Light is weird. Seriously. You point a flashlight at a wall, and it's a circle. You stick a straw in a glass of water, and it looks like it’s snapped in half. But nothing is quite as trippy as looking through a magnifying glass and seeing the world turn upside down. That’s the magic—or rather, the geometry—of a convex lens ray diagram.

Most people think of lenses as just "glass that makes stuff bigger." Honestly, that’s a massive oversimplification. Depending on where you stand, a convex lens can make things look tiny, giant, or vanish into a blurry mess. It’s all about the convergence of light. While a concave lens scatters light like a panicked crowd, a convex lens brings it together, like a magnifying glass focusing sunlight to a single, scorching point.

What Actually Happens Inside the Glass?

A convex lens is thicker in the middle than at the edges. Because of this shape, it’s technically called a converging lens. When parallel rays of light hit that curved surface, they don't just pass through; they bend toward the center. This is refraction.

Think of the "optical center." This is the dead center of the lens. Any light ray passing through this point doesn't bend at all. It just keeps going, straight as an arrow. Then you have the "principal axis," which is the imaginary horizontal line cutting the lens in half. The points where the magic happens are the focal points ($F$). Every lens has two—one on each side. The distance from the center to $F$ is your focal length.

If you’ve ever tried to burn a leaf with a magnifying glass (we’ve all been there), you were literally finding the focal point. You were manipulating a convex lens ray diagram in real-time. You move the lens until the "circle" of light becomes a tiny, intense dot. That dot is the sun’s image being projected exactly at the focal point.

