You’re planning a wedding for next October. Or maybe you’re a farmer in Nebraska staring at a dusty field, wondering if the "Big Dry" is finally going to snap. You open a weather app, scroll past the ten-day mark, and see... nothing. Or worse, you see a vague colored map from the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) that looks like a preschooler’s watercolor project.

Predicting the weather for tomorrow is easy. We have satellites for that. But getting a reliable long term temp forecast? That is where the science gets messy, humble, and honestly, a little bit frustrating.

We live in an era of supercomputers that can simulate billions of atmospheric variables in seconds. Yet, if you ask a meteorologist if it’ll be snowing on Christmas six months out, they’ll probably just sigh. It isn’t because they’re lazy. It’s because the atmosphere is a chaotic beast that hates being put in a box.

The 14-Day Wall is Real

Most people don't realize that standard weather models basically go "blind" after about two weeks. This is known in the industry as the limit of predictability. Edward Lorenz, the father of chaos theory, famously talked about the butterfly effect. A flap of a wing in Brazil causes a tornado in Texas. While that’s a bit dramatic, the math holds up. Small errors in today’s data grow exponentially. By day 15, the error is often as large as the signal itself.

So, how do we get a long term temp forecast that actually means something?

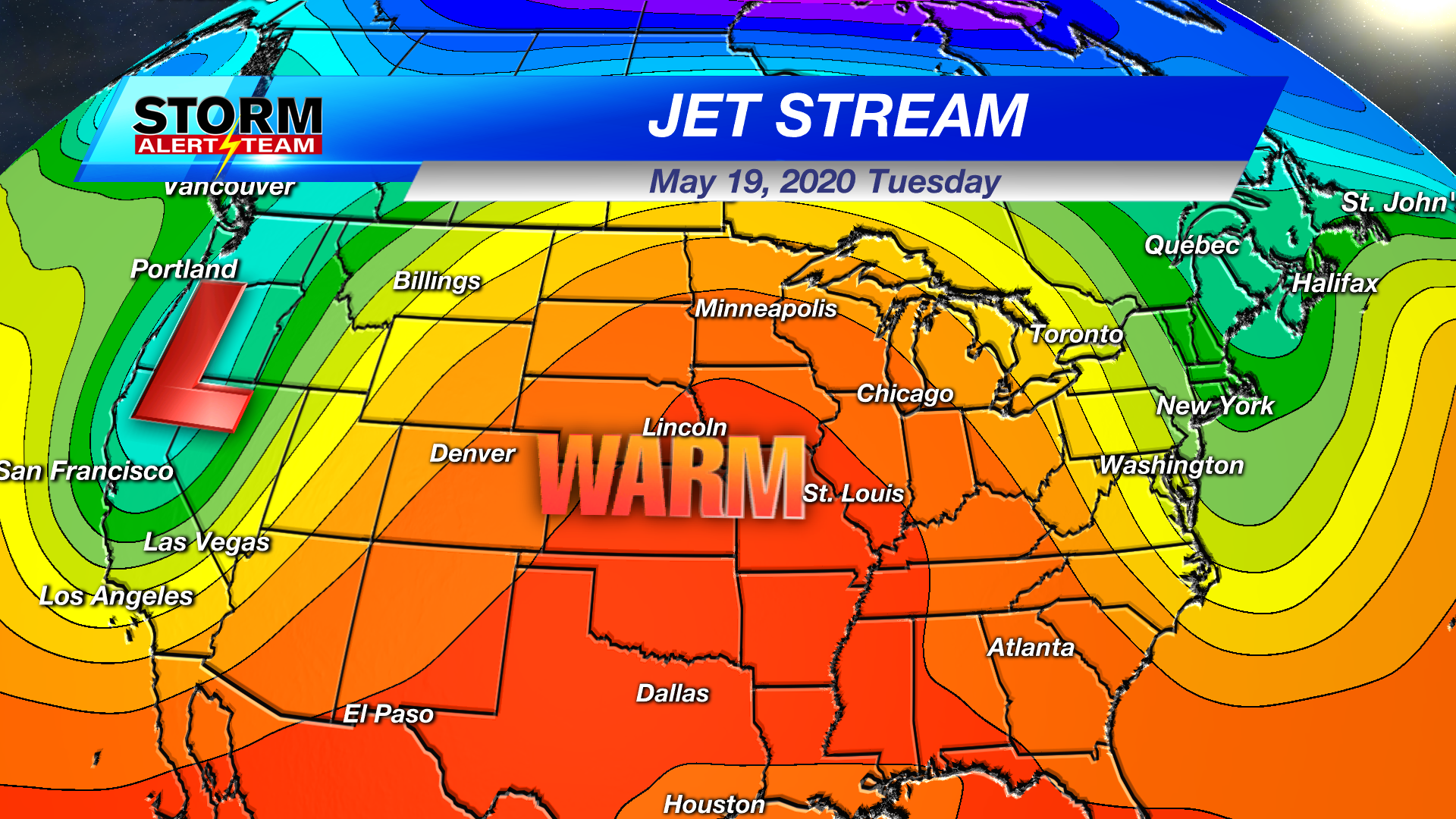

We stop looking at individual storms. We start looking at the "big players." I’m talking about ocean temperatures, massive pressure ridges, and the slow-moving giants of the atmosphere that steer the jet stream.

El Niño and His Moody Sister

If you want to know what the temperature will be like three months from now, you have to look at the water. Specifically, the Pacific Ocean. The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the undisputed king of seasonal forecasting.

When the waters near the equator get unusually warm, we call it El Niño. This shifts the jet stream south. For the United States, this usually means a cooler, wetter southern tier and a much warmer northern tier. On the flip side, La Niña—the cooling phase—often brings blistering cold shots to the northern Plains and Pacific Northwest while leaving the South high and dry.

💡 You might also like: Daniel Blank New Castle PA: The Tragic Story and the Name Confusion

