You've probably heard the claim before. People say the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is so massive that you can see it from the moon, or at least from a low-earth orbit satellite. It's a terrifying thought. A swirling continent of trash, twice the size of Texas, bobbing in the middle of the ocean like a neon sign of human failure.

It's also mostly wrong.

If you hopped on a SpaceX flight today and looked down at the North Pacific Gyre, you wouldn’t see a floating island of plastic. You'd see blue. Deep, endless, shimmering blue water.

This isn't to say the problem isn't real—it’s actually much worse than a simple "island" would be—but the great garbage patch from space looks nothing like the viral AI-generated images of trash heaps clogging the sea. Understanding why it’s "invisible" to the naked eye from orbit is the first step in actually grasping the scale of the plastic crisis.

The "Soup" vs. The "Island"

Most people imagine a solid mass. Like a landfill that just happened to sprout in the water.

In reality, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) describes it as more of a "peppery soup." Most of the plastic is microplastic. These are tiny shards, often smaller than a grain of rice, that have been weathered down by UV rays and salt water.

Satellites have a hard time with this.

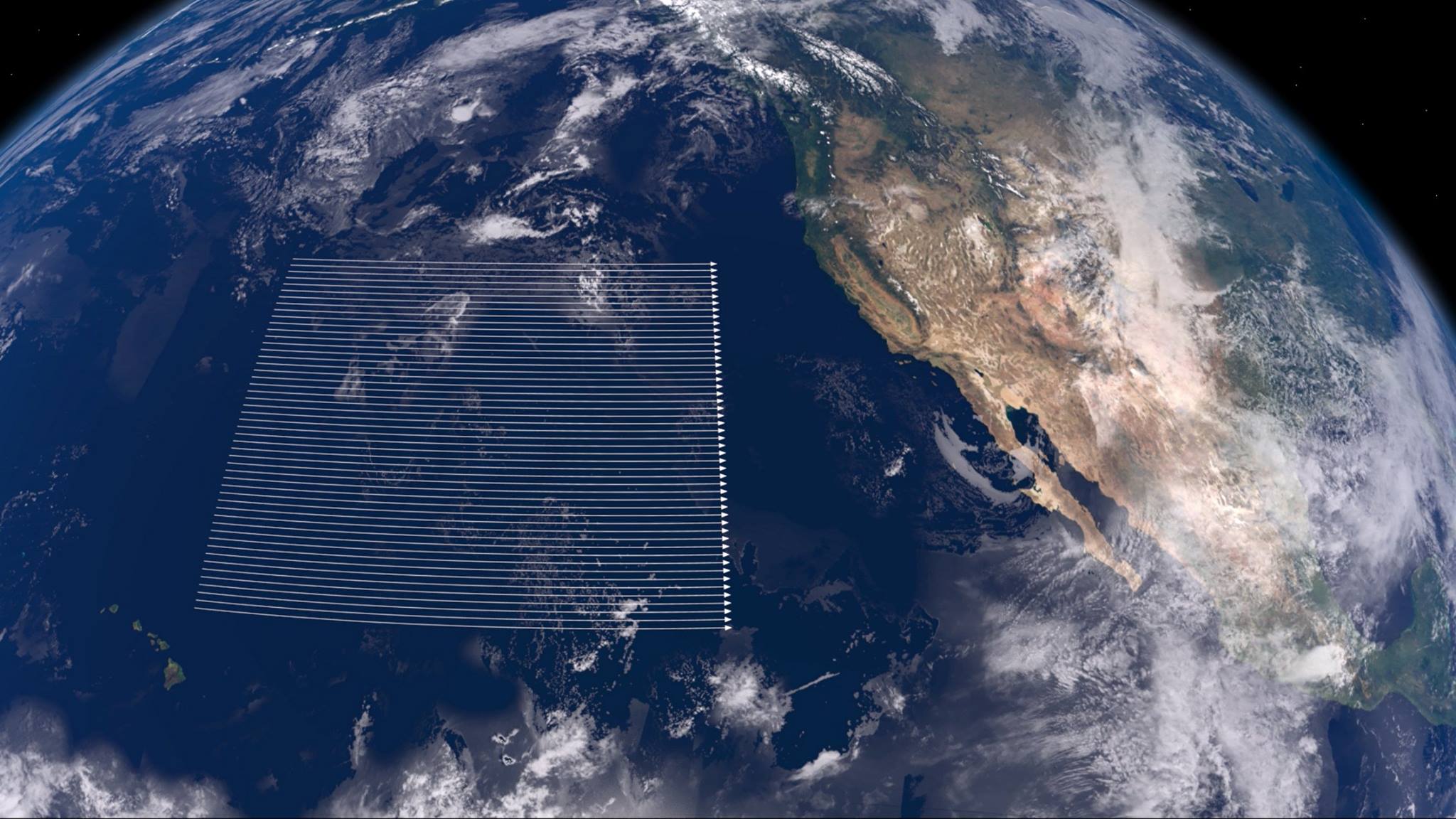

Standard optical cameras on satellites like Landsat or Sentinel-2 look for reflections. Water absorbs light in specific ways. Plastic does too. But when the plastic is suspended just below the surface or scattered across thousands of miles in tiny flecks, the "signal" gets lost in the "noise" of the waves.

Scientists like Dr. Laurent Lebreton, who has published extensively on the patch through The Ocean Cleanup, emphasize that the density is the issue. Even in the most concentrated areas, we’re talking about maybe 100 kilograms of plastic per square kilometer. To a satellite 400 miles up, that’s essentially invisible. It doesn't look like a solid object because it isn't one. It’s a dispersed nightmare.

How We Actually See the Great Garbage Patch From Space

We don't use regular cameras anymore. That's old school.

Instead, researchers are getting clever with remote sensing. Since we can't see the "trash" directly, we look for the "fingerprint" of the water.