The Six Scenarios That Mess With Your Head

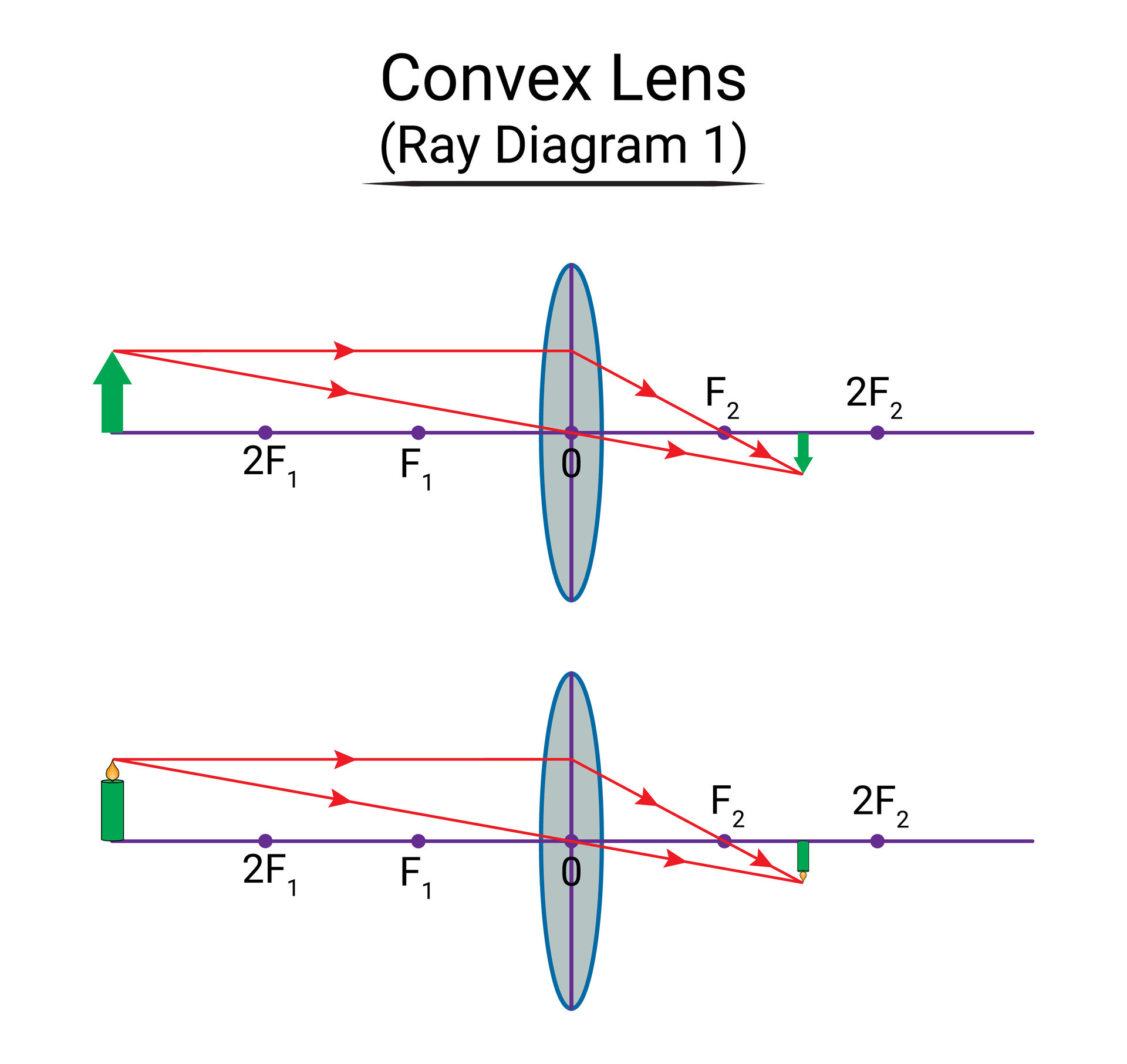

Position matters. It’s the difference between a clear image and a smudge. In physics, we usually track three specific rays to figure out where an image will form. First, a ray parallel to the axis that bends through the far focal point. Second, a ray going straight through the optical center. Third, a ray passing through the near focal point that comes out parallel.

Where these lines cross? That’s your image.

Objects at Infinity

When an object is super far away—like a star or the sun—the rays hit the lens almost perfectly parallel. In this convex lens ray diagram, the rays converge exactly at the focal point ($F$). The image is tiny. It’s real. It’s inverted, though you can’t really tell with a star.

Beyond 2F

Imagine the object is sitting a bit back from the lens, further than twice the focal distance. The image forms on the other side, squeezed between $F$ and $2F$. It’s smaller than the original. If you’re using a camera, this is basically how the lens captures a mountain and fits it onto a tiny sensor.

Sitting Right at 2F

This is the "perfect" spot. If the object is at $2F$, the image shows up at $2F$ on the other side. It’s the exact same size. It’s just upside down. It’s like a geometric mirror image that decided to stand on its head.

Between F and 2F

Now things get big. As the object moves closer to the lens, the image moves further away and grows. In this convex lens ray diagram, the image forms beyond $2F$. It’s magnified. This is the sweet spot for projection. Think of an old-school film projector. The tiny frames of film are placed between $F$ and $2F$ so they appear giant on the theater screen.

✨ Don't miss: Turn My Camera On: Fixing the Glitchy Webcam Issues That Actually Matter

The "Ghost" at F

This is the weirdest part. If you put an object exactly at the focal point, the light rays come out the other side perfectly parallel. They never cross. No image forms. Or, as physicists like to say, the image is at "infinity." It’s just a blur of light.

The Magnifying Glass Effect (Inside F)

If you move the object closer than the focal point, the rays on the other side diverge. They spread out. Your eye traces these spreading rays backward, and you see a "virtual" image. It’s upright. It’s huge. This is why a magnifying glass works. You aren't looking at a real projection; your brain is being tricked by a convex lens ray diagram where the lines only meet in "imaginary" space behind the lens.

Why Should You Care? (Real World Stakes)

This isn't just for passing a high school physics quiz. It’s the foundation of almost all optical technology.

Take the human eye. Your eye has a natural convex lens. When you look at a tree, your lens creates a convex lens ray diagram that projects a real, inverted image onto your retina. Your brain then flips it so you don't spend your life feeling dizzy. When people become farsighted (hyperopia), their eyeball is often too short, or the lens is too flat. The image tries to focus behind the retina. To fix it, doctors put another convex lens in front of the eye (glasses) to bend the light sooner.

Microscopes use a series of these lenses. The "objective" lens creates a magnified real image, and then the "eyepiece" acts as a second magnifying glass to blow that image up even further. We are talking about stacking geometry on top of geometry.

Common Mistakes People Make

Honestly, the biggest mistake is forgetting that "real" images are always upside down. If you see a diagram where the light rays actually cross and the image is right-side up, someone messed up.

Another one? Thinking the lens stops working if you cover half of it. It doesn't. If you block the top half of a convex lens, you still get a full image. The image just gets dimmer because there's less light to work with. The geometry of the convex lens ray diagram remains the same because every single point on the lens contributes to the whole image.

👉 See also: Why the Salem New Hampshire Apple Store is Actually a Massive Regional Hub

Actionable Takeaways for Mastering Optics

If you're trying to draw these or understand them for a project, keep these rules in your back pocket:

- The Straight Shooter: Always draw the ray going through the center first. It’s the easiest because it never bends.

- The Parallel Rule: Any ray entering parallel must exit through the focal point on the other side.

- Real vs. Virtual: If the light rays actually touch, it's a real image you can project on a piece of paper. If you have to "trace back" with dotted lines, it's virtual—it only exists in your head (and the lens).

- Check Your Focal Length: The "power" of a lens is $P = 1/f$. A thicker, more curved lens has a shorter focal length and bends light more aggressively.

To really see this in action, grab a pair of reading glasses (which are convex) and a flashlight in a dark room. Try to project the shape of the flashlight bulb onto a wall by moving the lens back and forth. You’ll see the exact moment the convex lens ray diagram hits the "Real and Inverted" stage. It’s one thing to read about it; it’s another to see a tiny, glowing lightbulb appear upside down on your bedroom wall.