But here’s the kicker: ENSO isn't a perfect script.

Take the winter of 2023-2024. We had a "Super El Niño." On paper, that should have meant a specific pattern for the Northeast. Instead, we saw record-breaking warmth that defied several historical analogs. Why? Because the Atlantic Ocean was also record-breakingly hot. When the Pacific and Atlantic fight, the long term temp forecast becomes a guessing game of which ocean has more "muscle" that week.

The Arctic Oscillation: The Wild Card

Sometimes the Pacific is screaming "warmth," but then the Polar Vortex falls apart. You’ve heard the term. It’s not a new storm; it’s a permanent feature of the high atmosphere. When it’s strong, it keeps the cold air locked in the Arctic. When it weakens or "stretches," that cold air spills south like a knocked-over bucket of ice water.

Predicting a Polar Vortex disruption more than three weeks out is nearly impossible. It’s the "wild card" that ruins many a seasonal outlook. You can have a forecast for a mild winter, and then one sudden stratospheric warming event sends Chicago into a -30 degree deep freeze for ten days. That’s not a failure of the forecast; it’s just the volatility of the system.

How the Pros Actually Build These Models

They use "ensembles."

Instead of running one model, agencies like the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) run dozens. Each one has slightly different starting conditions. If 45 out of 50 models show a warm signal for the Midwest in July, confidence goes up. If they’re all over the place? The forecast stays "Equal Chances."

"Equal Chances" is the meteorologist's way of saying "we have no clue, so expect anything." It’s the most honest answer in science, but people hate hearing it. We want certainty. We want to know if we need to buy a heavier coat or if the AC bill is going to ruin our summer budget.

📖 Related: Clayton County News: What Most People Get Wrong About the Gateway to the World

The Role of Climate Change in the Shift

It’s impossible to talk about a long term temp forecast without addressing the "loading of the dice."

Global warming doesn't mean every day is hot. It means the baseline has shifted. When meteorologists look at "normal" temperatures, they use 30-year averages. Currently, we use the 1991-2020 dataset. But even within that window, the last decade has been so much warmer that "normal" is a moving target.