One method involves multispectral imaging. By looking at specific wavelengths of light—specifically near-infrared—satellites can detect subtle changes in how the water reflects energy. Plastic reflects differently than seawater.

Then there’s the "glint" method.

Rougher water looks different than smooth water. Floating debris, even if it's small, can dampen the capillary waves on the ocean surface. It makes the water look slightly "oily" or smoother than it should be. Some researchers are using radar (SAR - Synthetic Aperture Radar) to detect these texture changes. It’s basically using space lasers to find where the ocean looks "too calm," which often points to a high concentration of gunk.

The European Space Agency's Role

The ESA has been at the forefront of this. They’ve been running projects like the "Remote Sensing of Marine Litter." They aren't looking for a giant rubber ducky from orbit. They’re looking for "proxies."

- They track ocean currents (gyres).

- They monitor sea surface temperature.

- They use AI to correlate satellite data with actual sightings from ships.

It’s a massive data puzzle.

Honestly, the term "patch" is kinda misleading. It makes it sound like you could walk on it. You can't. If you swam through the heart of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, you might see a few ghost nets or a wayward crate, but mostly, you’d just be swallowing a lot of tiny, invisible plastic bits.

Why the "Invisible" Problem is a Bigger Tech Challenge

Because you can't see the great garbage patch from space with a simple photo, it's incredibly hard to clean up.

Think about it. If it were a solid island, we’d just send a fleet of barges and scoop it up. Done.

But because it’s a soup, you have to filter it. And you can't just filter the whole ocean because you'd kill all the plankton and small fish—the very foundation of the food chain.

Technology is trying to bridge this gap. Organizations like The Ocean Cleanup use satellite-linked buoys. These buoys drift with the plastic, sending GPS coordinates back to base. This creates a "heat map" of where the trash is moving.

We’re also seeing the rise of hyperspectral imaging. This is the "big guns" of space tech. While a normal camera sees three colors (Red, Green, Blue), a hyperspectral sensor sees hundreds of narrow bands of light. This allows scientists to identify the type of plastic from space. Is it polyethylene? Polypropylene? This matters because different plastics behave differently in the current.

