You've probably stared at a company’s balance sheet and felt that slight pang of confusion when you hit the bottom line. It’s okay. Most people do. We talk about revenue and profit all day long, but stockholders equity is the real heart of the operation. It is what’s left when the music stops.

Basically, if a company decided to close its doors today, paid off every single debt it owed to the bank, the suppliers, and the taxman, stockholders equity is the pile of cash left on the table for the owners. It’s the "net worth" of the business. But it isn't just a static number. It's a living history of every dollar the company ever raised and every cent it ever kept.

What Stockholders Equity Actually Represents

Think of it like home equity. If your house is worth $500,000 and you owe the bank $300,000, you have $200,000 in equity. Simple, right? Businesses work the same way. The formal accounting equation is $Assets - Liabilities = Stockholders Equity$.

But here is where it gets kinda tricky. On a balance sheet, assets are often recorded at "historical cost." That means if a company bought land in 1970 for $50,000, it might still be sitting there at $50,000, even if it’s worth $5 million now. This is why equity on paper—what we call "Book Value"—is rarely the same as what the company is actually worth on the stock market (Market Cap).

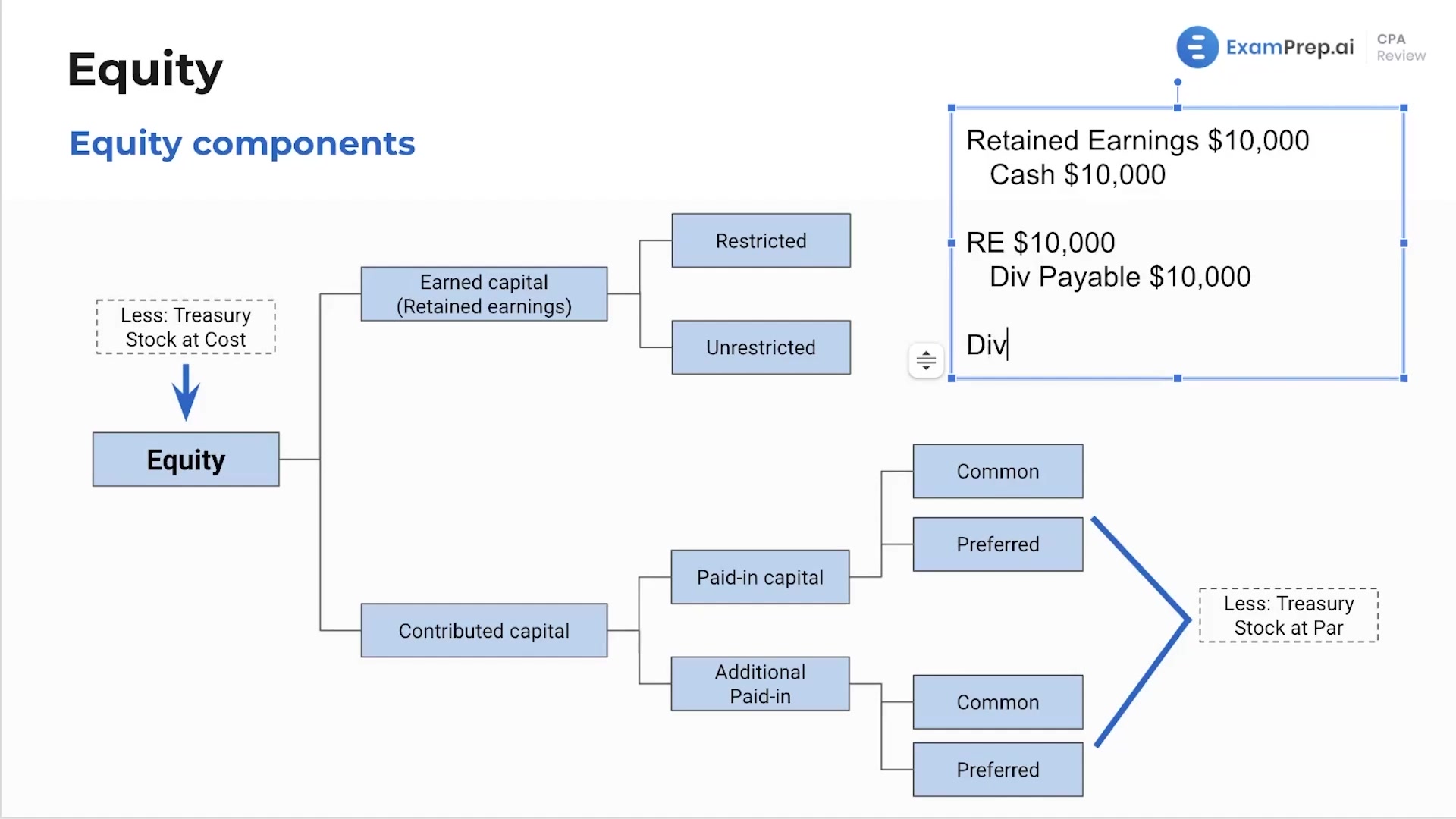

The Ingredients in the Equity Pot

You can't just look at one number. You have to see where it came from. Usually, equity is built from two main sources. First, you have the money investors put in when the company first started or issued new shares. This is Paid-in Capital. It’s the "seed money."