This makes long-term forecasting even harder. The historical patterns (analogs) that forecasters used in the 70s and 80s don't always work anymore. The atmosphere is holding more moisture and more energy. This leads to "stuck" patterns where a heatwave doesn't just last three days—it sits on a region for three weeks.

Reading Between the Lines of the Maps

When you look at a seasonal outlook map and see a big orange blob over your state, it doesn't mean every day will be a scorcher. It’s all about probability.

A "60% chance of above-normal temperatures" means there is still a 40% chance it could be near normal or even cold. It’s a tilt of the odds. Think of it like a baseball player hitting .333. They are likely to get a hit, but they’re still going to strike out plenty of times.

I’ve seen people cancel trips because of a monthly forecast showing "below average" temps, only to have the one week they travel be the warmest week of the month. Don't do that. These forecasts are meant for large-scale planning—energy companies deciding how much natural gas to store, or state governments prepping for drought. They aren't meant for your backyard BBQ.

Regional Nuances You Should Know

The West Coast is dominated by the Pacific. If the "Ridges" are sticking near the coast, expect dry and warm.

👉 See also: Charlie Kirk Shooting Investigation: What Really Happened at UVU

The East Coast is a battleground. You have the Gulf Stream, the Appalachian terrain, and the influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation. It’s arguably the hardest place in the world to produce an accurate long term temp forecast because the variables change by the hour.

In the Plains, it’s all about the "low-level jet." That’s the river of air that pumps moisture from the Gulf of Mexico. If that jet is active, you get humidity and stormy nights. If it’s suppressed, the ground dries out, the sun bakes the soil, and you get a feedback loop of heat that’s incredibly hard to break.

Why 2026 is Looking Different

As we move deeper into this decade, we are seeing the emergence of "flash droughts" and "heat domes" that appear with very little warning. These aren't captured well in the 90-day outlooks. We are entering a period where the "long term" might actually be getting harder to predict, not easier, despite our better tech. The old rules are being rewritten in real-time.

Actionable Steps for Using Long-Term Data

If you’re trying to plan your life around these forecasts, here is the realistic way to do it:

- Check the CPC "Three-Month Outlook" but only look at the trends, not the specific numbers. If you see a consistent "Above Normal" signal for three months straight, start budgeting for higher cooling or heating costs.

- Watch the "Teleconnections." Keep an eye on the ENSO status. If we are moving into a strong La Niña, and you live in the South, expect a dry winter. This is a great time to tackle outdoor home repairs that require dry weather.

- Ignore the "Almanacs." Old Farmer’s Almanacs are fun for coffee table reading, but their secret formulas aren't based on modern fluid dynamics. Stick to NOAA, the ECMWF, or reputable private firms like AccuWeather or WeatherBell for actual data.

- Look for "Persistence." If the last three months have been record-warm, the odds favor the next month being warm too. The atmosphere has "memory" due to soil moisture and ocean temperatures. A dry, hot desert stays hot more easily than a lush forest.

- Diversify your sources. Don't just trust one app. Apps are often just a single model (usually the GFS or the Euro) translated into an icon. They don't have the human nuance that a discussion from a professional forecaster provides.

Forecasting is a bridge between what we know and what we hope for. We want to control the future, but the air above us is a chaotic, beautiful mess. Use the data as a guide, not a gospel. The best long term temp forecast is the one where you prepare for the trend but keep an umbrella in the car just in case the "butterfly" decides to flap its wings.

Pay attention to the local National Weather Service (NWS) offices. They often post "Area Forecast Discussions." These are technical, but they give you the why behind the forecast. When you see a meteorologist write "uncertainty remains high," that is your cue to keep your plans flexible. Betting everything on a 30-day map is a recipe for a ruined weekend. Stay informed, stay skeptical of "clickbait" snow maps, and remember that nature doesn't check the calendar before it decides to change its mind.