The Misconception of the "Trash Island"

We need to talk about those viral photos. You've seen them. A guy in a canoe in a sea of bottles.

Most of those photos are taken in river mouths or harbors after a heavy rain. They are not the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

The patch is in the "horse latitudes." It’s a high-pressure zone where the wind is often dead calm. It’s a desert in the middle of the ocean. The reason the trash stays there isn't because there's a barrier; it's because the North Pacific Gyre—a system of four currents—traps it in a circular motion.

📖 Related: Icon Alight Motion Logo PNG: Why Most Creators Use the Wrong Version

The debris doesn't just stay on the surface, either.

Heavier plastics sink. Over time, biofouling (when algae and barnacles grow on the plastic) makes even buoyant plastic heavy enough to drift down into the water column. This means the stuff we "see" from space is just the tip of the iceberg. There is a "vertical" garbage patch that extends hundreds of feet down.

New Frontiers in Orbital Detection

In the last couple of years, we've seen a shift toward using CubeSats.

These are tiny, cheap satellites about the size of a shoebox. Because they are cheap, we can launch hundreds of them. A "constellation" of CubeSats can provide near-constant coverage of the North Pacific.

This is huge.

Before, we had to rely on big, expensive government satellites that only passed over the patch every few weeks. Now, we can track the movement of plastic "fronts" in real-time.

Recent studies published in Scientific Reports have shown that we can now detect "macroplastics" (the big stuff like nets and buoys) with about 80% accuracy using these new satellite arrays. It’s a massive leap forward.

But let’s be real: we are still playing catch-up.

The amount of plastic entering the ocean is still outpacing our ability to track it, let alone remove it. Every year, roughly 8 million metric tons of plastic enter the sea. That’s like dumping a garbage truck into the ocean every single minute.

What This Means for the Future

If we can’t see the great garbage patch from space clearly yet, we are getting closer.

The next generation of satellites, like the PACE (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem) mission, will give us the most detailed look at the ocean's health ever recorded. It won't just show us where the plastic is; it will show us how that plastic is affecting the literal breath of the planet—the phytoplankton that produces half of the world's oxygen.

The complexity here is staggering. It’s not just a "trash problem." It’s a chemistry problem, a physics problem, and a data problem all rolled into one.

We’ve spent decades treating the ocean like a "get out of jail free" card for our waste. Now, we’re using the most advanced technology humanity has ever built—spacecraft—to try and find the mess we’ve hidden in plain sight.

👉 See also: Old VIN Number Search: Why Your 17-Digit Logic Won't Work on Classics

Actionable Steps and Insights

Understanding the reality of the garbage patch changes how we have to fight it. Since it's not a solid mass we can just go "grab," the focus has to shift to prevention and localized tech.

- Support Upstream Interception: The most effective "cleanup" happens in rivers. Once plastic reaches the open ocean and breaks down into the "soup" visible only to specialized satellites, the cost of removal skyrockets. Look into projects like the "Interceptor" which stops plastic in high-emission rivers.

- Acknowledge the Scale: Recognize that "recycling" isn't a silver bullet. Only about 9% of plastic ever made has been recycled. The goal should be "reduction," specifically of single-use plastics that are the primary components of the microplastic soup.

- Utilize Open Data: If you're a developer or data scientist, the ESA and NASA offer open-access satellite data. Global Fishing Watch and other platforms are increasingly using this to track marine debris.

- Consumer Choices Matter (But Policy Matters More): While choosing glass over plastic helps, pushing for extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws is what actually changes the landscape. This forces companies to be responsible for the entire lifecycle of their packaging.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch isn't a destination you can visit or a landmass you can map with a drone. It is a ghost. A pervasive, microscopic, and incredibly destructive ghost that haunts our oceans. Space technology is finally giving us the glasses we need to see it, but it’s up to us to do something with that vision.