Then, you have the most important part: Retained Earnings.

Retained earnings are the profits the company kept instead of paying out as dividends. If a company has massive retained earnings, it means they are a money-making machine. If that number is negative (often called an "accumulated deficit"), the company has basically been burning furniture to keep the lights on. Look at a company like Amazon in its early years; it had a massive deficit because it was reinvesting every dime into growth. Now? It’s a different story.

Why This Number Can Be Outright Lying to You

Honestly, stockholders equity can be deceptive. A company can have "negative equity" and still be a titan. Take Boeing or McDonald's at various points in recent history. How does that happen? It sounds like they are bankrupt, but they aren't.

Negative equity often happens because of Treasury Stock. This is when a company uses its own cash to buy back its shares from the open market. When they do this, it shrinks the equity side of the balance sheet. If they do it aggressively enough—maybe by taking on debt to fund the buybacks—the equity can actually dip below zero.

It’s a weird accounting quirk. The company is basically betting on itself. While it looks scary on a spreadsheet, investors often love it because it means their individual shares now represent a bigger piece of the remaining pie.

The Role of Preferred vs. Common Stock

Not all equity is created equal. If you own "common stock," you're at the back of the line. If the company goes bust, the "preferred stockholders" get their cut first.

💡 You might also like: WeatherTech Super Bowl Ad 2025: Why Those Biker Grandmas Stole the Show

- Common Stock: You get voting rights and the potential for huge upside.

- Preferred Stock: It’s more like a bond. You get a fixed dividend, but you usually don't get to vote on who the CEO is.

- Additional Paid-In Capital (APIC): This is just the "premium" people paid over the stock's face value. Since most stocks have a "par value" of like $0.01, almost all the money raised from an IPO ends up in the APIC bucket.

How to Use Equity to Spot a Bad Investment

If you want to know if a management team is actually good at their jobs, don't just look at net income. Look at Return on Equity (ROE).

$ROE = \frac{Net Income}{Average Stockholders Equity}$

This tells you how much profit the company generates with the money shareholders have invested. A company that makes $1 million in profit on $10 million in equity (10% ROE) is okay. But a company that makes that same $1 million on only $2 million in equity (50% ROE) is an absolute star. They are efficient. They don't need a massive pile of cash to generate results.

However, be careful. High ROE can be faked with high debt. If a company borrows a billion dollars and uses it to buy back stock, their equity shrinks. Suddenly, their ROE looks huge, but their risk profile just exploded. You've got to look at the debt-to-equity ratio alongside it to get the full picture.

👉 See also: How to Qualify for Unemployment in NY: What Most People Get Wrong

The "Other" Stuff: AOCI

There is a line item called Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI). It sounds like boring accounting jargon because, well, it is. But it matters.

AOCI is where companies hide gains and losses that haven't "happened" yet. Imagine a company owns a bunch of Euro-denominated bonds. If the Euro crashes, the company has lost value, but they haven't sold the bonds yet. That "unrealized" loss sits in AOCI. It’s like a waiting room for financial pain or glory. During the 2023 banking jitters, AOCI was the place where all those "unrealized losses" on Treasury bonds were hiding before they caused trouble for banks like Silicon Valley Bank.

Real World Example: Tech vs. Manufacturing

Let's compare. A company like Intel has massive stockholders equity because they own multi-billion dollar factories (fabs). Their assets are huge.

Now look at a software company. They might have very little "stuff." Their value is in their code and their people, which don't really show up as assets on a balance sheet. Consequently, their stockholders equity might look tiny compared to their market value.

This is why comparing the equity of a steel mill to the equity of a SaaS startup is a waste of time. You have to compare within the same neighborhood.

Common Misconceptions That Cost People Money

A lot of beginner investors think that if they buy a stock below its "Book Value" (Equity per share), they are getting a steal. This is the classic "Value Investing" trap.

Sometimes a stock is cheap because the assets are garbage. If a company has $100 million in equity, but $80 million of that is "Goodwill" (an intangible asset from an old acquisition that didn't pan out), that equity is a ghost. It isn't real. When you analyze stockholders equity, always strip out the "intangibles" to see the Tangible Book Value. That is the cold, hard reality of what the company owns.

Actionable Steps for Your Portfolio

- Check the Retained Earnings Trend: Is it growing every year? If it’s shrinking while management is bragging about "record revenue," something is wrong. They are leaking cash.

- Calculate Tangible Book Value: Subtract Goodwill and Intangible Assets from the total Stockholders Equity. This gives you a "margin of safety" number.

- Watch the Buybacks: If equity is dropping because of share repurchases, check the debt levels. If they are borrowing to buy back shares at an all-time high stock price, they are destroying shareholder value, not creating it.

- Look for Dilution: If the "Common Stock" or "Paid-in Capital" lines are growing fast, the company is printing new shares. This waters down your ownership. It’s like slicing a pizza into 12 pieces instead of 8; you still have the same pizza, but your slice just got smaller.

Stockholders equity isn't just a boring number at the bottom of a filing. It’s the scorecard. It tells you exactly how much value has been created—or destroyed—since the day the company sold its very first share. Stop ignoring it.