If you ignore it, your financial health looks weaker than it actually is. Or worse, the IRS decides you’re hiding things.

What is In-Kind Income Anyway?

Think of it as "payment in stuff." Instead of writing you a check for $5,000, a donor gives you $5,000 worth of printing services for your annual gala. In the eyes of the accounting world, that’s still $5,000. It counts. It matters.

According to the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), specifically under ASC 958-605, non-profits have to recognize contributed services if they create or enhance non-financial assets or require specialized skills. If a plumber fixes your sink for free, that’s in-kind income. If a volunteer just stands at a door and waves at people, that’s great, but it usually doesn’t count as a reportable financial transaction because it doesn't require a "specialized skill" in the technical sense. It's a weird distinction, right? But that’s the law.

The Value Gap

Here is where it gets tricky. How do you value a used van? Or a stack of slightly out-of-date textbooks? You can't just guess. You need "Fair Market Value" (FMV). This isn't what you wish it was worth. It’s what a random person would actually pay for it on the open market today.

People mess this up constantly. They overvalue things to make their organization look bigger, or they undervalue them to avoid paperwork. Both are bad ideas. Honestly, the IRS is way more interested in consistency than perfection, but you have to show your work.

✨ Don't miss: 40 Quid to Dollars: Why You Always Get Less Than the Google Rate

Why We Want to Make Sure We Have All In-Kind Income Tracked

It’s about the narrative.

If your non-profit brings in $100,000 in cash but receives $200,000 in free rent and pro-bono consulting, your "true" operating budget is $300,000. If you only report the cash, you look like a tiny operation struggling to survive. When you record that in-kind support, you suddenly look like a robust organization with deep community ties. Grant makers love that. They want to see that other people are investing in you, even if that investment isn't coming in a green, paper format.

Also, transparency.

If you’re a 501(c)(3), you’re filing Form 990. The IRS wants to see those non-cash contributions on Schedule M. If you suddenly show up with a brand new building but your bank account didn't change, they’re going to have questions. Questions lead to audits. Audits lead to headaches that no amount of free coffee—another form of in-kind income, by the way—can fix.

The Specialized Skills Rule

Let’s talk about the "Professional Rule" for a second. This is a common trip-wire.

🔗 Read more: 25 Pounds in USD: What You’re Actually Paying After the Hidden Fees

- Specialized Skills: If a lawyer gives you legal advice, record it.

- Enhancing Assets: If a construction company builds a deck on your community center, record it.

- General Labor: If 50 college students show up to pick up trash, you usually don't record that as income on your financial statements (though you can track it for "volunteer hours" in your annual report).

It feels unfair, doesn't it? The trash-picking is vital! But the accounting rules are rigid. They care about "marketable" skills.

The Paper Trail: Don’t Just Wing It

You need a receipt for everything. Even the free stuff.

When someone gives you an in-kind gift, you should issue an acknowledgment letter. It shouldn't list the dollar value—that’s actually the donor’s job to determine for their own taxes—but it should describe what was given. "One pallet of Grade A printer paper" or "10 hours of architectural consulting."

Inside your own books, though, you do need that dollar amount. We want to make sure we have all in-kind income reflected in the general ledger. You’ll usually see this as a "wash" on the P&L: you record the Income (In-kind Contribution) and then a corresponding Expense (Professional Services or Supplies). It nets to zero on your bottom line, but it inflates your total revenue and total expenses to reflect reality.

Real World Example: The Tech Startup

Imagine a small tech incubator. A local law firm offers them "free" space in their building. The market rate for that office is $3,000 a month. Over a year, that’s $36,000.

💡 You might also like: 156 Canadian to US Dollars: Why the Rate is Shifting Right Now

If the incubator doesn't track that, their books show $0 rent. That looks great until the law firm decides they need the space back. Suddenly, the incubator's expenses jump by $36,000 overnight. By tracking the in-kind income from day one, the board of directors understands the true cost of running the business. They aren't blindsided when the "free" ride ends.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Don't be the person who records a donation of 500 old t-shirts as if they were brand new Designer gear. It’s tempting. It makes the numbers look big. But "Fair Market Value" is the law of the land. If you could buy it at a thrift store for $2, you record it at $2.

Another big one? Not tracking the time.

If an IT expert spends her Saturday setting up your server, that’s a specialized skill. If she spends her Saturday painting a wall, that’s technically not a specialized skill (unless she’s a professional painter). It sounds pedantic, but these are the distinctions that keep your 990 clean.

Actionable Steps for Clean Books

Getting your in-kind income sorted doesn't require a PhD in accounting, just a bit of discipline.

- Create a specific "In-Kind" account in your Chart of Accounts. Don't let it mingle with your cash donations. It needs its own line item so you can see it clearly at a glance.

- Draft an In-Kind Gift Policy. This is a simple document that tells your staff what you accept and how you value it. It stops people from accepting "donations" that are actually just someone else's trash.

- Use a standard valuation form. Every time a non-cash gift comes in, have the person who received it fill out a quick form describing the item, its condition, and the source of the valuation (like a link to a similar product online).

- Review your volunteer logs. Once a quarter, look at who gave their time. Identify the "specialized" hours (accounting, legal, medical, trades) and get those into the system.

- Talk to your auditor early. If you’re getting an annual audit, don’t surprise them with a pile of in-kind receipts in December. Ask them in June how they want the documentation formatted.

Tracking these contributions isn't just about following rules; it's about respecting the generosity of your community. When you record that $500 donation of supplies, you're acknowledging that someone gave you $500 worth of value. It matters for your taxes, it matters for your growth, and honestly, it just makes for better business.

The goal is a financial statement that actually tells the truth. Cash is only half the story. The rest is in the services, the goods, and the space that people provide to keep your mission moving forward. Keep the records tight, stay consistent with your valuations, and you'll find that your organization is likely much "wealthier" than your bank balance suggests.